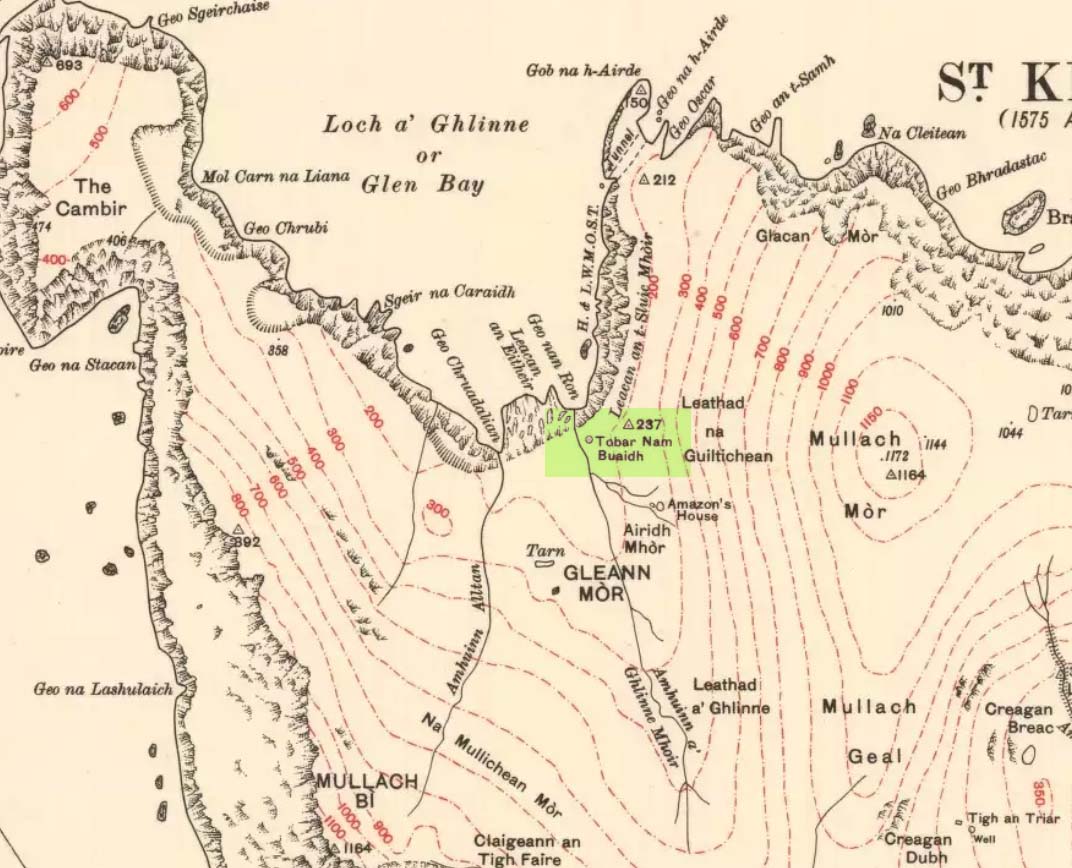

Legendary Stone: OS Grid Reference – NF 101 996?

Also Known as:

- Stone of Knowledge

Archaeology & History

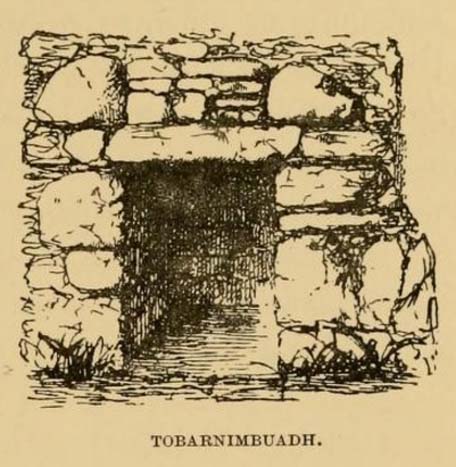

This stone has very similar qualities to the one found upon Mullach-geal, ⅔ of a mile to the west, as a place where ritual magick was performed. And, just like the Mullach-geal stone, we only have an approximate position of its whereabouts: “behind the village”, as Mr Sands (1878) said. The same words were used by other St Kildan writers when it came to describing the whereabouts of Tobar Childe, so we must assume it to be reasonably close to the old well.

Folklore

Mr Sands seems to be the first person to write about it, telling us,

“At the back of the village is a stone, which does not differ in external appearance from the numerous stones scattered around, but which was supposed to possess magical properties. It is called Clach an Eolas, or Stone of Knowledge. If any one stood on it on the first day of the quarter, he became endowed with the second sight — could “look into the seeds of Time,” and foretell all that was to happen during the rest of the quarter. Such an institution must have been of great value in Hirta, where news are so scanty. To test its powers I stood on it on the first day of Spring (old style) in the present year, but must acknowledge that I saw nothing, except two or three women laden with peats, who were smiling at my credulity.”

Charles MacLean (1977) mentioned the stone a hundred years later, but seems to have just copied this earlier description. Does anyone up there know its whereabouts?

References:

- MacLean, Charles, Island on the Edge of the World, Canongate: Edinburgh 1977.

- Sands, J., Out of the World; or Life in St. Kilda, Maclachlan & Stewart: Edinburgh 1878.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.