Sacred Wells (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – NT 2741 7241

Also Known as:

- Wells o’ Weary

- Well of Wery

Archaeology & History

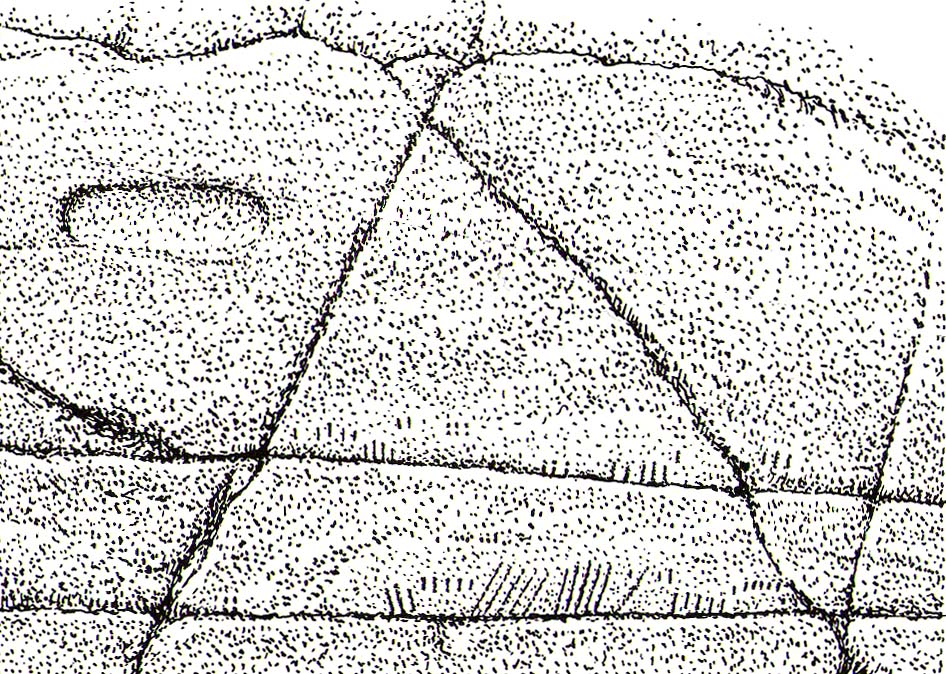

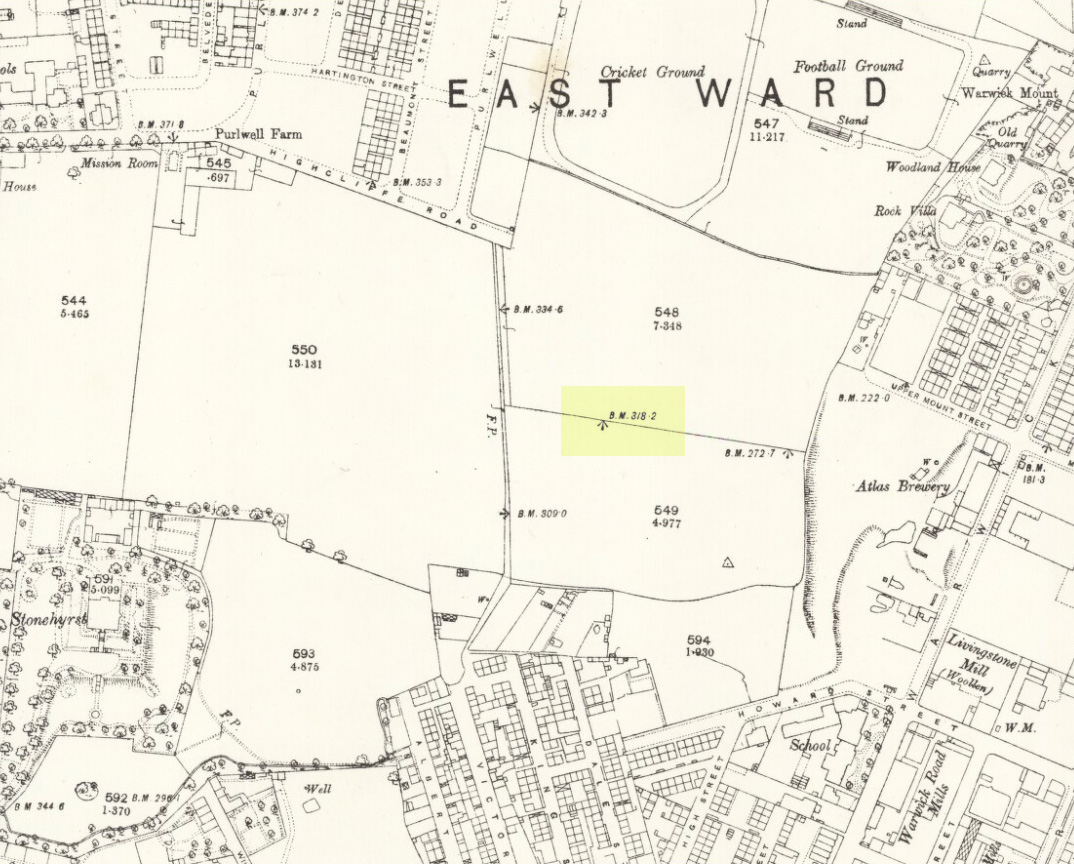

The precise spot for these “wells” is difficult to say today with any certainty, which is unfortunate as it was a renowned spot for a variety of reasons. The wells were apparently disrupted and fell back into the Earth when the Industrialists dug their train-line into the south-side of Arthur’s Seat. On the early maps, we can see several ‘troughs’, ‘pumps’ and ‘wells’—one or more of which are said to be the site (and which we base the OS grid-reference on, above).

The Wells of Wearie were one of nearly a dozen sacred and healing wells surrounding legendary Arthur’s Seat at the edge of Edinburgh, and whose waters were also said to have supernatural properties. Shown on James Kirkwood’s 1821 map of Edinburgh (left) as the ‘Well of Wery’, this curiously named site was renowned in earlier centuries as an excellent water supply for the local people — “to cure the weary traveller” for one. Today, all we have left of them are the small ponds immediately below the road, next to the converted railway line path, just as you come out of the long tunnel.

Folklore

In Henderson & Cowan’s (2007) fine work on Scottish fairy lore, they outline the witchcraft trial of a local woman, Janet Boyman, who was said to have performed ritual magick at the Wells of Wearie. They told:

“Jonet Boyman of Canongate, Edinburgh, accused in 1572 of witchcraft and diabolic incantation, the first Scottish trial for which a detailed indictment has so far been found. Indeed, it is one of the richest accounts hitherto uncovered for both fairy belief and charming, suggesting an intriguing tradition which associated, in some way, the fairies with the legendary King Arthur. At an ‘elrich well’ on the south side of Arthur’s Seat, Jonet uttered incantations and invocations of the ‘evill spreits quhome she callit upon for to come to show and declair’ what would happen to a sick man named Allan Anderson, her patient. She allegedly first conjured ‘ane grit blast’ like a whirlwind, and thereafter appeared the shape of a man who stood on the other side of the well, and interesting hint of liminality. She charged this conjured presence, in the name of the father, the son, King Arthur and Queen Elspeth, to cure Anderson. She then