Healing Wells: OS Grid Reference – NS 79504 97686

Also Known as:

- Airthrey Spa

- Airthrey Springs

- Bridge of Allan Spa

- Canmore ID 317260

Getting Here

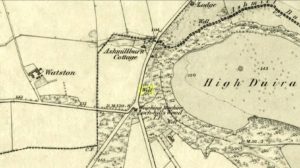

Site shown on 1865 OS map

The old well-house is accessed easily. From the main road of Henderson Street (or A9), that runs through the town, as you approach the main shopping area, go up Alexander Drive, then immediately turn right up Well Road. 100 yards up, take your first right again along Kenilworth Road and then first right up Mine Road. 100 yards or so along here, as you reach the tennis courts on your right, a small crumbly-tumbly building is to your left, just by the car-park to the hotel, with some old trees hiding its presence. You can’t get into it and the waters therein sound to have fallen silent.

Archaeology & History

In 1761, the great writer Daniel Defoe in his Tour across Britain, found himself visiting a healing spring under the western reaches of the Ochils:

“Airthrey Well, two miles north of Stirling, flows from a mountain, where is a copper mine, with some mixture of gold; the water is very cold, and being tinctured with the minerals it flows through, is of use against outward distempers.”

Airthrey Wellhouse in ruins

Perhaps the earliest literary description of this site, the Bridge of Allan that we see today was little more than a stretch of old abodes, reaching into woodland above the crystal clear river and burns, chiming with countless fauna and that rich chorus of colours that pre-date the Industrialist’s ‘progress’. The old hamlet was said by Robert Chambers (1827) to be “a confusion of straw-roofed cottages and rich massy trees; possessed of a bridge and a mill, together with kail-yards, bee-skeps, colleys, callants, and old inns.” But all of this was about to change.

In the old woods on the northwest slopes above the hamlet was indeed an old copper mine as Defoe described, and housed therein were a number of mineral springs–six of them according to the early reports of Forrest (1831) and Thomson. (1827) They were obviously “known to the country people,” said Thomson, and had been “used by them as an occasional remedy for more than forty years”; although in Forrest’s very detailed account of these wells, he told how

“one of the old miners, an intelligent man and an enthusiastic admirer of the medicinal virtues of these waters, informs me, that they have been known for at least one hundred years.”

This comment was echoed a few years later when Charles Roger (1853) wrote his extensive book on the village.

It was in the 1790s when the mineral waters were channeled out of the mines for the first time, and Mr Forrest told that they were collected lower down the slope,

“in a wooden trough, for the use of the miners, and of the country people, some of whom used it as an aperient, whilst others, deeming the water impregnated with common salt merely, employed it for culinary purposes. …It was…much used as a medicine by the country people of the neighbourhood who attended regularly every Sunday morning to partake of it.”

Airthrey waters channeled along the long trough (Robert Mitchell 1831)

The fact that Sunday mornings was when people came here tell us that the Church had something to do with the timing; strongly implying that the wells possessed earlier indigenous traditions—probably similar to those practiced at the Christ’s Well, the Chapel Well and countless others across the country. But written records on this are silent.

The main history of the Airthrey Springs is of them becoming famous Spa Wells and, much like Harrogate in Yorkshire, were responsible for the very growth of Bridge of Allan itself. Oddly enough, this came about a few years after the copper mines were closed in 1807. This wouldn’t have stopped some of the local people still getting into them and drinking the waters when needed—but the written records simply tell that, for a few years at least, their reputation faded. Around the same time in the village of Dunblane, just a few miles to the north, another Spa Well had been discovered and it was attracting quite a lot of those rich wealthy types—bringing fame and money to the area. As a result of this, the medicinal virtues of the Airthrey Springs were revived thanks to the attention of the local lord, a Mr Robert Abercromby, who thought that Bridge of Allan could gain a reputation of his own. And so in the winter of 1821-22, Abercromby procured the research chemist Thomas Thompson to analyse the medicinal waters at Airthrey and have them compared with the ones at Dunblane. He was in luck! Not only were they medicinal, they were incredibly medicinal!

Dr Thomson then wrote a series of articles in various academic journals in the early 19th century—each espousing, not just the health-giving property of the Airthrey waters, but lengthy chemical analyses outlining the active constituents. To his considerable surprise he found that the Airthrey waters were as good as any of the great spa towns in England at Harrogate, Buxton, Bath and Leamington. Their virtues were so good that Mr Forrest (1831) doubted any of the Spa Wells in England were as beneficial as the waters here! R.M. Fergusson (1905) echoed this sentiment in his massive work on the adjacent parish of Logie, calling the Airthrey springs “the Queen of Scottish Spas”!—and these accolades prevailed long after Dr Thomson’s analyses. He wrote:

“At Airthrey there are six springs containing, all of them, the same saline constituents, but differing a good deal in their relative strengths. I analyzed two of these during the winter of 1821-22, and the other four during the autumn of 1827.”

He found that, in varying degrees, the main constituents were salt, muriate of lime, sulphate of lime and muriate of magnesia. At that time, in medical circles, these ingredients were beauties! As Mr Logie (1905) said:

“This mineral water has been for long distinguished as a specific for derangements of the stomach and liver, and skin and chest diseases, rheumatism, gout, sciatica, and nerve affections…”

Thomson’s initial findings were much to the liking of Mr Abercromby; for hereafter, he realised, all and sundry who could read and travel to the country spas in England and beyond, would visit Bridge of Allan and bring with it great trade. So Abercromby quickly,

“caused the water of the two Springs analysed by Dr. Thomson, one of which was characterised by its strength, the other by its comparative weakness, to be carefully collected and conveyed apart in earthen pipes, to two stone troughs placed in a convenient situation, from which it was raised by two well-constructed forcing pumps. Over these pumps a commodious house was erected.

In 1822, several thousand copies of Dr. Thomson’s analyses were circulated; and the water acquired immediate celebrity. Invalids from all parts of the country, but especially from Glasgow and its vicinity, resorted to Airthrey. Every house, in fact, in its neighbourhood, however mean and incommodious, was occupied by strangers; and so great was the popularity of the new springs that even in 1823 they threatened to supersede all the other same springs of Scotland.”

The success of these medicinal waters created the town itself and, unlike many other spa wells, this one continued to be used until the end of the 1950s. Its demise came when, in one financial year, only two people came to “take the cure,” as it was called.

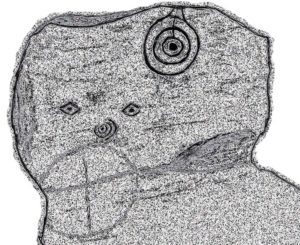

Side wall of ruined wellhouse

If you visit the well-house nowadays, it’s in rather poor condition and will be of little interest unless you’re a devout architectural fanatic. It’s thought to be the earliest surviving building associated with this spa town, said by Mr Roger (1853) to have been built in 1821. Shown on the first OS-map of the area, adjacent buildings were constructed to accommodate the overflow of people who came here. And in the woodlands above, if you look around halfway up the slopes, an old trough has water running into it just by the side of a path. This, say some local folk, is the trickling remains of the medicinal waters, still used occasionally by some people…

References:

- Durie, Alastair J., “Bridge of Allan: Queen of the Scottish Spas,” in Forth Naturalist & Historian, volume 16, 1993.

- Erskine, John, Guide to Bridge of Allan, Observer Press: Stirling: 1901.

- Fergusson, R. Menzies, Logie: A Parish History – 2 volumes, Alexander Gardner: Paisley 1905.

- Forrest, W.H., Report, Chemical and Medical, of the Airthrey Mineral Springs, John Hewit: Stirling 1831.

- Morris, Ruth & Frank, Scottish Healing Wells, Alethea: Sandy 1982.

- Roger, Charles, A Week at Bridge of Allan, Adam & Charles Black: Edinburgh 1853.

- Stewart, Peter G., Essay on the Dunblane Mineral Springs, Hewit: Dunblane 1839.

- Thomson, Thomas, “On the Mineral Waters of Scotland,” in Glasgow Medical Journal, volume 1, 1827.

- Turner, E.S., Taking the Cure, Michael Joseph: London 1967.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian