Standing Stone: OS Grid Reference – NS 80604 96871

Also Known as:

- Airthrey Castle West

- Canmore ID 47166

Not too troublesome to locate really… It’s at the top-end of the University, just above the side of the small Hermitage Road, about 100 yards along. Keep your eyes peeled to your left!

Archaeology & History

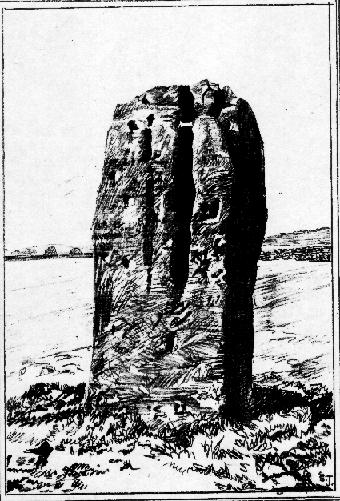

Today standing proud and upright, this ruinous standing stone has been knocked about in the last couple of hundred years. Although we can clearly see that it’s been “fixed” in its present condition, standing more than 10 feet high, when the Royal Commission lads came here in August 1952 (as they reported in their utterly spiffing Stirlingshire (1963) inventory), it wasn’t quite as healthy back. They reported:

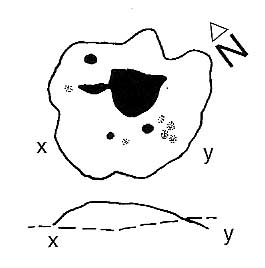

“Many years ago the stone, which is of dark grey dolerite, fell down and was broken, and the basal portion, now re-erected, is only 3ft 10in high; two large fragments however, still lie beside the base, and the original stone is said to have stood to a height of 9ft 4in. Of a more or less oblong section throughout, the re-erected stones measures 2ft 10in by 1ft 10in at ground level, swells to its greatest dimensions (3ft 2 in by 1ft 9in) at a height of 1ft 4in, and diminishes at the top…”

But the scenario got even worse, cos after the Royal Commission boys had measured it up and did their report, it was completely removed! Thankfully, following pressure from themselves and the help of the usual locals, the stone was stood back upright in the position we can see it today. And — fingers crossed — long may it stay here!

Folklore

A plaque that accompanies the monolith tells that the old village of Pathfoot itself was actually “built around this standing stone” — which sounds more like it was the ‘centre’ or focus of the old place. An omphalos perhaps? The additional piece of lore described in Menzies (1905) work, that an annual cattle fair was held here, indicates it as an ancient site of trade, as well as a possible gathering stone: folklore that we find is attributed to another standing stone nearby.

References:

- Fergusson, R. Menzies, Logie: A Parish History – volume 1, Alexander Gardner: Paisley 1905.

- Hutchinson, A.F., “The Standing Stones of Stirling District,” in The Stirling Antiquary, volume 1, 1893.

- Hutchinson, A.F., “The Standing Stones and other Rude Monuments of Stirling District,” in Transactions of the Stirling Natural History and Antiquarian Society, 1893.

- Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland, Stirlingshire – volume 1, HMSO: Edinburgh 1963.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian