Cists (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – NN 7247 0188

Also Known as:

Archaeology & History

Somewhere in the woodland park, before the area was “ruined”, as Moray Mackay (1984) put it, by “sand and gravel workings”, and within 100 yards of the re-positioned Trysting Stone, there once remained the ruins of ancient tombs—probably neolithic or Bronze Age in nature. The ‘cists’ as they’re known (stone-lined graves), were described in several short articles at the beginning of the 20th century, shortly after their rediscovery. Drawing upon the initial article by Joseph Anderson (1902) in the Scottish Antiquaries journal, W.B. Cook (1904) wrote:

“The doubling of the (railway) line from Dunblane to Callander has necessitated the altering of a road at the Crofts, Doune, and on Tuesday, 8 May, while digging, the navvies came across two stone cists containing bones. The cists were made of stone slabs. On Thursday, the men came on another cist about five feet from the surface. It was 3 feet long and 2½ feet broad, composed of round stones, and a quantity of bones were found in it, and also an urn. Unfortunately a cart-wheel passed over the urn, smashing it. The pieces were, however, carefully collected and cemented and they are now in the possession of Mr Smith, Clerk of Works to the Caledonian Railway Company, Doune. One of the cists first found was quite empty, but the other contained a large number of human bones, the largest about 1½ inches long. The coffins were about 15 inches from the surface, and lay from east to west. They measured 2 feet 9 inches in length, and in breadth and depth about 18 inches. They are constructed of local stone, and near the spot there has been a dyke running from the burgh to the sand holes, as the foundation was visible when the soil was being removed. Some of the stones indicate that a house might have stood near the spot, but there had been no public burying-place nearer than at Kilmadock and at the little chapel of Inverardoch previous to 1784.”

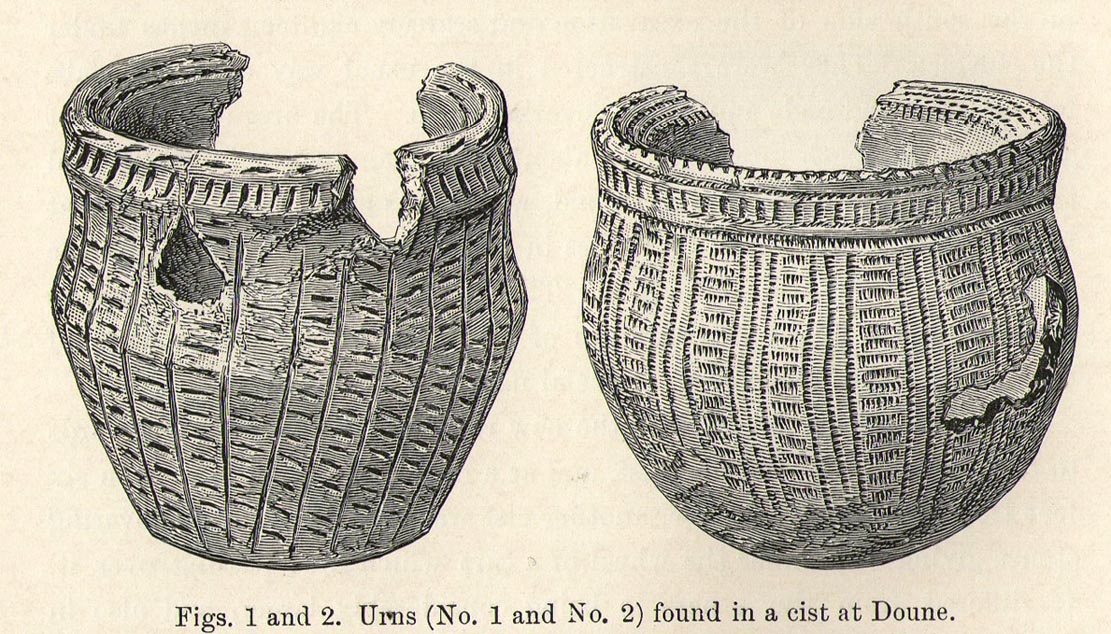

In Mr Joseph’s (1902) article, he told us there wasn’t one, but two urns which, after some considerable effort, were reconstructed. I’m not a great lover of urns misself, although when found in conjunction with the dead, we must ask, what was in them (if anything) when they were placed with the deceased? Food? Herbal beverages? Shamanic potions? In this case, we don’t know; and so all we are left with is Mr Anderson’s description of them:

“Urn No.1 is of the usual type of the so-called ‘food-vessel’, 4¾ inches in height by 5 inches in diameter at the mouth, the lip slightly bevelled inward, and the whole exterior surface ornamented. The ornamentation consists entirely of lines impressed into the soft clay with what seems to have been the roughly broken end of a small twig about ⅛-inch in diameter. On the level of the lip there are two parallel lines of short scorings going completely round the upper surface. On the exterior surface there is a kind of slightly concave collar half an inch in width immediately under the brim, which is ornamented with short perpendicular indentations about a quarter of an inch apart. Underneath the collar the vessel expands slightly to the shoulder and then contracts to a flattened base of three inches in diameter. The part above the shoulder is slightly concave externally, but the scheme of decoration above and below the shoulder is the same, consisting of a series of short impressed lines scarcely half an inch in length ranged round the circumference in horizontal rows about a quarter of an inch apart, and crossed perpendicularly by lines about half an inch apart, not impressed, but scored into the clay. The perpendicular lines above the shoulder are more divergent than those below the shoulder, which converge towards the bottom in consequence of the tapering form of the lower part of the vessel. The paste is coarse, and mixed with small stones; the wall of the vessel is about a quarter of an inch thick, and the colour a reddish brown on both the exterior and interior surfaces, but quite black in the fractures exposing a section of its thickness.

“Urn No.2 is of the same wide-mouthed, thick-lipped form of the so-called food vessel type, 5 inches high and 5½- inches in diameter at the mouth. The lip is bevelled inwards, and the general shape of the vessel somewhat resembles that of No. 1, except in the lower part, which, instead of tapering to a flat bottom, narrows from the shoulder in a much more gradual curvature to the bottom. The ornamentation also is much more elaborate, though partaking of the same general character, inasmuch as it is a scheme of impressed markings, in bands arranged alternately in vertical and horizontal directions and covering the whole exterior surface of the vessel. On the bevel of the rim is a horizontal band of three lines of impressed markings, surmounted on the upper verge of the rim by a row of shallow oval impressions less than ⅛ of an inch apart. Under this there is a horizontal band of impressed markings as with the teeth of a comb, and below that the general scheme of ornament is carried out in alternate bands of about half an inch in width, running vertically from collar to base. The one set of these bands consists of three parallel rows of impressions of about ⅛ of an inch in width, and ⅛ of an inch apart, which seem to have been produced in the surface of the soft clay by a comb-like instrument, while the other set of bands has been produced by marking the spaces between the triple bands in the same way with a similar instrument, but placing the lines horizontally and closer together.”

A short distance from here, more cists were found. It’s possible that a prehistoric graveyard this way lay, countless centuries ago…

Folklore

Moray Mackay (1984) reports that the Doune fairs used to be held here.

References:

- Anderson, Joseph, “Notices of Cists Discovered in a Cairn at Cairnhill, Parish of Monquhitter, Aberdeenshire; and at Doune, Perthshire,” in Proceedings Society of Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 36, 1902.

- Cook, W.B. (ed.), “Antiquarian Find at Doune,” in Stirling Antiquary, volume 3, 1904.

- Mackay, Moray S., Doune Historical Notes, Forth Naturalist & Historian: Stirling 1984.

- Royal Commission Ancient & Historical Monuments, Scotland, Archaeological Sites and Monuments of Stirling District, Central Region, Edinburgh 1979.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian