Standing Stones: OS Grid Reference – NS 7945 9246

Also Known as:

- Canmore ID 46226

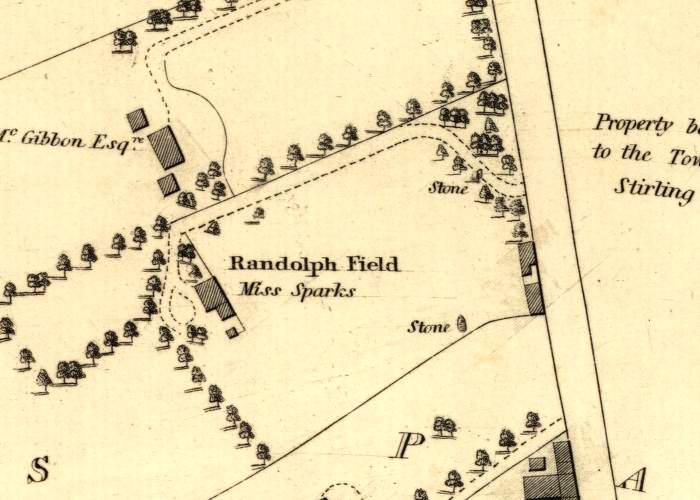

- Randolph Field Stones

Pretty easy to find. Head down the B8051 road south, out of Stirling, for a ¼-mile. Keep your eyes peeled for the central police station on your right as you come out of town. The stones are on the grassy forecourt in front of the police station!

Archaeology & History

It’s amazing that these stones are still standing! Jut out of the city centre, very close to the main road and right outside the central police station: if these standing stones would have stood anywhere in England, they’d have been destroyed. Thankfully, the Scots have more about them regarding their history, traditions and antiquities.

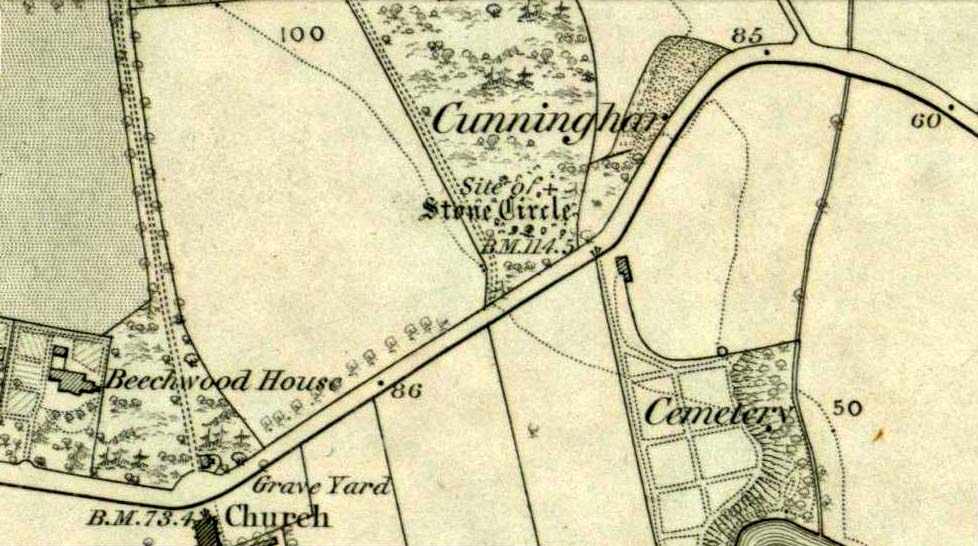

Of the two stones that remain here, they stand in (just about) the same position that they were shown as on an 1820 map of Stirling. The northernmost of the two is about 3½-feet tall and rests upright against the edge of the track and lawn; whilst its taller companion — knocking close on to six-feet tall — stands proudly near the middle of a well-kept lawn less than 50 yards away. Once you’ve found one, the other’s easy to spot!

It’s obvious that the larger of the two stones was cut down at some time in the recent past, as there are several blatant cuts where the standing stone had been snapped into at least three portions — but whoever did the damage was given a bittova bollocking, as the stone was cemented back into its near-original form and stood back upright again. To this day, as one of the female officers coming out of the station indignantly told me, “they’re protected!” Long may they stay that way!

In Mr A.F. Hutchinson’s (1893) early description of these stones he told that they stood “in a line from SW to NE — the line of direction making an angle of 235° with the magnetic north.

“The southwest stone stands 4ft above the ground. The portion underground measures 2ft 5in; so that in all it measures 6ft 5in. Its girth is 6ft 6in. It is four-sided in shape—nearly square—three of the faces measuring each 21 inches, and the fourth 15 inches. The northeast stone is smaller and less regular in form. Its height above ground is 3ft 6in, and its girth 4ft 6in. Both stones are pillars of dolerite, of the same material as the pillar stones of the Castle rock, from which place they have apparently been brought. The larger stones shows some marks on it, which have been supposed to be artificial. They are , however, merely the natural joints characteristic of these blocks…”

Folklore

Like many standing stones scattering our isles, this site possesses the old tradition of them marking a battle — in this case, the Battle of Bannockburn. Once again, Mr Hutchinson (1893) wrote:

“The local tradition as to the origin and meaning of these stones is well-known. It is thus stated by (William) Nimmo in his History of Stirlingshire, p.84…: ‘Two stones stand to this day in the field near Stirling, where Randolph, Earl of Murray, and Lord Clifford, the english general, had a sharp encounter, the evening before the great battle of Bannockburn.’ Again, p.193:- ‘To perpetuate the memory of this victory…two stones were reared up in that field and are still to be seen there.’ …The Old Statistical Account of St. Ninians (Rev. Mr Sheriff, 1796), makes the same statement, p.406-8:- ‘In a garden at Newhouse, two large stones still standing were erected in memory of the battle fought on the evening before the battle of Bannockburn, between Randolph and Clifford.'”

Yet the name ‘Randolphfield’ is apparently no older (in literary records) than the end of the 17th century and the thoughts of Hutchinson and other local historians is that the two stones here, whilst perhaps having some relevance to an encounter between the Scots and the invading english, were probably erected in more ancient times.

References:

- Hutchinson, A.F., “The Standing Stones of Stirling District,” in The Stirling Antiquary, volume 1, 1893.

- Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments Scotland, Stirling – volume 1, HMSO: Edinburgh 1963.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian