Cup-and-Ring Stone (removed): OS Grid Reference – NS 5726 6128

Also Known as:

- Bluebell Woods

- Canmore ID 44291

- Langside Stone

Archaeology & History

Amidst where now the busy city spreads on the south-side of Glasgow, there was once an excellent multi-ringed prehistoric petroglyph to be seen. According to the official records, it was all alone – but I don’t buy that for one minute! (petroglyphs rarely occur in isolation) However, it looks as if this might have been the last of its kind in the area, betwixt where now large houses grow in the landscape of Langside and Battlefield, a few hundred yards south of the hillfort-topped Queen’s Park.

Before being noticed by archaeologists, the stone was apparently being used as a stone seat in the woods for people to sit on! It was probably a part of a larger monument, perhaps a cairn of some sort. Certainly from the sketches we have of it, it was part of a larger piece of stone and was likely to have had companions, but records seem to be silent on the matter. The most detailed description of it comes from the pen of northern antiquarian Fred Coles (1906), who gave us the following literary portrait:

“The first notice of the Stone incised with the design shown below was due to Mr W. A. Donnelly, who contributed a description and a sketch to The Glasgow Evening Times of 25th June 1902. Later, Mr Ludovic Mann, at my request, sent me certain notes he had taken of the cup-and-ring-marks. But prior to this, the Stone itself had, on the instigation of Mr Donnelly, I think, been removed from its site in the wood, and placed near one of the entrances to the new Kelvinside Museum. There I saw it and made measurements in July 1903.

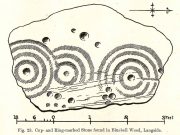

“The Bluebell Wood lies in a curving line to the west and south of Langside House, and the cup-marked Stone was at a point in the southern extremity of the wood, above and north of the river Cart. It is interesting to be able also to record that the longer axis of the Stone lay almost precisely north and South, and the opposite axis east and west.* The Stone is of a hard, whitish sandstone, a good deal weathered and rounded at the edges. It measures 4 feet 9 inches in length and 3 feet 2 inches in breadth, and varies in thickness from 2 feet 6 inches to 1 foot 7 inches. The striation of the Stone has helped to efface the cuttings which, though perfectly clear and measurable, are shallow in proportion to their width. And this feature I have endeavoured to portray in the accompanying illustration (above). Beginning at the north end of the Stone, there is one cup placed just where the outermost ring of that group touches the edge of the Stone. The ring has a groove leading towards but not into a central cup, and four other cups are placed on the two outermost rings, there being four rings in this group. The middle group consists of a central cup and three rings, flanked on the west by a row of three cups (one of which is the largest of all), and on the east by a double row of six cups, three of which are almost obliterated. This middle group is imperfectly concentric, two of its arcs running into the fourth ring of the group on the south, which has a fine deeply picked central cup. All the better-preserved rings are very nearly 1½ inches in width of cutting.

“The diameters of the outermost rings in each group are: of the north group, 1 foot 9 inches; of the middle group 1 foot 5 inches; and of the south group 1 foot 7 inches. The cups vary in diameter from 3 inches to 1½.

“Considering the extremely easily weathered nature of this Stone, and the fact that its sculptured surface has already suffered much ill-usage, its present position, near the entrance of the Art Galleries, entirely unprotected by a railing and exposed to all sorts of abuse by casual passers-by as well as the weather, is not a fit and proper place for a Stone of such interest.”

A few years after this, the local historian Ludovic MacLellan Mann (1930) wrote a piece for the Glasgow Herald, in which he thought that both this and another carving in the area,

“commemorate chiefly…an eclipse of the sun seen in Glasgow district in the year 2983 BC, at three o’ clock in the afternoon of the sixth day after the Spring Equinox.”

A fascinating idea… Mann was intrigued by the theory that petroglyphs represented astronomical events or maps of the skies – and we know from cultures elsewhere in the world that some carvings had such a function; but it’s not integral to all carvings by any means.

A fascinating idea… Mann was intrigued by the theory that petroglyphs represented astronomical events or maps of the skies – and we know from cultures elsewhere in the world that some carvings had such a function; but it’s not integral to all carvings by any means.

The stone was included in Ron Morris’ (1981) survey, merely echoing the description of Fred Coles, adding nothing more. And so it seems that the carving is still in the museum somewhere. Canmore has it listed as “Accession no: 02-78”. Does anyone know of its present situation? Can anyone get a photo so we can give it a more fitting site profile? It looked a damn good carving! And, if anyone lives nearby, I note that there are small patches of the old woodland still visible on GoogleEarth: therein, perhaps, a diligent explorer may just find another carving….

References:

- Coles, Fred, “Notices of Standing Stones, Cists and Hitherto Unrecorded Cup-and-Ring Marks in Various Localities,” in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 40, Edinburgh 1906.

- Donnelly, W.A., “Letter”, Glasgow Evening Times, 25 June, 1902.

- Mann, Ludovic MacLellan, “The Eclipse in 2983 B.C. – Discovery near Glasgow,” in Glasgow Herald, 17.09.1930.

-

Morris, Ronald W.B., “The Cup-and-Ring Marks and Similar Sculptures of South-West Scotland,” in Transactions of the Ancient Monuments Society, volume 14, 1967.

-

Morris, Ronald W.B., The Prehistoric Rock Art of Southern Scotland, BAR: Oxford 1981.

-

Morris, Ronald W.B. & Bailey, Douglas C., “The Cup-and-Ring Marks and Similar Sculptures of Southwestern Scotland: A Survey,” in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 98, 1966.

-

Small, Sam, Greater Glasgow: An Illustrated Architectural Guide, RIAS: Edinburgh 2008.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: Huge thanks to beautiful Aisha for putting me up.

* Although Coles did note how its earlier use as a stone seat probably negates his axial measurements.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian