Standing Stone: OS Grid Reference – SE 01974 27684

Also Known as:

- Saville’s Low

From the village of Midgley, high above the A646 Halifax-to-Todmorden road, travel west along the moorland road until you reach the sharp-ish bend in the road, with steep wooded waterfall to your left and the track up to the disused quarry of Foster Clough. Go up the Foster Clough track for 100 yards and, when you reach the gate in front of you, go over it but follow the line of the straight walling uphill by the stream-side (instead of following the path up the quarries) all the way to the top. Here you’ll see the boundary stone of Churn Milk Joan.

Archaeology & History

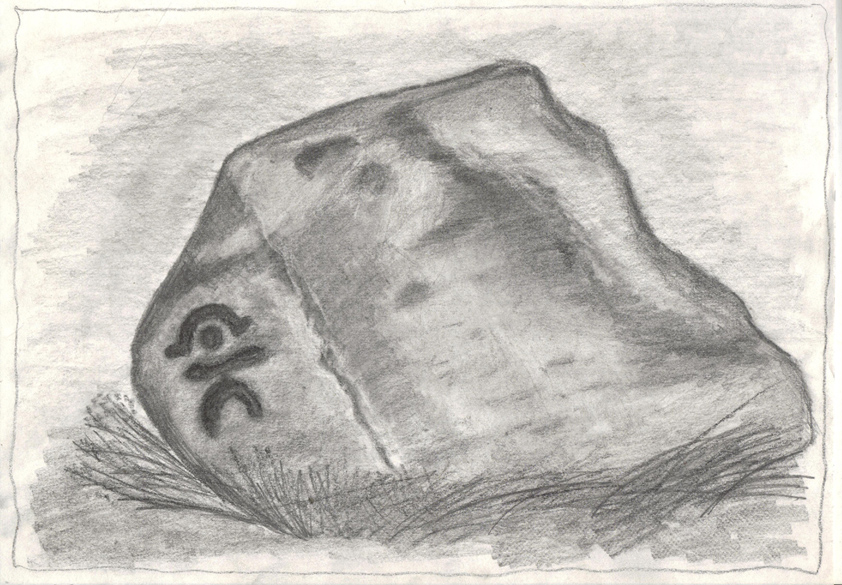

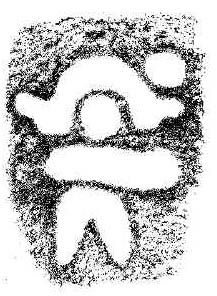

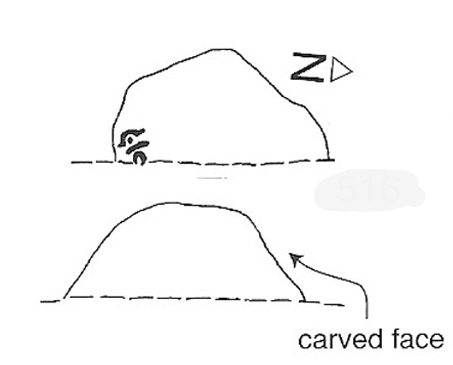

The present large standing stone you see before you isn’t prehistoric. However, the small broken piece on the ground by its side may have been its prehistoric predecessor; and there is certainly something of an archaic nature here — albeit a contentious one — as we find old cup-markings cut into its eastern face.

The upright is roughly squared and faces the cardinal points. It was described in Mr Heginbottom’s (1977) unpublished survey on Calderdale rock art, where he described there being a few cup-markings inscribed on its east- and south-facing edges, some of which may be prehistoric — though they would obviously have had to have been carved upon the upright stone when it still lay earth-fast. However, we must posit the the notion (unless some of you have better ideas) that the tradition of etching cup-marks onto rocks was still occurring in this part of Yorkshire until the late Middle Ages, as this stone was, as we know from boundary records, only placed upright to mark the meeting of the three boundaries of Wadsworth, Hebden Royd and Sowerby.

Churn Milk Joan’s other name, Saville’s Low, originates from the great Saville family who owned great tracts of land across the region in the fourteenth century, possibly when the Churn Milk Joan we see today was created. The word “lowe” may derive from the old word meaning, “moot or gathering place,” which this great stone probably served as due to its siting at the junction of the three townships.*

Folklore

In modern times the stone has become a focus for a number of local pagans and New Agers who visit and ‘use’ the site in their respective ways at certain times of the day, albeit estranged (ego-bound) from the original mythic nature of the site.

The name of the stone comes from an old legend about a milk-maid named Joan who, whilst carrying milk across the moors between Luddenden and Pecket Well, got caught in a blizzard and froze to death. When her body was found many days later, the stone we see here today was erected to commemorate the spot where she died. Although such a scenario is quite likely on these hills, as Andy Roberts (1992) said,

“Considering the sheer amount of sites with similar legends this explanation is unlikely to be true and we should looker deeper for the meaning behind Churn Milk Joan, to be found in its positioning in the landscape and ourindividual feelings about it.” [see profiles for the Two Lads and the Lad o’ Crow Hill sites)

The monolith’s other title, Churnmilk Peg, is the name given to an old hag who is said to be the guardian of nut thickets. How this female sprite came to find her abode upon these high hills is somewhat of an enigma, but it was first stated as such in an article by Andy Roberts (1989) in “Northern Earth Mysteries” magazine. E.M. Wright (1913) noted this supernatural creature in her work on folk dialect, describing it as a West Yorkshire elemental who, along with another one known as Melsh Dick:

“are wood-demons supposed to protect soft, unripe nuts from being gathered by naughty children, the former being wont to beguile her leisure by smoking a pipe.”

Another legend of the stone tells how it is said to spin round three times on New Year’s Eve when it hears the sound of the midnight bells at St. Michael’s church (St. Michael was a dragon-slayer) at Mytholmroyd in the valley below. Another piece of folklore tells that coins used to be left in a small hollow at the very top of the stone which, according to Haslem (1981), was “a gift to the spirit world, to bring luck” – a common folk motif. It may equally originate from the custom of it as a plague stone. This tradition of leaving coins atop of the stone is still perpetuated by some local folk.

Mr Haslem also made some interesting remarks about the nature of Churn Milk Joan standing as a boundary stone, representing something which stands not just as a physical boundary, but as a boundary point between this and the Other- or spirit world. In folklore, streams and rivers commonly carry this theme. But here on Midgley Moor, as a standing stone at the junction of three boundaries, we may be looking at the place as an omphalos: a centre point from which the manifold worlds unfold. (see Almscliffe Crags, the Ashlar Chair and the Hitching Stone)

The other motif here, of milk and snow [both white], have been speculated to represent power of the sun at midwinter, and geomantically we find the position of the stone in the landscape exemplifying this: it stands midway in the moorland scenery facing south, the direction of solar power, yet is bounded as an equinox marker from east and west. The winter tales it has nestled around it are merely complementary occult augurs of its more wholesome elements at this point in the hills.

There is however, another much more potent element that has not been conveyed about the site and its folklore—and one which has more authenticity and primary animistic quality. Regardless of ‘Joan’ or ‘Peg’ being the elemental preserved in the landscape title, the ‘churning’ in its name and the ‘spinning’ of the stone in myth at the end of one year and the start of the next at New Year, are folk memories of traditional creation myths that speak of the cyclical seasons endlessly perpetuated year after year after year, in what Mircea Eliade (1954) called the ‘myth of the eternal return.’ As season follows season in the folk myths of our ancestors, everything related to the natural world: a world inhabited (as it still is) by feelings and intuitions learned from an endless daily encounter, outdoors, with the streams, hills, gales, snow and fires. Their entire cosmology, as with aboriginal people the world over, saw the cycles of the year as integral parts of their daily lives. Here, at Churn Milk Joan with its central landscape position along an ancient boundary, the churning and turning of the year was commemorated and mythologized year after year after year; with maybe even the Milky Way being part of the ‘milk’ in its title, from which, in the shamanistic worlds that were integral to earlier society, the gods themselves emerged and came down to Earth.

References:

- Bennett, Paul, The Old Stones of Elmet, Capall Bann: Milverton 2001.

- Eliade, Mircea, The Myth of the Eternal Return, Bollingen 1954.

- Haslem, Michael, “Churn Milk Joan: A Boundary Stone on Midgley Moor,” in Wood and Water, 1:8, 1980.

- Heginbottom, J.A., “The Prehistoric Rock Art of Upper Calderdale and the Surrounding Area,” Yorkshire Archaeology Society 1977.

- Ogden, J.H., “A Moorland Township: Wadsworth in Ancient Times,” Proceedings of the Halifax Antiquarian Society, 1904.

- Robert, Andy, “Our Last Meeting,” in NEM 37, 1989.

- Robert, Andy, Ghosts and Legends of Yorkshire, Jarrold: Sheffield 1992.

- Wright, Elizabeth Mary, Rustic Speech and Folk-Lore, Oxford University Press 1913.

* The great stone at the cente of the Great Skirtful of Stones, Burley Moor, which previously stood at the centre of the Grubstones Circle, was just such a moot stone. Upon it is carved the words “This is Rumble’s Lawe”.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.