Crosses: OS Grid Reference – SD 7326 3616

Also Known as:

- Paulinus Crosses

Dead easy to find. Get to the centre of Whalley and walk into the churchyard. Don’t confuse it with the ruins of the old abbey, or you won’t find the place!

Archaeology & History

I here wish to draw your attention to the three standing crosses in the churchyard (the crosses do not stand in their original positions having being ‘thrown down’ during the Commonwealth and used amongst other things as farm gate-posts):

1) THE EASTERMOST CROSS (Taylor ‘C’): Standing opposite the chancel door (Priest’s Door, early 13th century retaining the original ironwork and bronze head knocker) is a much-worn cross shaft that only under certain lighting conditions that can any decoration is made out. It has scrollwork as pat of its ornament and a pelleted border. Two figures, heads surrounded by halos, can be made out just above the shaft centre. The head of the cross is not original but of the late 14th century. The cross originally stood over 11ft in height (see drawing reconstruction). Fragments of this cross are built into the fabric of the church, the top section of the shaft and parts of the cross head are held in Blackburn Museum. One fragment can be made out in the outside Chancel wall displaying the pelleted border and some scrollwork. Another fragment is built into the back wall of the Sedilia and is in good condition. A further fragment is built into the back wall of the Bishops Throne, last stall, south side, east adjacent the Sanctuary.

The shaft is set in a broken oblong base that one may have held two or more shafts in the form of a ‘Calvary’.

2) THE WESTERMOST CROSS (Taylor ‘A’): Originally panelled crosses of this type were brightly painted in red, yellow, green, blue and white. All four sides are decorated but only the east face survives clearly enough to be made out. The shaft was divided into seven panels with roll-mouldings running along each of the panels, of which only six now exist (part of the upper panel, displaying the hallowed head of a figure and cross arm are held by Blackburn Museum). The two lowest panels and the top panel contain geometric and interlace patterns. Halfway is a sculptured panel containing a hallowed human figure, arms akimbo (raised as if giving a blessing). Either side of the figure are two serpents with open mouths. This design is repeated on the side face of the shaft along with two interlace panels. Above the figure panel is one depicting the figure of a bird (an eagle or pelican in her piety?). The lower panel shows that of a beast (a dog or a lion?).

Crosses 1 and 2 clearly show Hiberno-Norse influences, so named after the second and third generation Irish Norwegians who settled Lancashire in the 10th century whose artistic culture became dominant.

3) THE CROSS OPPOSITE THE PORCH (Taylor ‘B’): This magnificent cross is in a fair state of preservation, although a portion of the upper shaft and three arms of the head are missing. Originally it would have stood at around 10ft in height and is the oldest of the crosses being no later than the late 10th century. The central cross shaft measures approximately 2.2m high and is socketed into a square base stone carved with dog-tooth decoration. It is rectangular in cross section and tapers towards the top where it has been broken. A piece of the shaft about 0.75m in length is missing. All four sides of the shaft depict well-preserved late 10th century decoration comprising foliated scrollwork. The principal ornamentation is on the east and west faces and consists of a central rounded shaft or pole rising from the apex of a gable. At the top of the shaft are the mutilated remains of the carved central boss of the cross head.

The central rounded column forms the axis mundi (cosmic axis, world pillar), being a ubiquitous symbol that crosses human cultures. The image expresses a point of connection between the heavens and earth where the four compass directions meet. At this point travel and correspondence is made between higher and lower realms. Communication from lower realms may ascend to higher ones and blessings from higher realms may descend to lower ones and be disseminated to all. The spot functions as the omphalos (navel), the world’s point of beginning.

The axis mundi image appears in every region of the world and takes many forms: a hill or mountain (Pendle), a tree (Tree of Life, World Ash Tree, etc), a vine, a ladder (Jacob’s Ladder), a stone monolith, a maypole, Sufi whirling, etc. The foliated swirls represent interactive movement along the axis – transmission, unity within multiplicity.

The axis mundi concept has its origins in Indo-European shamanism, and a universally told story is that of the healer traversing the axis mundi to bring back knowledge (benefits/blessings, etc) from the ‘other world’. The Sufi concept of baraka and the Hindu mystical concept of akasha are akin to this.

All three crosses had cross heads of four arms of equal length, each widening at the outer end in an axe shape so that their rims nearly form a circle.

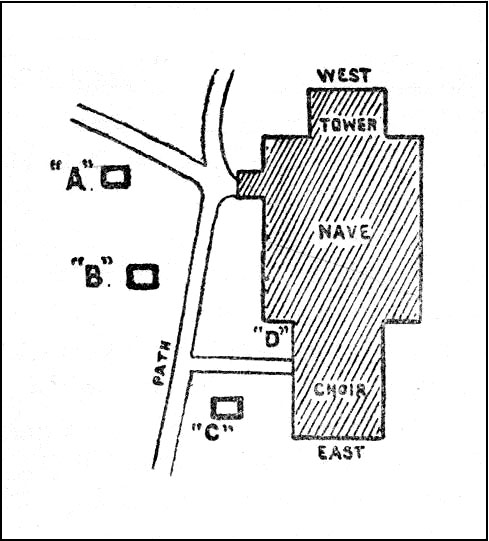

Editor’s Note: Henry Taylor (1904) described the “remains of other pre-Norman crosses” at the point marked ‘D’ on his map of the church, adding:

“The Bishop of Bristol thus describes the fragments of other crosses at Whalley: ‘A pretty and delicate fragment forms part of the back of the sedilia; there is at least one piece in the south wall of the chancel, outside, and there are fragments lying on the ground. One of these, showing a system of oval buckles, as it were, with straps through them, closely resembles a stone found — but now lost — at Prestbury…”

Folklore

Taylor mentions how the Whalley crosses were long known as the Paulinus Crosses, “who is said to have been made Archbishop of York in the year 627, and who, it is alleged, preached and baptised in the wild districts far removed from that capital, even in such remote places as Whalley… His name is also attached to an ancient cross…on Longridge Fell.”

References:

- Taylor, Henry, The Ancient Crosses and Holy Wells of Lancashire, Sherratt & Hughes: Manchester 1906.

- Whitaker, Thomas Dunham, An History of the Original Parish of Whalley and Honor of Clitheroe, Nichols, Son & Bentley: London 1818.

© John Dixon, 2010

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.