Sacred Rocks: OS Grid Reference – SD 93329 26737

Follow the same directions to find the Blackheath Circle, but instead of turning onto the golf course, keep going up the steep road until you reach the T-junction at the top; then turn left and go along the road for about 200 yards, past the second track on the left, keeping your eyes peeled across the small moorland to your left where you can see the rocks rising up. Walk along the footpath towards them. You can’t really miss the place!

Archaeology & History

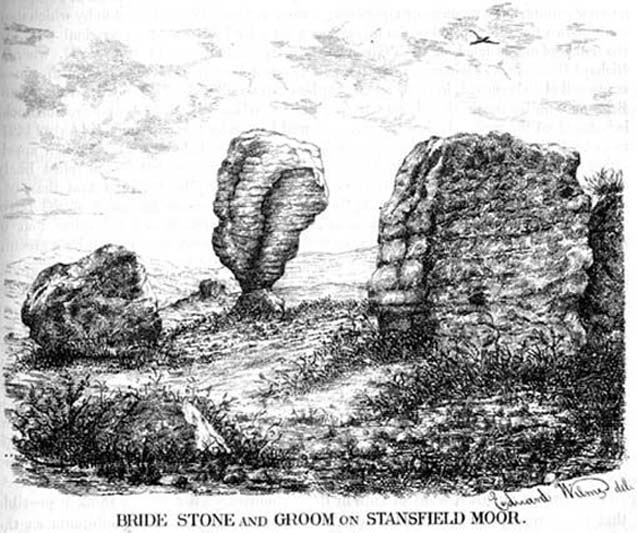

If you’re a heathen or geologist and you aint seen this place, check it out – you won’t be disappointed! First mentioned in 1491, this has always been a place of some repute. Its legendary companion, the ‘Groom’, lays resting on the Earth after being felled sometime in the 17th century.

A beautiful, remarkable and powerful site of obvious veneration. First described in local deeds as early as 1491, there are a great number of severely weathered boulders all round here, many like frozen rock giants haunting a magickal landscape. The modern lore ascribes the stones to be dedicated to Bride, goddess of the Brigantian people. And like Her legendary triple-aspect, we find here in the landscape a triple aspect to the outcrops themselves: to the west are the Bride Stones; to the east, the Little Bride Stones; with the Great Bride Stones as the central group, surveying everything around here.

At the main complex is what is singularly known as the Bride itself: a great smooth upright pillar of stone fourteen feet tall and nine feet wide at the top, yet only about two feet wide near its base, seemingly defying natural law. Watson (1775) described, next to the Bride herself, “stood another large stone, called the Groom…(which) has been thrown down by the country people” – probably under order of the Church. Crossland (1902) told how the Bride also acquired the title, “T’ Bottle Neck,” because of the stone’s simulacrum of an upturned bottle.

Scattered across the tops of the many rocks hereby are many “druid basins” as Harland and Wilkinson (1882) described them. Many of these are simply basins eroded over the millenia by the natural elements of wind and rain. It is possible that some of these basins were carved out by human hands, but it’s nigh on impossible to say for sure those that were and those that were not. If we could find a ring around at least one of them, it would help — but in all our searches all round here, we’ve yet to locate one complete cup-and-ring. So we must remain sceptical.

On the mundane etymological side of things, the excellent tract by F.A. Leyland (c.1867) suggested the Bride Stones actually had nothing to do with any goddess or heathenism, but derived simply from,

“the Anglo-Saxon adjective Βñáð, signifying broad, large, vast — hence the name of the three groups known as the Bride Stones. The name of The Groom, conferred on the prostrate remains, appears to have been suggested by the fanciful definition of the Saxon Brád, as given by (Watson).”

However, the modern place-name authority A.H. Smith (1963:3:174) says very simply that the name derives from “bryd, a bride.”

A “rude stone” was described in one tract as being a short distance below this great rock outcrop; it was turned into a cross by the local christian fanatics and moved a few hundred yards west, to a site that is now shown on modern OS-maps as the Mount Cross.

Folklore

Although local history records are silent over the ritual nature of these outcrops, tradition and folklore cited by the antiquarian Reverend John Watson (1775) tell them as a place of pagan worship. People were said to have married here, although whether such lore evolved from a misrepresentation of the title, Bride, is unsure. In the present day though there have been a number of people who have married here in recent years.

If the Brigantian goddess was venerated here, the date of the most active festivities would have been February 1-2, or Old Wives Feast day as it was known in the north. The modern witches Janet and Stewart Farrar, who wrote extensively about this deity (1987), said of Bride: “one is really speaking of the primordial Celtic Great Mother Herself,” i.e., the Earth Mother.

Telling of further lore, Watson said that weddings performed here in ages past stuck to an age-old tradition:

“during the ceremony, the groom stood by one of these pillars, and the bride by the other, the priests having their stations by the adjoining stones, the largest perhaps being appropriated to the arch-druid.”

New Age author Monica Sjoo felt the place “to have a special and uncanny power.” This almost understates the place: it is truly primal and possesses the virtues of strength, energy, birth and solace.

References:

- Bennett, Paul, The Old Stones of Elmet, Capall Bann: Milverton 2001.

- Crossland, Charles, “Place-Names in the Parish of Halifax in Relation to Surrounding Natural Features,” in Halifax Naturalist, volume 7, 1902.

- Farrar, Janet & Stewart, The Witches’ Goddess, Hale: London 1987.

- Harland, John & Wilkinson, T.T., Lancashire Folklore, John Heywood: Manchester 1882.

- Leyland, F.A., The History and Antiquities of the Parish of Halifax, by the Reverend John Watson, M.A., R.Leyland: Halifax n.d. (c.1867).

- Smith, A.H., The Place-Names of the West Riding of Yorkshire – volume 3, Cambridge University Press 1963.

- Watson, John, The History and Antiquities of the Parish of Halifax, T. Lowndes: London 1775.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian