Holy Well: OS Grid Reference – NS 79690 93012

Also Known as:

- Canmore ID 46210

- St. Ringan’s Well

Getting Here

St Ninian’s Well, Stirling

A short distance south out of Stirling town centre, along Port Street where it meets with Ninian’s Road, walk across at the traffic lights then turn immediately left down Wellgreen Road. Barely 100 yards down (before you reach the roundabout), note the path on your right. Walk along here and as it bends round into the car-park, look to your left and see the small ivy-covered building hiding away in below you, with an information plaque at its side.

Archaeology & History

“St Ninian’s” is a district unto itself on the south side of the ancient city of Stirling—and it has this holy well (and the demolished chapel that once stood by its side) to thank for this. James Johnston’s (1904) place-name study of the region showed that it had acquired its association with St Ninian as early as 1242 CE when it was described, “Ecclesia Sancti Niniani de Kirketoune.” It was mentioned again in 1301 CE as the site of “Saint Rineyan”, or St Ringan, which was the other name given to this saint who spent much of his time at Whithorn, Galloway, where he “preached the gospel among the southern Picts.” (Attwater 1965)

The waters in the building

The old well building

At some later date, Ninian is thought to have ventured north and sanctified this already renowned water source which, in his day, would have been open and surrounded by ancient trees and an abundance of wild flowers and healing plants. But today, typically, it is hiding almost secretly away, behind locked doors and not in view for the general public. This needs to be changed! Standing outside of the unkempt and overgrown building, you can faintly hear these ancient waters still flowing within their darkened enclave.

It has been described in a number of local history books down the years, but a lot of the old stories and traditions have sadly moved into forgotten memories… The first major description of the site was by J.R. Walker (1883) who wrote freshly about it soon after his visit—despite being “disappointed” with the architectural features of the building built over the well; which is hardly the right attitude as far as I’m concerned! The waters, their natural environment, feeling and genius loci are the primary features to sacred wells—nottheir dissolution, nor the artifice of humans to contain and reduce the natural world at such a place! But, this aside: for the architects amongst you, here’s what Walker had to say about the well-house:

“Mr T.S. Muir, in his Characteristics of Old Church Architecture, mentions it as “a large vaulted building with a chamber above it, which is supposed to have been a chapel.” From this notice I was led to think something of interest would be found in the chamber; but as will be seen by the drawing…it is utterly destitute of any feature worthy of particular notice. On looking at the surroundings, however, which are all modern, and mostly new houses and streets in course of erection, I came to the conclusion that at no distant date the well was doomed, and that consequently I had better make a correct drawing of it.

“The lower chamber measures 16 feet by 11 feet 1 inch, and is covered with a vault running from end to end, measuring from floor to springing 2 feet 9 inches, and from floor to crown of arch 6 feet. At the end where the spring rises there is a square recess 1 foot 9 inches high and 1 foot 7 inches wide and 17 inches deep; and at the other end two recesses, the largest measuring 2 feet 7 inches in height, 1 foot 4 inches wide and 1 foot 4 inches deep, the other 8 inches high, 8 inches wide, and 8 inches deep. To what purpose these have been put I have formed no idea; they are on an average 12 inches from the floor to the sill. The side walls are 2 feet 9 inches thick, and the end gable 3 feet; the other gable, between the well chamber and the adjacent building, being about 2 feet 3 inches. The room above is the same size as the vaulted chamber below, and is divided by timber partitions to form a dwelling-house. There is an ordinary fireplace and press in the gable; the press, however, does not go down to the floor, but is simply a recess or “aumbry,” such as we see in old Scotch houses.

“The roof seems to have been renewed at no distant date, although some of the timbers are, without doubt, home-grown. The ground rises rapidly to the back, so that the entrance door to the house is level with the top of the vault; this door is simply splayed in the Scotch manner, with a square lintel over, and a relieving arch inside. The door to the well chamber is also splayed, and in like manner the windows; the largest window has been altered, and a new projecting sill put in.

“At present the well is used for washing purposes, and must have been so for a considerable length of time, if we may judge from the table of rates affixed to the building; and a channel has been formed down one side and along the bottom end to carry away the water, the floor being paved with stones. The vault inside is roughly dressed, very little labour seemingly having been bestowed upon it.

“In the New Statistical Account it is suggested that the chamber was used as a bath, and it also states that, “it is celebrated for its copiousness and its purity. It is a hardish water, but of low specific gravity, and much used for washing. It has been calculated that were all the waters proceeding from this spring forced into the pipes that supply the town, it would afford every individual not less than 14.03 gallons per twenty-four hours. Its temperature is very cold and it exhibits muriate of lime and sulphate of lime. It is also much used for brewing.”

“Externally the building is roughly cast, or in Scottish phraseology, harled.”

A few years later when J.S. Fleming (1898) wrote an account of the place in his survey of local holy wells, he described a number of other historical elements not included in Walker’s (1883) account, telling:

“RINGAN” is stated to be the Scoto-Irish form of Saint Ninian’s name. He is alleged to have come from Ireland in the fifth century. St. Ringan’s Chapel was one of three attached to St. Ninians, the others being at Skeoch—dedicated to the Virgin Mary—and at Cambusbarron. The remains of St. Ringan’s Chapel, a simple, barrel-vaulted chamber, 11 feet by 14 feet, built over the spring, are situated a few yards off Pitt Terrace, the upper walls having been built, in 1731, by order of the Stirling Town Council, and formed into a house for the convenience of the town’s washerwomen. A niche in the north-east wall has evidently been made to hold the image of the Saint; while there has also been a piscina in the same wall. The flow of water is enormous, and enters the building from under the south-west gable, and after passing through the little chamber, flows out at the east wall. In 1740, the Town Council, considering the large volume of water of some value, entertained the idea of having it conveyed into the town by means of pipes, and consulted an Edinburgh engineer with regard to the feasibility of the project. Nothing resulted from their efforts, however. The water of this spring is stated to be so cold in summer that people cannot stand in it for any length of time; while in winter, again, it is so warm that it rapidly thaws whatever is thrown into it. Smoke rises from it at times, hanging over it like a vapour on a frosty morning. These characteristics indicate that the waters must issue from a great depth in the ground.

“This Chapel was apparently held in high repute by King James IV., as in the Exchequer Rolls we find the following entries: — “1497, April 24. — Item to the King’s offerand in Saint Ringans Chapel, besid Strivelin, 14/.” ” Samen day to Schir Andro to get say a hental of messes of Saint Ringans, 20⋅/.”

The site was mentioned in the standard surveys of MacKinlay (1893) and Morris (1981), but with very little additional information.

Folklore

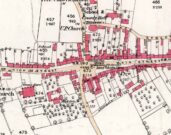

Ninian’s Well on 1832 map

St. Ninian’s festival date is September 16, but I’ve been unable to find any information about any practices here for that date. However, in 1659, St Ninian’s Well was mentioned as a site used in what the deluded criminal courts of the period called “a case of witchcraft”, against one Bessie Stevenson. The lady concerned told of performing quite normal herbal practices and similar animistic healing traditions, typical of those found universally in peasant cultures, but which the crazed church-goers saw as something completely different. Bessie told that for people who were either sick or bewitched, she would wash their clothes in the running waters of St. Ninian’s Well, to wash away any disease and cure the said person. It is likely that the waters here were commonly used for such rites, much as the christian priesthood still do at many ‘holy waters’ to this very day. Indeed, of the sacred waters here, St. Ninian himself was said to “have endowed it with peculiar virtues.” (Roger 1853)

References:

- Attwater, Donald, The Penguin Dictionary of Saints, Penguin: Harmondsworth 1965.

- Fleming, J.S., Old Nooks of Stirling, Delineated and Described, Munro & Jamieson: Stirling 1898.

- Johnston, James B., The Place-Names of Stirlingshire, R.S. Shearer 1904.

- MacKinlay, James M., Folklore of Scottish Lochs and Springs, William Hodge: Glasgow 1893.

- Morris, Ruth & Frank, Scottish Healing Wells, Alethea: Sandy 1982.

- Mould, D.D.C.P., Scotland of the Saints, Batsford: London 1952.

- Reid, John, The Place-Names of Falkirk and East Stirlingshire, Falkirk Local History Society 2009.

- Roger, Charles, A Week at Bridge of Allan, Adam & Charles Black: Edinburgh 1853.

- Ronald, James, Landmarks of Old Stirling, Eneas Mackay: Stirling 1899.

- Simpson, W.D., St. Ninian and the Origins of the Christian Church in Scotland, Oliver & Boyd: Edinburgh 1940.

- Walker, J. Russel, “‘Holy Wells’ in Scotland,” in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, vol.17 (New Series, volume 5), 1883.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian