Stone Circle: OS Grid Reference – SD 9647 3355

The site is usually invisible, being under the waters of Walshaw Dean Middle Reservoir. But in good droughts you can catch a glimpse of the place. So take the Widdop road as it’s known locally, from either Hebden Bridge up past Heptonstall, or from Burnley, Nelson & Colne side, and park-up by the pub a few hundred yards east of Widdop Reservoir. Walk a few hundred yards back down the road (east) and take the dirt-track on the other side of the road on the Calder-Aire link leading to the Pennine Way. Walk up past the first reservoir, keeping to its west-side, until you reach the Lodge house where the second lake appears. Now, if the water’s down, walk along its western-edge for about 50 yards, looking into the dried flat ahead of you and you’ll see the loose ring of small stones. That’s it! Or as Mr Roth described the place in 1906, “The position of the circle is on the left-hand side of the valley going up, a few yards above the dam of the second reservoir.”

Archaeology & History

This is a somewhat bizarre archaeological site, whose nature we may never fully recover. Although listed and scheduled as a plain stone circle by Aubrey Burl (2000) and others, both the placement and structure of the site implies a more funerary aspect to it. This was suggested by Ling Roth (1906) when he first wrote about it. But for me, the position of the site in the landscape calls into question the archetypal ‘stone circle’ category, as it is somewhat hemmed-in both east and west, with limited views north, and only a good view of open lands to the south (summer). It’s just a bit odd when compared to other megalithic rings in the Pennines. But perhaps this ‘privacy’ was intended — as there is only scattered evidence of other human activity in this valley and on the moors above. Perhaps this site was meant to be ‘cut off’ from the rest of the world. We might never know…

There is also the peculiar addition inside this stone circle of an arc of walling facing southeast, which is unique in this part of Britain. But this walling seems to have been a later addition and has the hallmarks of being some small shelter, or even an early grouse-shooting butt (there’s tons of game-birds here, and this would be an excellent spot to shoot from) This internal wall may have been constructed from stone that came from the circle itself: perhaps in a rubble wall, perhaps an internal cairn. It seems likely. Mr H. Ling Roth (1906) also mentions this feature in what was the first description of the site, where he told:

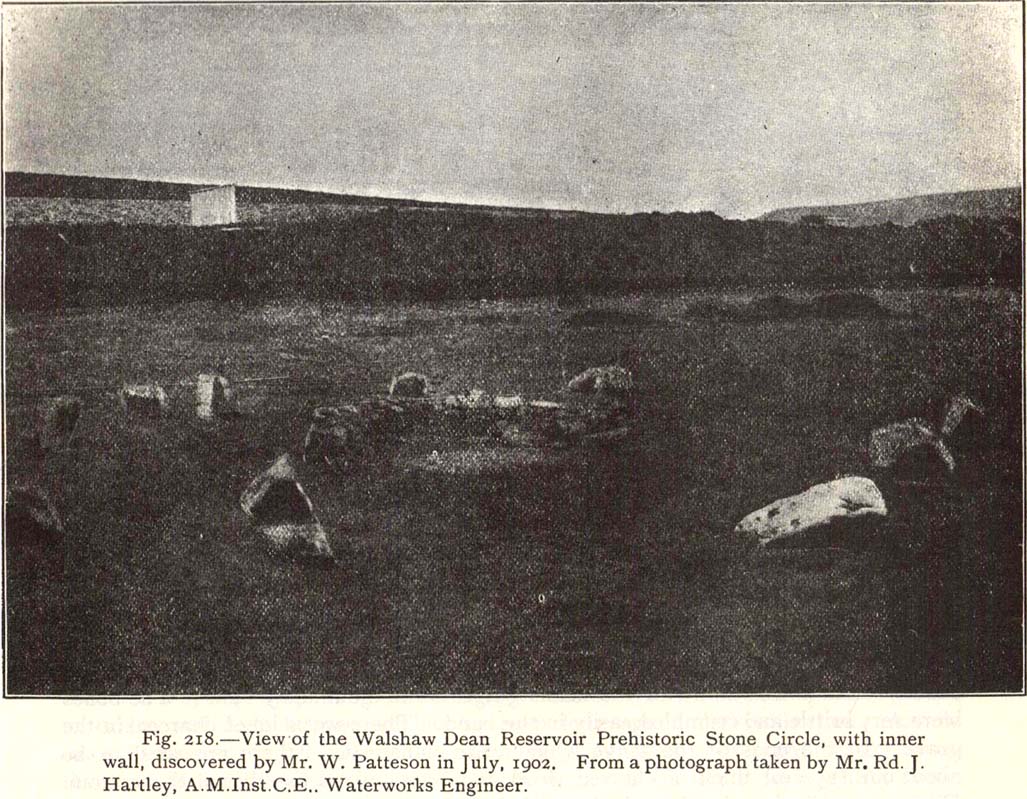

“The stone circle at Walshaw Dean Reservoir…was discovered by Mr W. Patteson, the resident engineer, in July 1902. The circle consists of ten irregular stones apparently local rock, varying considerably in size, one measured 6ft 3in (1.9m) long and stood about 30 inches (76cm) above the clay when the peat surface was removed. Whether the stones are deeply embedded has not been ascertained, but where they were covered by the peat a clear white band is apparent. The circle is 36 feet (11 metres) is diameter and of very fair exactitude. Inside the circle as shewn on the plan and in the view there was a rouhg carved wall which measured across the ends 12ft (3.7m). The wall had been partly pulled down and reset immediately before examination by a party of visitors soon after the discovery. Its presence in the circle may be fortuitous, but after the two unsystematic disturbances to which the ground had been subjected, it is not possible to form an opinion about it. That something had been buried in the centre of the circle is probable when we bear in mind the circumstances of stone circles elsewhere, but an examination shewed only that the ground had been disturbed and Mr Patteson explained to me that such disturbance was not of recent date.”

To my knowledge, no subsequent excavation of the site has ever been done, but it would appear that the waters have washed part of the site away and any remains that may once have been found within the ring have been discarded by more than a century of erosion. Traces of small walled structures have also been noted close to the circle in recent years, suggestive of settlement remains. On a TNA outing last year, we also found previously unrecorded prehistoric remains on this hills above here. When Geoffrey Watson (1952) wrote his survey on prehistoric Calderdale, he suggested that the Walshaw Circle may have been placed alongside the branch of an early trade route running along the northern edge of the valley. Not so sure misself…

References:

- Bennett, Paul, The Old Stones of Elmet, Capall Bann: Milverton 2001.

- Burl, Aubrey, The Stone Circles of Britain, Ireland and Brittany, Yale University Press 2000.

- Roth, H. Ling, The Yorkshire Coiners, 1767-1783; and Notes on Old and Prehistoric Halifax, F.King: Halifax 1906.

- Watson, Geoffrey G., Early Man in the Halifax District, HSS: Halifax 1952.

Links:

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.