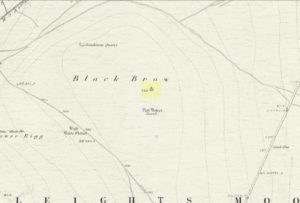

Cairn: OS Grid Reference – SD 8994 6405

Also Known as:

- Friar’s Heap

- Monk’s Grave

There’s nowhere to park any vehicles anywhere near this place if you wanna reach this site. And so, from Malham village, take steep eastern road up Malham Rakes (ask a local if needs be) for exaclt half-a-mile (0.81 km) where, at a bittova sharp turn in the road, there’s a footpath on your left. Walk along here for about 350 yards until you hit a straight line of walling on your left. Follow this along, about 30 yards before it turns at a right-angle. On the other side of the wall from here, a barely discernible denuded heap is in the overgrown field. That’s it!

Archaeology & History

To be found above the grand rise of Malham Cove—on its eastern side—the earliest mention I’ve found of this once-large prehistoric burial cairn was in the Cravendale travelogue of William Howson (1850). His description was only a brief one, telling us how,

“The workmen engaged on the fences have lately opened a large barrow, which is known by the local as the Friars’ Heap, near the eastern arm of the Cove, and a quantity of human bones were found.”

In Howson’s opinion he thought “the spot is much more likely to be connected with the marauding Scots than the peaceful monks”; but he was wrong on both counts. When the site was later visited and described by the great northern antiquarian, Harry Speight – aka, Johnnie Gray (1891) – he told us that the place “was much more likely to have been a British or Danish burial mound.”

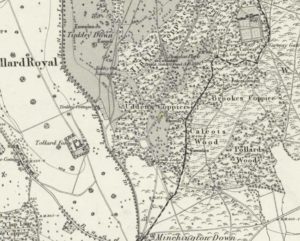

Originally standing to a height of more than six-feet, the tomb has subsequently been reduced to half that height. The most lengthy descriptions of it were written by the regional antiquarian Arthur Raistrick. In his topographical literary meanderings across the Malham landscape, he gives a fine overview of its features and locale:

“Across the clints the old valley which leads to the edge of the Cove is seen, and looking upstream a grand impression of the Dry Valley, properly called Watlowes, is obtained. Across the foot of the valley a stile crosses rhe wall, and a footpath goes up the hill near to the boundary wall of the Cove; this is Sheriff Hill. At the prominent corner of the wall where the path resumes a level course, it joins the path from Malham Lings called Trougate. Between here and the road there are abundant traces of the Celtic fields, nestling under the small limestone crags that offer shelter from the northeast, evidently as unwelcome a quarter for the wind when these were occupied as today. Where the wall turns at right-angles again towards the Cove, there is a very prominent circular mound nearly a hundred feet in diameter. This is a burial mound of late Iron Age. It was dug into about the year 1845 and in addition to many human bones , fragments of an iron spearhead were found. It is to be regretted that no careful account of this excavation was preserved, as there seems no doubt that this was a multiple burial of some importance. Like other burial mounds in this district, the site was well chosen with a most extensive view which includes many notable hill summits…”

This latter remark could well have come from the pen of the old ley-hunter, Alfred Watkins (1925), who noted time and again how landscape features would seemingly connect one site with another, and another. (the modern idea of leys as ‘energy-lines’ is an American invention and wholly without merit)

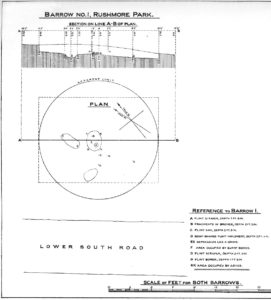

A few years after Raistrick gave us his initial description, the cairn was excavated. In his short work on the archaeology of Malham Moor (1961), he wrote:

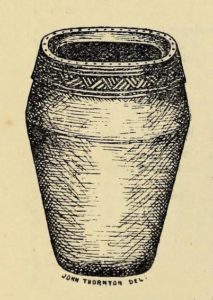

“A burial mound (that was) three-quarters removed at the time of the enclosures (about 1845) when the mound was dug as a quarry for walling stones. The remaining fragment was trenched right through and was found to be built entirely of stone with a kerb of large flaggy stone laid on the slope at the foot of the mound. Many fragments of decorated pottery were founmd under the turf cover and were associated with what appeared to be discarded gravel from the original quarrying, so may have come from the centre. At the inner edge of the kerb and under a carefully placed cover-stone, a smal oval vessel was got. This is of thick bluey-grey paste, red outside and very flaky so that part of the surface is lost on the two-thirds of the vessel which remains. Prof Stuart Piggott has reported on the pottery. Of this vessel he says — “an oval cup of the so-called ‘Incense Cup’ class: one sherd is of the wall and base of one end, the other a piece spalled off from the inside of the base. I only know of one paralle to this remarkable pot, another oval incense-cup from Far Fields, Lockton, N.R. Yorks, in the York Museum. A very odd little oval ‘cup’ of sandstone from Defford, Bredon, Worcs, in the Hastings Muesum at Worcerster is a stray find and might be of any age, and anyway only provides a vague parallel.”

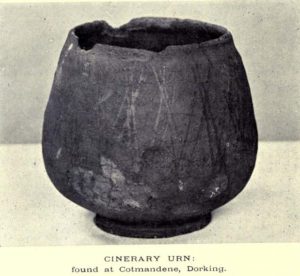

Another “vessel is represented by sherd of what appears to be a small cinerary urn of collared or overhanging-rim type with the yellow-brown surface characteristic of so many pots of this class. The decoration appears to be in alternating panels of vertical and horizontal lines of uncertain width, the whole forming the so-called ‘hurdle’ pattern. The ornament is made of double lines of twisted cord, one with a right-hand and the other with a left-and twist: such ornament is widely distributed on such vessels…

“A third “vessel is represented by a few sherds with purple-red exterior, decorated with impressed cord, whipped cord and grooving. It is diffcitul to say what sort of pot is represented, but I suspect something within the food vessel class… The whole assemblage could well be contemporary and would fall withini the Middle Bronze Age of conventional nomenclature, somwhat in the middle of the second millenium BC…”

The most striking feature of this site is its position in the landscape, typical of large cairns in the Pennines and much further afield. The view to the south is extensive and would have had some bearing on its construction, as such heights allow for the spirits of the dead to move across the landscape. The huge cliffs of Malham Cove below may also have been an important factor. In the days when this tomb was built, a great waterfall existed at the Cove that has subsequently fallen back to Earth. In many traditional cultures, water is an extremely important element. Its relationship to life is obvious; but also in the Lands of the Dead water feeds the spirit on its journeys. These animistic and geomantic features are essential in looking at the nature of the placement of sites—and this at Sheriff Hill would have been no exception.

Enjoy your sojourns and meditations here…

References:

- Gray, Johnnie, Airedale, from Goole to Malham, 1891.

- Howson, William, An Illustrated Guide to the Curiosities of Craven, Whittaker: London 1850.

- Raistrick, Arthur, Malham and Malham Moor, Dalesman: Clapham 1947.

- Raistrick, Arthur & Holmes, Paul F., Archaeology of Malham Moor, Headley Bros: London 1961.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian