Settlement: OS Grid Reference – SD 898 653

From Malham village, take the winding uphill road up Malham Rakes (not the Malham Cove road). If you aint sure, ask a local. Get to the top of the long winding road and, a mile on, you meet with another single-track road on the top level known as Street Gate. Stop here, then head across the grasslands on the left-side of the road, southwest. There are a couple of footpaths running over the land here: I wouldn’t say it makes much difference which one you take as they take you in the right direction. You’ll eventually meet the old craggy hilltop with the drystone walling down t’other side of it. You’re here!

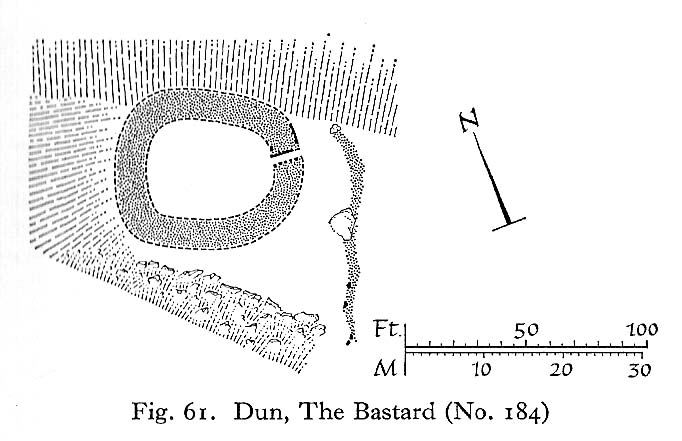

Archaeology & History

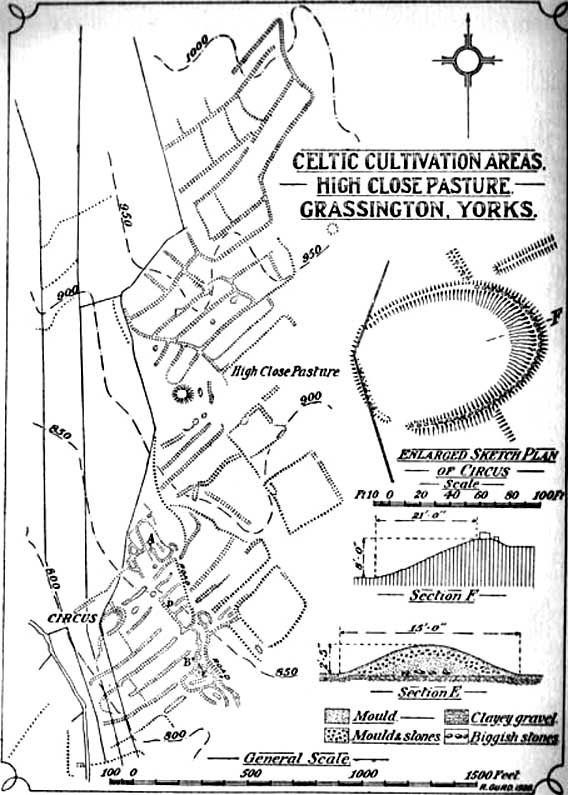

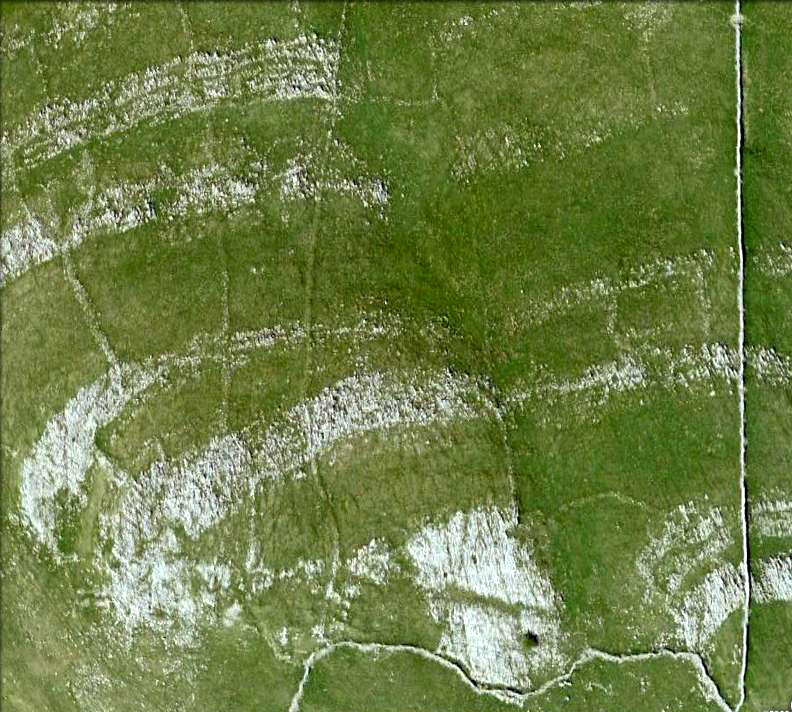

The history of this region seems to have been covered to a great deal by the likes of Arthur Raistrick and his mates, though I can’t find a specific entry in mi library about the remains we’re looking at here. Surrounding the edges of the small hill, as can be seen in the aerial photo here, walling has clearly been built up around it, with considerable remains still visible at ground level, as indicated in the photos aswell.

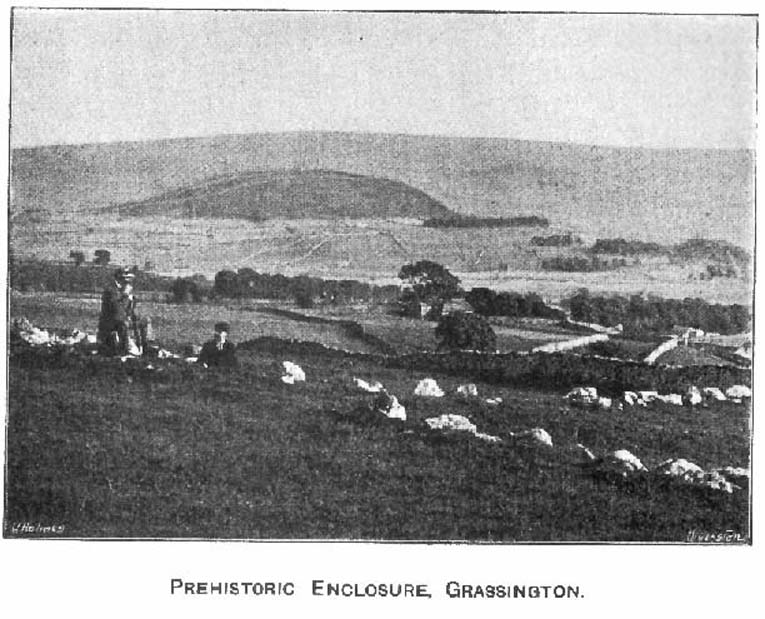

A settlement or large stone-walled enclosure, lying primarily on the north side of the drystone wall, measures approximately 82 yards north-to-south, and roughly 78 yards (72m) east-to-west, with a rough circumference around the outer edges of its rough elliptical outlines of more than 270 yards (250m). Along the walled edges can clearly be seen several ‘hut circle’ remains: one in particular at the northeastern side and, more prominently, at the southeastern side, are in reasonably good states of preservation. The northeasterly hut circle measures approximately six yards across. The stone walls of this circle are more than a yard wide. The ‘hut circle’ on the southeastern corner are more prominent and is in a better state of preservation, but much of the structure has of course been ruined to build the adjacent, more modern, drystone walls. This circular structure is larger than its counterpart on the northeast, measuring some 13 yards across.

The southern edge of the main settlement walling has been built up against and onto a large length of bedrock running roughly east-to-west. This inclusion of local geological features within man-made settlements and houses is a feature found all over Malham Moor and adjacent areas, for many miles around here. (see the Hammond Close settlement, for example) The southernmost section of the Torlery Edge settlement is in a reasonable state of preservation, as is the length of walling along its eastern edge. Along the northern section of the settlement it seems that an internal enclosure feature has been built (“perhaps for cattle?” would be the archaeologists usual query); whilst the western edges are the least visible part of this monument.

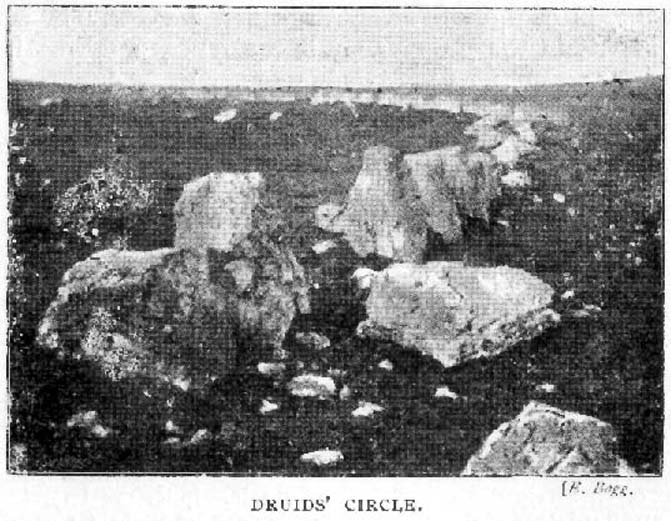

If we now jump over the drystone wall running along the southern edges (and visible in the aerial photo above), we can see a series of six, perhaps seven, hut circles, all adjoining each other and running along the line of the wall. Some of these are in a very good state of preservation and an excavation of these sites might prove fruitful. (unless it’s already been done – does anyone know?) Two of these hut circles have entrances clearly visible. They are all roughly the same size and structure, with average diameters (from outer wall to outer wall) of 7 yards. They consist of a rough ring of small upright stones, packed with smaller rocks and (in bygone times) peat and wood. Sheltered from the north winds by the ridge above it and the extensive ancient enclosure walling (not the drystone, which in itself is very old), this row of prehistoric buildings were probably for members of the same tribal group.

Without excavation it’s difficult to date these hut circles, but they would probably have been used between the Bronze Age and Romano-British period. There is every likelihood they were also used up to the medieval period, as this land was acquired (i.e. stolen) from local people by the Church and their law-bringers. We know that much of the landscape hereabouts was possessed by Fountains Abbey in the 12th century, who made extensive use of the area for their cattle; and we find considerable evidence scattering these hills of medieval archaeological remains.

Although the site is catalogued as a separate site from, say, the settlement remains and enclosures we find at Combe Hill, Prior Rakes, New Close, and other field areas close by, this individual archaeological site must be assessed as part of a greater collective series of settlement remains hereby. Instead of looking at this as an individual settlement, its relationship with the others in the vicinity needs re-evaluating and contextualizing and set within a wider and more realistic vision. Whilst appreciating that detailed modern excavations have yet to be done in this region on a scale that is required (as with many of our northern archaeological landscapes), it is probable that this singular settlement was part and parcel of what was once a prehistoric city.

If you visit this particular site, spend a few days looking round at the many other settlements and prehistoric religious sites in the area. And don’t forget to look and enquire as to why the Romans came and built a huge monument near the centre-edges of this domain of our prehistoric ancestors. Tis a fascinating arena indeed…

References:

- Dixon, John & Phillip, Journeys through Brigantia – volume 2: Walks in Ribblesdale, Malhamdale and Central Wharfedale, Aussteiger: Barnoldswick 1990.

- Raistrick, Arthur & Holmes, Paul F., Archaeology of Malham Moor, Headley Bros: London 1961.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian