Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – NT 200 522

Also Known as:

-

La Mancha

Archaeology & History

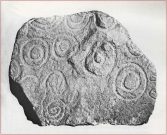

This is what I’ve come to term dyslexic cup-and-rings, due simply to the fact that it’s a cup-and-ring stone carving, but the cup in the centre hasn’t been carved out or pecked away. They’re rare – but for some odd reason, a small cluster of them occurs in this part of lowland Scotland. The Drumelzier carving 13 miles SSW is one; the Carnwath carving 14 miles west is another; 14 miles to the south, the multiple-ringed carving in the Woodend cairn had no defined pivotal cup; and in Childe & Taylor’s (1938) short piece on the Hawthornden petroglyphs near Roslyn (less than 10 miles northeast), they noted—like Simpson & Thawley (1972) years later—the peculiarity of “the complete absence of cups”, akin to Lamancha’s carved rings. (although we should be cautious about the archiac nature of the Hawthornden carvings)

The carving here was first mentioned by one of the great petroglyphic pioneers James Simpson (1866; 1867):

“A broken slab, about two feet square, covered with very rude double rings and a spiral circle, was found by Mr Mackintosh, at La Mancha, in Peeblesshire, in digging in a bank of gravel. There were some other large stones near it; none of them marked. Possibly this stone, therefore, is sepulchral in its character.”

Eoin MacWhite (1946) was somewhat sceptical of Simpson’s “sepulchral” association, simply due to there being no account of a burial here. But in Simpson & Thawley’s (1972) survey of passage grave art, they thought the Lamancha carving was from “a possible cist slab.” We might never know for sure one way or the other.

The carving ended up living in Edinburgh’s National Museum where it should, hopefully, still be on display. As a result of this, it received the attention of the Royal Commission doods who gave a good description of the design in their Peeblesshire Inventory (1967). They state that it

“is irregular in shape and has maximum dimensions of 2ft 6in by 1ft 10in; it averages 4in in thickness. The markings, which have all been formed by the pecking technique, occur mainly on one face, the most common symbol being single or double rings. There are four complete double-ring symbols, in which the outer rings measure from 5in to 7in in diameter, and the inner rings from 2in to 4in. Round the margin of the face there are the broken arcs of five more double-ring symbols and of five single rings and one small V -shaped figure. As well as the ring markings there is a double-spiral, each lobe of which measures about 4in in diameter. In one lobe the spiral has two and a half turns and in the other only one turn. In addition, in a space which is otherwise free of markings, there is an area, about 4in square, heavily pitted with punch-marks measuring one-eighth of an inch across and one-sixteenth of an inch in depth. A remarkable feature of the stone is that three incomplete single ring symbols have been made on one edge. They have been formed by the same technique and measure 3in across; as in all the other symbols, the grooves themselves measure about half an inch in width and about one-eighth of an inch in depth.”

References:

- Childe, V.G. & Taylor, John, “Rock Scribings at Hawthornden, Midlothian,” in Proceedings Society Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 73, 1938.

- McWhite, Eoin, 1946 “A New View on Irish Bronze Age Rock-Scriblings”, in Journal Royal Society Antiquaries, Ireland, vol. 76, 1946.

- Morris, Ronald W.B., “The Cup-and-Ring Marks and Similar Sculptures of South-West Scotland,” in Transactions of the Ancient Monuments Society, volume 14, 1967.

- Morris, Ronald W.B., “The Cup-and-Ring and Similar Early Sculptures of Scotland; Part 2 – The Rest of Scotland except Kintyre,” in Transactions of the Ancient Monuments Society, volume 16, 1969.

- Morris, Ronald W.B., The Prehistoric Rock Art of Southern Scotland, BAR: Oxford 1981.

- Ritchie, Graham & Anna, Edinburgh and South-East Scotland, Heinnemann: London 1972.

- Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments, Scotland, Peeblesshire – volume 1, Aberdeen University Press 1967.

- Simpson, D.D.A. & Thawley, J.E., “Single Grave Art in Britain,” in Scottish Archaeological Forum, no.4, 1972.

- Simpson, J.Y., “On Ancient Sculpturings of Cups and Concentric Rings,” in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 6, 1866.

- Simpson, James, Archaic Sculpturings of Cups, Circles, etc., Upon Stones and Rocks in Scotland, England and other Countries, Edmonston & Douglas: Edinburgh 1867.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.