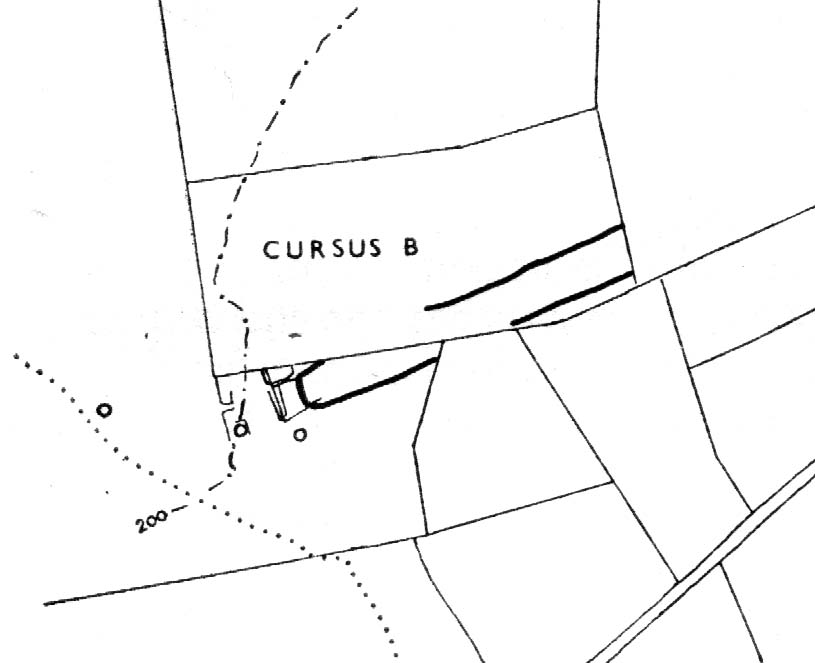

Tumulus: OS Grid Reference – NS 79616 98191

Also Known as:

- Ben Rhi

- Canmore ID 45986

- Fairy Knowe of Pendreich

- Hill of Airthrey

- King’s Hill

Various ways to get here. Probably the easiest is via the golf course itself, walking up towards the top where the trees reach the hills, but keeping your eyes peeled for the large archetypal tumulus or fairy mound near the top of the slope. Alternatively, come up through the wooded slopes from Bridge of Allan and onto the golf course, keeping your eyes ready for the self same mound sat in the corner by the walls. You can’t really miss it to be honest!

Archaeology & History

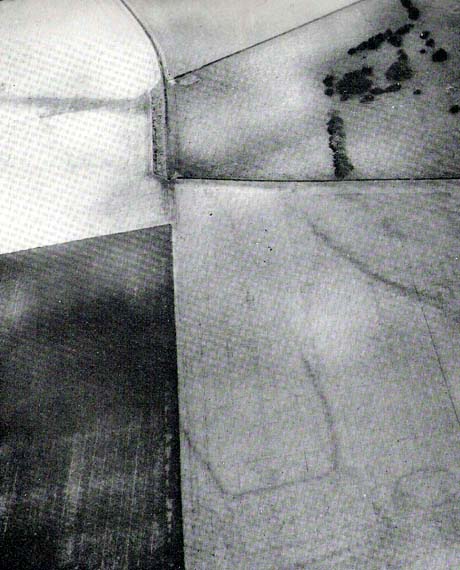

This is an impressive-looking burial mound sat, intact, on the edge of those painful golf courses that keep growing over our landscape — and you can see for miles from here! It would seem to have been placed with quite deliberate views across the landscape, reaching for countless miles into the Grampian mountains north and west across the moors of Gargunnock and Flanders towards Lomond and beyond…

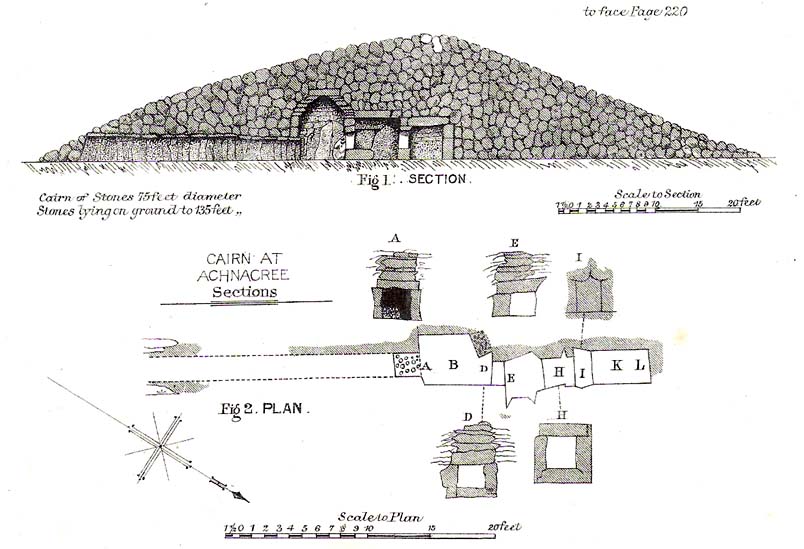

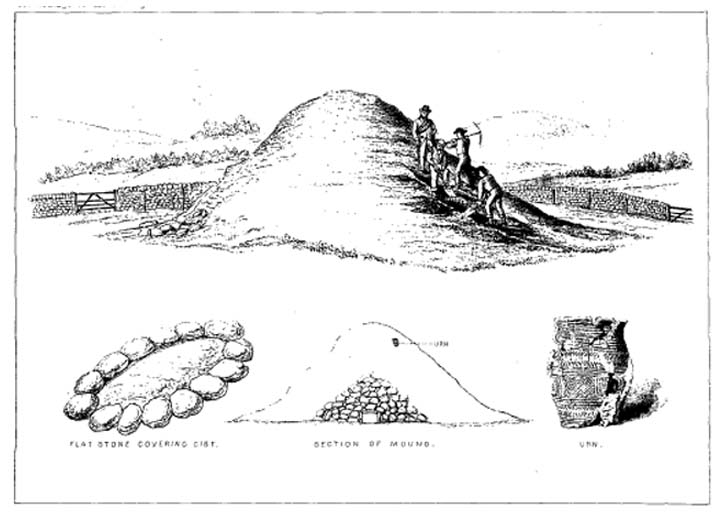

The Fairy Knowe was first excavated in 1868 by Sir J.E. Alexander and his team, when their measurements found it to be some 80 yards in circumference, 78 feet across and 21 feet high — compared to less than 60 feet across and only 8 feet tall today. The findings were recorded in one of the early PSAS reports, and more recently a synopsis of the account was made of it by the Royal Commission (1963) lads who summarized his early findings and told:

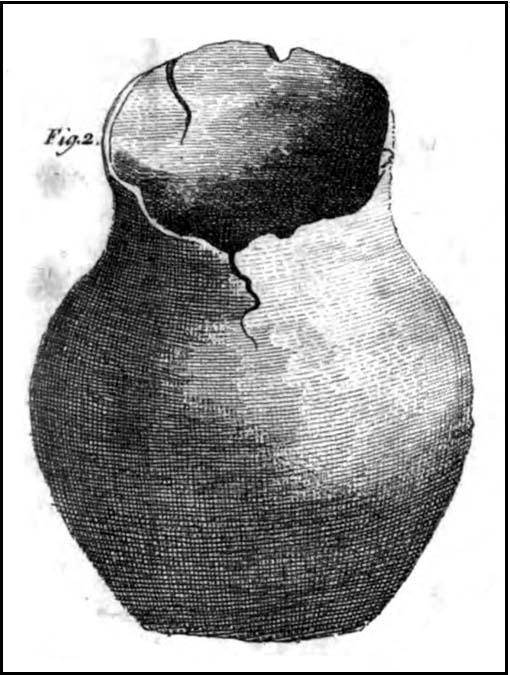

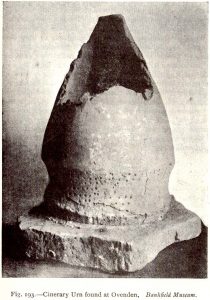

“The excavation revealed a cist in the centre of the cairn, laid on the original surface of the ground and measuring 2ft 6in in length, 1ft 6in in breadth and 3ft in depth. Its walls were formed partly of upright slabs and partly of small stones laid horizontally, while the floor and the roof each consisted of a single slab. Within it there was a deposit, 6in in depth, of black earth, charcoal and fragments of human bone among which pieces of a skull were conspicuous. The cist was covered by a heap of large stones, 8ft in diameter and 13ft in height, and this in turn was covered with earth, in which there were charcoal, blackened stones, fragments of human and animal bones and unctuous black earth. Among these remains were found six flint arrowheads, a fragment of what was once thought to be a stone spear-head, and a piece of pine which, it was suggested, might have formed part of a spear-shaft.”

Also, near the top of the cairn in the fairy mound, Sir Alexander’s team located a prehistoric beaker vessel and fragments of what they thought were other beakers pots. Archaeologist Richard Feachem (1977) also mentioned this site in his gazetteer, simply copying the words of previous researchers.

Other prehistoric cairns can be found nearby: one in Cuparlaw Woods less a mile north; plus the Pendreich cairns on the edge of the moors just over 1 mile to the northeast.

Folklore

Obviously an abode of the faerie folk in bygone times, the tales of the place are sadly fading from local memory… Mr Alexander (1868) thought this place may have been an important site for the Pictish folk, and he may well have been correct, as the legendary hill of Dumyat (correctly known as Dun Myat) 2 miles east of here has long been regarded as an outpost of one Pictish tribe.

The main piece of folklore attached to this place relates to its very name and how it came about. In R.M. Menzies (1912) rare work on the folklore of the Ochils, he narrates the local tale that used to be spoken, which describes a procession here from the Fairy Well, just over a mile to the east. Whether this folktale relates to some long lost actual procession between the two sites, we don’t know for sure. Mr Menzies told:

“Once upon a time, when people took life more leisurely, and when the wee folk frequented the glens and hills of Scotland, there was one little fairy whose duty it was to look after certain wells renowned for their curative properties. This fairy was called Blue Jacket, and his favourite haunt was the Fairy Well on the Sheriffmuir Road, where the water was so pure and cool that nobody could pass along without taking a drink of the magic spring. A draught of this water would have such a refreshing effect that the drinker could go on his journey without feeling either thirsty or hungry. Many travellers who had refreshed themselves at the Fairy Well would bless the good little man who kept guard over its purity, and proceed upon their way dreaming of pleasant things all the day long.

“One warm day in June, a Highland drover from the Braes of Rannoch came along with a drove of Highland cattle, which he was taking to Falkirk Tryst, and feeling tired and thirsty he stopped at the Fairy Well, took a good drink of its limpid water, and sat down beside it to rest, while his cattle browsed nearby. The heat was very overpowering, and he fell into a dreamy sleep.

“As he lay enjoying his noonday siesta, Blue Jacket stepped out from among the brackens and approaching the wearied drover, asked him whence he came. The drover said:

“‘I come from the Highland hills beside the Moor of Rannoch; but I have never seen such a wee man as you before. Wha’ may you be?’

“‘Oh,’ said the fairy, ‘I am Blue Jacket, one of the wee folk!’

“‘Ay, ay man, ye have got a blue jacket, right enough; but I’ve never met ony o’ your kind before. Do ye bide here?’

“‘Sometimes; but I am the guardian of the spring from which you have just been drinking.’

“‘Weel, a’ I can say is that it is grand water; there is no’ the likes o’t frae this to Rannoch.’

“‘What’s your name?’ asked the fairy.

“‘They ca’ me Sandy Sinclair, the Piper o’ Rannoch,’ was the reply.

“‘Have you got your pipes?’ asked Blue Jacket.

“‘Aye, my mannie, here they are. Wad ye like a tune? Ye see there’s no’ a piper like me in a’ Perthshire.’

“‘Play away then,’ said Blue Jacket.

“Sandy Sinclair took up his pipes and, blowing up the bag, played a merry Highland reel. When he finished, he was greatly surprised to see above the well a crowd of little folk, like Blue Jacket, dancing to the music he had been playing. As he stopped they clapped their little hands and exclaimed, ‘Well done Sandy! You’re the piper we need.’

“Thereupon Blue Jacket blew a silver whistle, which he took from his belt, and all the wee folk formed themselves into a double row. Blue Jacket then took the Highland piper by the hand, led him to the front of the procession, and told him to play a march. Sandy felt himself unable to resist the command of the fairy, and, putting the chanter into his mouth, blew his hardest and played his best, marching at the head of the long line of little people, who tripped along, keeping time to the strains of the bagpipes. Blue Jacket walked in front of the piper, leading the way in the direction of the Fairy Knowe.

“Sandy Sinclair never marched so proudly as he did that day, and the road, though fairly long, seemed to be no distance at all; the music of the pibroch fired his blood and made him feel as if he was leading his clansmen to battle. When the Fairy Knowe was reached, the wee folk formed themselves into a circle round the little hill, and sang a song the sweetest that ever fell upon the ears of the Highlandman. Blue Jacket once more took his whistle and, blowing three times upon it, held up his hand, and immediately the side of the knoll opened. Bidding the piper to play on, Blue Jacket led the procession into the interior; and when all were inside, the fairies formed themselves into sets, and the piper playing a strathspey, they began dancing with might and main.

“One dance succeeded another, and still Sandy played on, the wee folk tripping it as merrily as ever. All thoughts of Sandy’s drove had gone quite out of his head, and all he thought of now was how best to keep the fairies dancing: he had never seen such nimble dancers, and every motion was so graceful and becoming as made him play his very best to keep the fun going. Sandy Sinclair was in Fairyland, and every other consideration was forgotten.

“Meanwhile his cattle and sheep were following their own sweet will, the only guardian left to take care of them being his collie dog. This faithful animal kept watch as well as he could, and wondered what had become of his master. Towards evening another drover came along with his cattle for the same tryst. He knew the dog at once, and began to pet the animal, saying at the same time, ‘Where’s your master, Oscar? What’s become o’ Sandy?’

“All the dog would do was to wag his bushy tail, and look up with a pleading air, as if to say, ‘I don’t know; will you not find him?’

“‘My puir wee doggie, I wonder what’s come over Sandy? It’s no like him to leave his cattle stravaiging by the roadside. Ay ay man; and at the Fairy Well too! Indeed, this looks unco bad.’

“The newcomer, who was also a Highlander, made up his mind to spend the night with his own drove and that of Sandy Sinclair, thinking that the missing man would turn up in the morning. But when the morning came there was no sign of Sandy.

“Taking Sandy’s collie and leaving his own dog in charge of the combined droves, he said, ‘Find master, Oscar!’ The wise beast sniffed around for a little and then trotted off in the direction taken the day before by Sandy Sinclair and the fairies. By and by they reached the Fairy Knowe; but there was nobody there as far as the drover could see. The dog ran round and round the knoll, barking vigorously all the time, and looking up into the face of the drover as if to say, ‘This is where he is; this is where he is.’ The drover examined every bit of the Fairy Knowe, but there was no trace of Sandy Sinclair. As the drover sat upon the top of the Fairy Knowe, wondering what he should do next, he seemed to hear the sound of distant music. Telling the faithful dog to keep quiet, he listened attentively, and by-and-by made out the sound of the pibroch; but whether it was at a long distance or not, he could not be certain. In the meantime, the dog began to scrape at the side of the mound and whimper in a plaintive manner. Noticing this, the drover put his ear to the ground and listened. There could be no mistake this time: the music of the pibroch came from the centre of the Fairy Knowe.

“‘Bless my soul!’ exclaimed Sandy’s friend. ‘He’s been enticed by the fairies to pipe at their dances. We’ll ne’er see Sandy Sinclair again.’

“It was as true as he said. The Piper of Rannoch never returned to the friends he knew, and the lads and lasses had to get another piper to play their dance music when they wished to spend a happy evening by the shore of the loch. Long, long afterwards, the passers-by often heard the sound of pipe music, muffled and far away, coming from the Fairy Knowe; but the hidden piper was never seen. When long absent friends returned to Rannoch and enquired about Sandy Sinclair, they were told that he had gone to be piper to the wee folk and had never come home again.”

References:

- Alexander, J.E., “Opening of the Fairy Knowe of Pendreich, Bridge of Allan,” in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 7, 1868.

- Feachem, Richard, Guide to Prehistoric Scotland, Batsford: London 1977.

- Fergusson, R. Menzies, The Ochil Fairy Tales, David Nutt: London 1912.

- Roger, Charles, A Week at Bridge of Allan, Adam & Charles Black: Edinburgh 1853.

- Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments Scotland, Stirling – volume 1, HMSO: Edinburgh 1963.

- Stevenson, J.B., Exploring Scotland’s Heritage: The Clyde Estuary and Central Region, HMSO: Edinburgh 1985.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.