Holy Well: OS Grid Reference – NT 27322 68365

Also Known as:

- Balm Well

- Canmore ID 152718

- Oily Well

- Oyly Well

- St. Katherine’s Well

Take the A701 road from the east end of Princes Street south—down North Bridge, South Bridge, Nicolson Street, onto Liberton Road and then Liberton Gardens—towards Penicuik. 3¾ miles along, in the parish of Liberton itself, where the A701 is called Howden Hall Road, keep your eyes peeled for the turning into the Toby Carvery on your left. Park up and walk across the grass and look behind the trees ahead of you (if you can’t find it, ask the people in the pub). .

Archaeology & History

Located south of Liberton village—a few hundred yards west of the long-gone chapel erected by St. Margaret in honour of St. Catherine—this famous holy well is now in the grounds of a public house and is easily accessed. It has been described by many historians through the centuries, from Matthew Mackaile’s (1664) short work to more recent tourist guides. When the local historian George Good (1893) told about it, local lore still spoke of the old church. “These lands,” he wrote,

“belonged to a very ancient chapel dedicated to St. Catherine, which stood with its burying-ground near the modern mansion of St. Catherine’s. All trace of this chapel has disappeared, but at the end of last century its ruins were still extant. It was reputed to be the most ancient place of worship in the parish, and the ground around the chapel was consecrated for burials. Hither came annually in solemn procession the nuns from the Convent of Sciennes, a foundation due to the piety of one of the St. Clairs of Rosslyn, who may possibly have also been connected with the origin of the Chapel of St. Catherine.”

Its relationship with the world-famous Roslyn Chapel, less than 4 miles to the south, remains (to my knowledge) unproven, but it’s an association that would not be unlikely. This aside, St Catherine’s Well has a long history. Described in Hector Boece’s Latin text Scotorum Historia (1526), we have one John Bellenden to thanks for a wonderful translation into early english under the title of The History and Chronicles of Scotland in 1536. Herein one of the later editions we read, in that quaint old dyslexia:

“Nocht two miles fra Edinburgh is ane fontane dedicat to Sanct Katrine, quhair sternis of oulie springs ithandlie with sic abundance that howbeit the samin be gaderit away, it springis incontinent with gret abundance. This fontane rais throw ane drop of Sanct Katrine’s oulie, quhilk was brocht out of Monte Sinai, fra her sepulture, to Sanct Margaret, the blissit Quene of Scotland. Als sone as Sanct Margaret saw the oulie spring ithandlie, by divine miracle, in the said place, sche gart big ane chapell thair in the hounour of Sanct Katrine. This oulie has anr singulare virteu agains all maner of kankir and skawis.”

In the middle of the 17th century, its medicinal virtues were brought to the attention of the surgeon Matthew Mackaile who, in 1664, wrote:

“In the paroch of Libberton, the church whereof lyeth two miles southward from Edinburgh, there is a well at the Chapel of St. Catherine’s, which is distant from the church about a quarter of a mile, and is situate toward the south-west, whose profundity equaleth the length of a pike, and is always replete with water, and at the bottom of it there remaineth a great quantity of black oyl in some veins of the earth. His Majesty King James VI, the first monarch of Great Britain, of blessed memory, had such a great estimation of this rare well, that when he returned from England to visit his ancient kingdom of Scotland in anno 1617, he went in person to see it, and ordered that it should be built with stones from the bottom to the top, and that a door and a pair of stairs should be made for it, that men might have the more easy access into its bottom for getting of the oyl. This royal command being obeyed, the well was adorned and preserved until the year 1650, when that execrable regicide and usurper, Oliver Cromwell, with his rebellious and sacrilegious complices, did invade this kingdom, and not only defaced such rare and ancient monuments of Nature’s handiwork, but also the synagogues of the God of nature.”

This historical appraisal has been echoed by other writers and is very probably accurate. Some years after Cromwell and his murderers had desecrated the land and people in this area, the well was again repaired to its former condition and slowly, quietly, people began traditionally using the site for ritual and healing once more. But over the next two hundred years, probably through religious persecution by the Church, the site was used less and less and, by the time Thomas Muir (1861) visited and wrote about it, the well-house had become “dilapidated”. A few years later when the holy wells writer J.R. Walker (1883) visited the place, he found that not only was it still,

“celebrated for the cure of cutaneous diseases, (but) it is still visited for its medicinal virtues”; and was “now carefully protected and looked after.”

In James Begg’s (1845) account of the well for the Statistical Account, he told:

“At St. Catherine’s is a well which contains a quantity of mineral oil or petroleum, obtained most probably from the spring flowing over some portion of the coal beds. This bitumous matter floats copiously on the surface of the water, and is also partially dissolved in it. The spring is reckoned medicinal by the country people, and may have some slight efficacy in cutaneous eruptions…

“At St Catherine’s, there is the famous well, before alluded to, anciently called the Balm Well. Black oily substances constantly float on the surface of the water. However many you remove they still appear to reside in this well, and it was much frequented by persons afflicted with cutaneous complaints. The nuns of the Sheens made an annual procession to it in honour of St Catharine. King James VI visited it in 1617, and ordered it to be properly enclosed and provided with a door and staircase, but it was destroyed and filled up by the soldiers of Cromwell in 1650. It has again been opened and repaired, and is now in a good state of preservation.”

The “nuns of the Sheens” who made the annual pilgrimage here were the nuns of St. Catherine’s of Sienna, in Italy! This crazy-sound journey is more than one thousand miles long and its nature and origin needs exploring in greater depth. A number of curiously-named ‘Caty’ wells seem to relate to this incredible venture, whose scope will hopefully be covered in a future essay.

It would have been more than just the healing properties of the oily waters that called the nuns across their incredible journey, but they would, no doubt, have been of considerable mythic importance. All of the early writers comment about it and seem confident in its abilities. As the Liberton historian George Good (1893) said,

“…there can be little doubt that its waters had a healing tendency. Oils when rubbed on the skin have often been found to produce most beneficial results in skin diseases. The tarry substance or petroleum mixture discovered in this spot was no doubt due to the presence of the coal or shale strata of the district. The existence of the oil-works at Straiton and elsewhere cannot fail to throw a light upon the history and peculiarities of the so-called Balm Well of St. Catherine’s, which even yet has an occasional visitor.”

This oily substance was examined for medical potential by Dr. George Wilson in the mid-19th century, who found:

“The water from St Katherine’s Well contains after filtration, in each imperial gallon, grs. 28.11 of solid matter, of which grs. 8.45 consist of soluble sulphates and chlorides of the earths and alkalies, and grs. 19.66 of insoluble calcareaous carbonates.”

I am not aware of any modern accounts of cures attached to St Catherine’s waters, but have little doubt that some people will have found it useful….

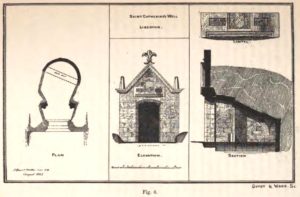

The architecture of the small well-house covering the waters would seem insubstantial, but the Royal Commission (1929) account told:

“The well is housed within a tiny vaulted structure. The Renaissance front is relatively modern, but it contains a door lintel, probably quite unconnected with the structure, on which is inscribed the date 1563 within recessed panels flanking a central panel, which contains a shield flanked by the initials A.P. The shield bears a saltire, in the sinister quarter of which is a Latin cross placed horizontally, i.e., with the shaft towards the fess point (? a merchant’s mark); the upper quarter contains a much worn object resembling a broad arrow, point uppermost.”

The iron-clad door is locked, as the visitor will see. Please enquire at the hotel regarding it being opened to look inside. Upon our visit here in June 2017, the waters, as in J.R. Walker’s (1883) day, were still bubbling up and were quite high, but it looked as if the inside needed cleaning. For a change, we didn’t drink the water…..

Folklore

Although various writers have posited that the oily waters are probably due related to the nearby coalfields, legend tells otherwise:

“It owes its origin, it is said, to a miracle in this manner: St. Katherine had a commission from St. Margaret, consort of Malcolm Canmore, to bring a quantity of oil from Mount Sinai. In this very place, she happened, by some accident or other, to lose a few drops of it, and, on her earnest supplication, the well appeared as just now described.” (Thomas Whyte 1792)

References:

- Banks, M. MacLeod, British Calendar Customs: Scotland – volume 1, Folklore Society: London 1937.

- Begg, James, “Parish of Liberton“, in New Statistical Account of Scotland – volume 1: Edinburgh, William Blackwood: Edinburgh 1845.

- Bellenden, John (trans.), The History and Chronicles of Scotland, Written in Latin by Hector Boece, W. & C. Tait: Edinburgh 1821.

- Bennett, Paul, Ancient and Holy Wells of Edinburgh, TNA: Stirling 2017

- Geddie, John, The Fringes of Edinburgh, W. & R. Chambers: Edinburgh 1926.

- Good, George, Liberton in Ancient and Modern Times, Andrew Elliot: Edinburgh 1893.

- Mackaile, Matthew, The Oyly Well; or a Topographico-Spagyrical Description of the Oyly-Well, at St. Catharines Chappel in the Paroch of Libberton, Robert Brown: Edinburgh 1664.

- MacKinlay, James M., Folklore of Scottish Lochs and Springs, William Hodge: Glasgow 1893.

- Morris, Ruth & Frank, Scottish Healing Wells, Alethea: Sandy 1982.

- Muir, Thomas S., Characteristics of Old Church Architecture, in the Mainland and Western Isles of Scotland, Edmonston & Douglas: Edinburgh 1861.

- Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments of Scotland, Inventory of Monuments and Constructions in the Counties of Midlothian and West Lothian, HMSO: Edinburgh 1929.

- Walker, J. Russel, “Holy Wells’ in Scotland,” in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, volume 17, 1883.

- Watson, W.N.B., “The Balm-Well of St Catherine, Liberton,” in Book of the Old Edinburgh Club, volume 33, 1972.

- Whyte, Thomas, “An Account of the Parish of Liberton in Midlothian, or County of Edinburgh,” in Archaeologica Scotica, volume 1, 1792.

- Wilson, Daniel, Memorials of Edinburgh in the Olden Times – 2 volumes, Edinburgh 1891.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.