received elaborate instructions about washing the ill man’s shirt, which were communicated to Allan’s wife. That night the patient’s house shook in the midst of a huge and incomprehensible ruckus involving winds, horses and hammering, apparently because the man’s wife did not follow the instructions to the letter. On the following night the house was plagued by a mighty din again, caused, this time, by a great company of women.’”

The Wells were, in earlier centuries, a site where lovers and wanderers came to relax and dream. It was a traditional gathering spot — not just for witches! — and poetry was written of them – including this by A.A. Ritchie:

“The Wells o’ Wearie —

Sweetly shines the sun on auld Edinbro’ toun.

And mak’s her look young and cheerie;

Yet I maun awa’ to spend the afternoon

At the lanesome Wells o’ Wearie.

And you maun gang wi’ me, my winsome Mary Grieve,

There’s nought in the world to fear ye;

For I hae ask’d your minnie, and she has gien ye leave

To gang to the Wells o’ Wearie.

O the sun w-inna blink in thy bonny blue een.

Nor tinge the white brow o’ my dearie.

For I’ll shade a bower wi’ rashes lang and green,

By the lanesome Wells o’ Wearie.

But Mary, my love, beware ye dinna glower

At your form in the water sae clearly,

Or the fairy will change ye into a wee wee flower,

And you’ll grow by the Wells o’ Wearie.

Yestreen, as I wander’d there a’ alane,

I felt unco douf and drearie,

For wanting my Mary a’ around me was but pain

At the lanesome Wells o’ Wearie.

Let fortune or fame their minions deceive,

Let fate look gruesome and eerie ;

True glory and wealth are mine wi’ Mary Grieve,

When we meet by the Wells o’ Wearie.

Then gang wi’ me, my bonny Mary Grieve,

Nae danger will daur to come near ye.

For I hae ask’d your minnie, and she has gien ye leave

To gang to the Wells o’ Wearie.”

References:

- Baird, William, Annals of Duddingston and Portobello, Andrew Elliot: Edinburgh 1898.

- Bennett, Paul, Ancient and Holy Wells of Edinburgh, TNA: Alva 2017.

- Carrick, John D. (ed.), Whistle-Binkie, or the Piper of the Party – volume 2, David Robertson: Glasgow 1878.

- Colston, James, The Edinburgh and District Water Supply, Edinburgh 1890.

- Henderson, Lizanne & Cowan, Edward J., Scottish Fairy Belief: A History, John Donald: Edinburgh 2007.

- Ramsay, Alexander, On the Water Supply of Edinburgh, Neill & Co.: Edinburgh 1853.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.