Cairn: OS Grid Reference – SU 1305 7052

From the Avebury stone circle, walk out eastwards and straight up the ancient Ridgeway for about a mile until it levels out and meets up with the adjoining track upon the hilltop. Instead of going left or right, go straight across and onto the footpath that crosses Overton Down, until you reach the wide horse-racing track lookalike called ‘the Gallops.’ Stop – don’t go on it – and follow the fence down for a coupla hundred yards till you’ll see the fenced-off rise with a modern ‘barrow’ enclosed within. You’re very close! From here, go another 100 yards or so down and keep your eyes on the rise of land with rocks scattered around it. That’s it!

Archaeology & History

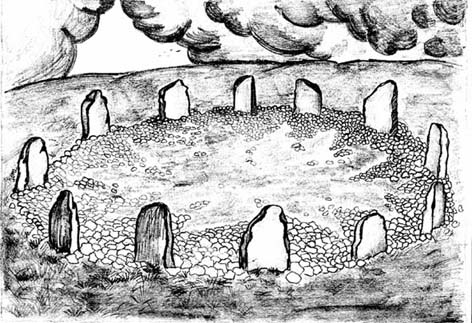

From all accounts, there’s been nowt of any consequence written about this site — which is bloody incredible to be honest!! We came here on a fine day (that’s Mikki, Geoff and June) in the company of the local Avebury magus, Pete Glastonbury. Crossing Overton Down towards an experimental “barrow” that some archaeo’s have knocked-up, the rise in the land here stands out quite clearly, saying (at the very least), “look at me!” But until Pete Fowler (2000) first described this “unrecorded kerbed round barrow” a few years back, it had escaped the noses of all previous archaeological surveys! How!?

What the hell do archaeologists in the Avebury area do with themselves if they can’t pick this sorta monument out!? But anyway…

This is quite a large rounded cairn structure by the look of it. At least 30-feet across, probably kerbed from the initial look (only for a few minutes, sadly). Local writer Terence Meaden has apparently found the site of some importance in his studies (not yet published). Its position here in the landscape was what caught my attention more than anything: it stands on the crest of the hill and has superb uninterrupted views far across the Avebury landscape. This siting was obviously quite deliberate. Less than 100 yards due north of here are two curiously placed stones which may ‘frame’ the cairn for a southern lunar alignment. I had no time to look at this really, so it would be good if some local Avebury dood could check this out. The outlying stones may be merely fortuitous, but it’d be good to know for sure!

The site has been plotted amidst a mass of landscape changes dating from the neolithic to medieval periods. It seems probable, on first impression, that the ‘cairn’ is of Bronze Age in character (though could be earlier), but until detailed analysis has been made we obviously won’t know for sure. A short distance to the south we have the much-denuded Overton Down site X1: another Bronze Age burial that yielded three beaker graves when Fowler excavated the place in the 1960s.

For those of you into geomancy, meditation and the subjective realms of genius loci, this one really grabbed me. Give it a go and lemme know what you get. But please, no stupid pagan or New Age offerings — the site doesn’t need that sorta thing.

References:

- Fowler, Peter, Landscape Plotted and Pierced: Landscape History and Local Archaeology in Fyfield and Overton, Wiltshire, Society of Antiquaries: London 2000.

* Pete Glastonbury is a Wiltshire-based photographer specialising in Landscapes, Astronomy, Archaeology, Infra-Red, Experimental Digital Photography and High Dynamic Range Panoramic photography.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian