Cup-Marked Stone: OS Grid Reference – NH 746 845

Also Known as:

- Canmore ID 14736

- Tain Museum Stone

Getting Here

No longer in its original position; the stone can now be found if you visit the Tain & District Museum, just off Tower Street, in towards St Duthus’ Church. The stone is upright around the side of the buildings adjacent, probably more accessible if you walk down Castle Brae, keeping your eyes peeled to your left. Otherwise, just ask the helpful people at the Museum.

Archaeology & History

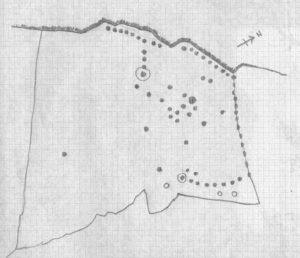

An intriguing stone with what may be a long and fascinating history behind it…. It was only rediscovered in the 1960s, when the farmer at Ardjachie (2½ miles northwest of Tain town centre) came across it in one of his fields. It’s not large or notable in any way, other than it possessing a couple of really peculiar symbols etched amongst a mass of otherwise standard neolithic and Bronze Age cup-marks. These other symbols are (as seen in Mark Taylor’s drawing, right) a very distinct ‘spoked wheel’ and what looks like a right-angled ‘tool’ or set-square of some sort. These symbols have brought with them notions from academics who are claim it has Pictish provenance. However, we must be very cautious of this idea….

The first written account of the stone was by Ellis Macnamara (1971) who gave a detailed description of the carving:

“Boulder found on Ardjachie Farm, now in Tain Museum. The boulder, of probably local old red sandstone, is uncut and very irregular in shape but has two principal faces; the maximum length is 1.7m; maximum width is 0.65m and on the maximum thickness is some 0.35m. The carvings are all on one face, which is much weathered; the opposing face is conspicuously less smooth so that it is possible that this stone was never set upright. The weathered face is covered with at least 30 ill-defined cup markings scattered over nearly the whole surface, though grouped towards one end; the average diameter of these cup markings is about 3 to 4cm, depth about 1.5cm. There are several indistinct lines among the cup markings and there is among the thickest cluster of cup markings a symbol like a ‘wheel’, with the outer ‘rim’ drawn as a fairly perfect circle, with a diameter at the outer edge of some 17cm. The ‘wheel’ has twelve ‘spokes’ and a single inner circle, or ‘hub’, with a diameter at the outer edges of about 4 or 5cm.”

Subsequent to Macnamara’s description, it’s been suggested that there are cup markings on both sides of the stone; but the ones on the other side are a little less certain. The stone itself almost typifies the cup-marked cist covers we find scattered all over the country—yet no burial or other structure was noted upon its discovery in the fields. It’s an oddity on various levels…

The spoked-wheel symbol and, moreso, the right-angled element, have led some to speculate that the symbol was carved in Pictish times; but there are problems with this on two levels at least. The cup-marks we know are neolithic or Bronze Age in origin, and their design always inclines to abstract non-linear forms, screwing egocentric analysis. But the ‘spoked wheel’ is more linear in nature. But as acclaimed petroglyph researchers from George Coffey (1912) to Martin Brennan (1983) show, this spoked wheel occurs in neolithic Ireland; and the identical symbol occurs in prehistoric carvings at Petit Mont in France (Twohig 1981), at Cairnbaan in Argyll (Royal Commission 2008) and there’s even a partial spoked-ring on the Badger Stone on Ilkley Moor! We have no need to jump into Pictish times to account for its origin and unless we have direct archaeological evidence to prove this, the academic Pictish association must be treated with a pinch of salt. It is nevertheless scarce amongst neolithic and Bronze Age carvings in Britain. Maarten van Hoek (1990) suggested it to be a variant on the ‘rosette’ design, also neolithic in origin. On the whole the symbol is interpreted as being the sun—which it may well be.

If you look carefully at the images above you can see, to the right of the ‘wheel’, a cup-marking surrounded by a ring of six-cups. It is possible that this may be an older variant of the spiked-wheel solar symbol. All speculation of course. The other peculiar element here is the curious right-angled design, below the ‘sun’. This symbol in particular is quite different from the early cup-marks and may have been carved at a much later date. In which case, this raises the potential for a continuity of tradition here… which mightjust bring in the Picts!

But the general problem with a Pictish assignment is that of the Picts themselves. If we ascribe the current anglocentric belief that the Picts only existed between the 3rd and 9th centuries (because we only have written records of them during that period), we are assuming the rather naive philosophy that anything before written history did not exist: a sort of blind-man’s Schrodinger’s Cat ideology, only really accepted by pseudo-historians. But if the Picts didhave something to do with this carving, we may indeed be talking about a continuity of tradition from the ancient past into the written period. Such an idea would be no problem in developed tribal cultures with an animistic cosmology—and that’s assuming that this stone was deemed as ‘special’ in some form or another to the local people. But all these are uncertainty principles in themselves and we may never know for sure…

There are no adjacent monuments to where Ardjachie’s stone came from, and apart from a scatter of flints found a hundred yards or so closer to the beach, other archaeological remains are down to a minimal. Its isolation is peculiar. There are however, a number of springs of water a few hundred yards away, just across the main A9 road, two of which have left their old names with us as the Cambuscurrie Well and the Fuaran nan Slainte, or fountain/spring of Healing (the modern Glenmorangie whisky gets it waters hereby!). Although we must be careful not to assign every example of prehistoric rock art with the material, the mythic association between petroglyphs and water cannot be understated, and although such an association at Ardjachie is conjectural, it cannot go unnoticed.

References:

- Brennan, Martin, The Stars and the Stones: Ancient Art and Astronomy in Ireland, Thames & Hudson: London 1983.

- Coffey, George, New Grange and other Incised Tumuli in Ireland, Hodges Figgis: Dublin 1912.

- McHardy, Stuart, A New History of the Picts, Luath: Edinburgh 2012.

- Mack, Alastair, Symbols and Pictures: The Pictish Legacy in Stone, Pinkfoot Press: Brechin 2007.

- Macnamara, Ellen, “Tain, Ardjachie Farm: Cup Markings and Incised Symbol”, inDiscovery & Excavation Scotland, 1971.

- Macnamara, Ellen, The Pictish Stones of Easter Ross, Tain & District Museum 2010.

- Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments of Scotland, Pictish Symbol Stones: A Gazetteer, Edinburgh 1999.

- Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments of Scotland, Kilmartin – Prehistoric and Early Monuments, HMSO: Edinburgh 2008.

- Scott, Douglas, The Stones of the Pictish Peninsulas of Easter Ross and the Black Isle, Historic Hilton Trust 2004.

- Twohig, Elizabeth Shee, The Megalithic Art of Western Europe, Clarendon: Oxford 1981.

- van Hoek, M.A.M., “The Rosette in British and Irish Rock Art,” in Glasgow Archaeological Journal, volume 16, 1990.

Acknowledgements: Huge thanks to Mark Taylor for use of his fine drawing in this site profile; copies of his work with Ellen Macnamara being available for sale from the Tain Museum. Many thanks to the staff at Tain Museum for their help; and many thanks again to Prof Paul Hornby in the venture to this curious old petroglyph.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.