Holy Well: OS Grid Reference – SD 93096 56992

Also Known as:

- Helen’s Well

On the A65 road from Skipton to Gargrave, just at the eastern end of Gargrave, take the small Eshton Road running north over the canal. Go through Eshton itself, making sure you bear right at the small road a few hundred yards past the old village. Keep your eyes peeled a few hundred yards down as you hit the river bridge and stop here. Just 50 yards before this is a parking spot where some Water Board building stands. Walk back up the road barely 20 yards and you’ll see, right by the roadside, a small clear pool on your left, encircled by trees. Go through the little stile here and you’re right by the water’s side!

Archaeology & History

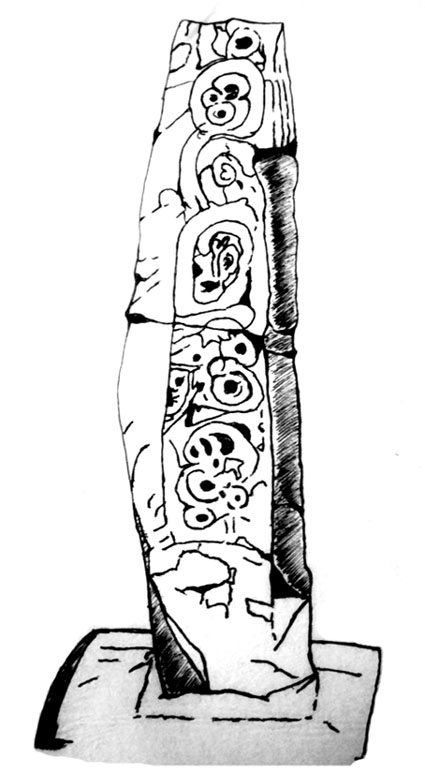

This is actually a listed monument (unusual for wells up North!), just off the roadside between Nappa Bridge and Eshton Hall. Two or three old stone heads (deemed to be ‘Celtic’ in age and origin, though I had my doubts) have recently been stolen from this holy pool close to where the water emerges from the ground, just beneath the surface. You can see where the water bubbles up strongly from the Earth when you visit here, forming the small pool in front of it, around which at certain times of year people still attach ‘memaws’ (an old word for ritual ‘offerings’) on the small shrubs. If you drink from here, just where the water bubbles up (careful not to fall in!), it’s freezing — but tastes absolutely gorgeous! And better than any tap-water you’ll ever drink!

Mentioned briefly in Mr Hope’s (1893) fine early survey; the earliest description of this site in relation to the mythic ‘Helen’ dates from 1429, where T.D. Whitaker (1878) described the dedication to an adjacent chapel, long gone. Whitaker’s wrote:

“…One of the most copious springs in the kingdom, St. Helen’s Well fills at its source a circular basin twenty feet in circumference, from the whole bottom of which it boils up without any visible augmentation in the wettest seasons, or diminution in the driest. In hot weather the exhalations from its surface are very conspicuous. But the most remarkable circumstance about this spring is that, with no petrifying quality in its own basin, after a course of about two hundred yards over a common pebbly channel, during which it receives no visible accession from any other source, it petrifies strongly where it is precipitated down a steep descent into the brook. To this well anciently belonged a chapel, with the same dedication; for in the year 1429, a commission relating to the manor of Flasby sat “in capella beate Elene de Essheton; and on the opposite side of the road to the spring is a close called the Chapel Field. This was probably not unendowed, for I met with certain lands in Areton, anciently called Seynt Helen Lands.”

When the old countryman Halliwell Sutcliffe (1939) talked of this healing spring, his tone was more in keeping with the ways of local folk. Sutcliffe loved the hills and dales and old places to such an extent that they were a part of his very bones. And this comes through when he mentions this site. Telling where to find the waters, he continued:

“Its sanctuary is guarded by a low mossy wall. Neglected for years out of mind, it retains still clear traces of what it was in older times. An unfailing spring comes softly up among stones carved with heart-whole joy in chiselling. Scattered now, these stones were once in orderly array about what is not a well, in the usual sense, but rather a wide rock-pool, deep here and shallow there, with little trees that murmur in the breeze above. Give yourself to this place, frankly and with the simplicity is asks. It does not preach or scold, or rustle with the threat of unguessed ambushes among the grassy margin. Out of its inmost heart it gives you all it knows of life.”

In the field across the road where the chapel was said to have been, we find another stone-lined fresh-water well bubbling from the ground into a stone trough (at grid-ref SD 93118 56958). The waters here are also good and refreshing. But whether this fine water source had any tales told of it, or curative properties (it will have done), history has sadly betrayed its voice.

Folklore

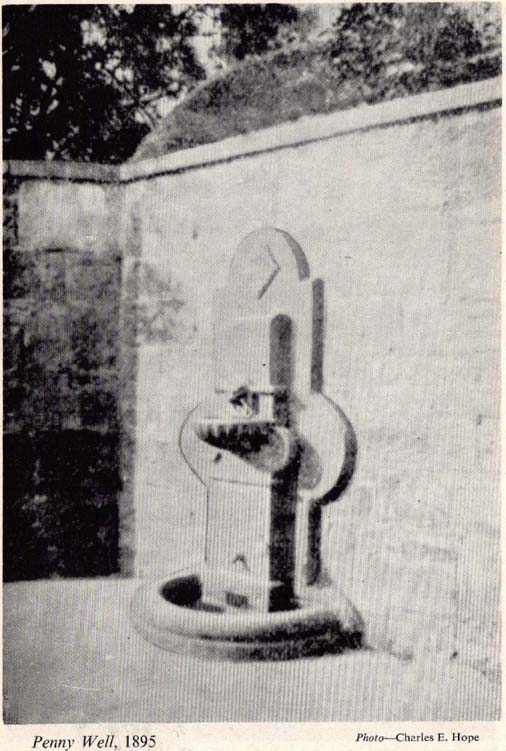

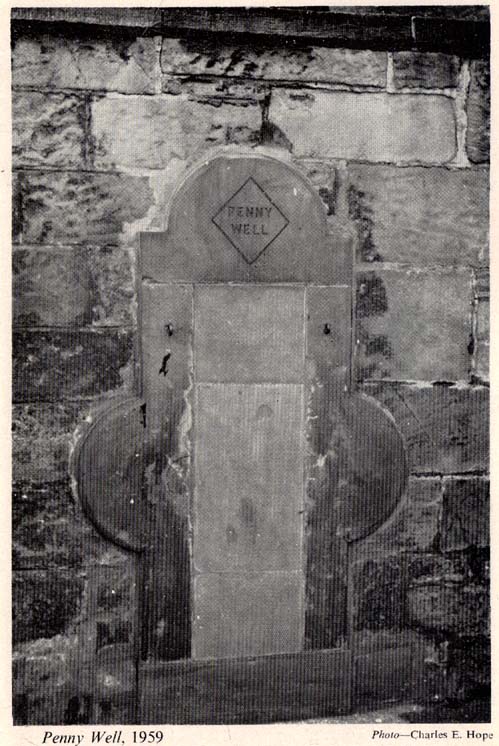

The waters here have long been reputed as medicinal. R.C. Hope (1893) said “this well was a certain cure for sore and weak eyes.” Whitaker and others told there to be hangings of rags and other offerings (known in Yorkshire as ‘memaws’). Sutcliffe described,

“The pilgrims coming with their sores, of body and soul… The Well heard tales that were foul with infamies of the world beyond its sanctuary. Men came with blood-guilt on their hands, and in their souls a blackness and a terror. Women knelt here in bleak extremity of shame. The Well heard all, and from its own unsullied depths sent up the waters of great healing. And the little chant of victory began to stir about the pilgrims’ hearts…and afterwards the chant gained in volume. It seemed to them that they were marching side by side with countless, lusty warriors who aforetime had battled for the foothold up the hills. And, after that, a peace unbelievable, and the quiet music of Helen’s Well, as her waters ran to bless the farmward lands below. All this is there for you to understand today, if you will let the Well explain the richness of her heritage, the abiding mystery of her power to solace and to heal.”

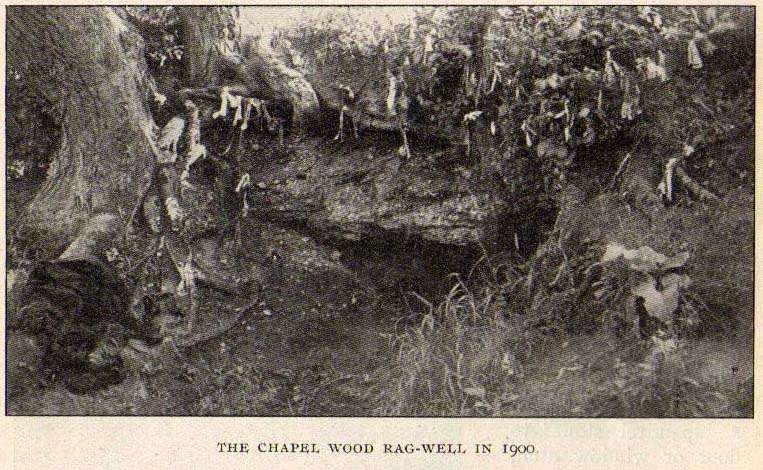

And so it is with many old springs… The rite of memaws enacted at St. Helen’s Well is a truly archaic one: whereby a person bringing a cloth or stone or coin — using basic principles of sympathetic magick — asks the spirit of the waters to cleanse them of their illness and pass it to the rags that are tied to the adjacent tree; or perhaps some wish, or desire, or fortune, be given in exchange for a coin or something if personal value. The waters must then be drunk, or immerse yourself into the freezing pool; and if the person leaving such offerings is truly sincere in their requests, the spirit of the water may indeed act for the benefit of those concerned.

Such memaws at St. Helen’s Well are still left by local people and, unfortunately, some of those idiotic plastic pagans, who actually visit here and tie pieces of artificial material to the hawthorn and other trees, which actually pollutes the Earth and kills the spirit here. Whilst the intent may be good, please, if you’re gonna leave offerings here, make sure that the rags you leave are totally biodegradable. The magical effectiveness of your intent is almost worthless if the material left is toxic to the environment and will certainly have a wholly negative effect on the spirit of the place here. Please consider this to ensure the sacred nature of this site.

…to be continued…

References:

- Hope, Robert Charles, Legendary Lore of the Holy Wells of England, Elliott Stock: London 1893.

- Smith, A.H., The Place-Names of the West Riding of Yorkshire – volume 6, Cambridge University Press 1961.

- Sutcliffe, Halliwell, The Striding Dales, Frederick Warne: London 1939.

- Whelan, Edna, The Magic and Mystery of Holy Wells, Capall Bann: Chieveley 2001.

- Whelan, Edna & Taylor, Ian, Yorkshire Holy Wells and Sacred Springs, Northern Lights: Dunnington 1989.

- Whitaker, T.D., The History and Antiquities of the Deanery of Craven, Joseph Dodgson: Leeds 1878.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.