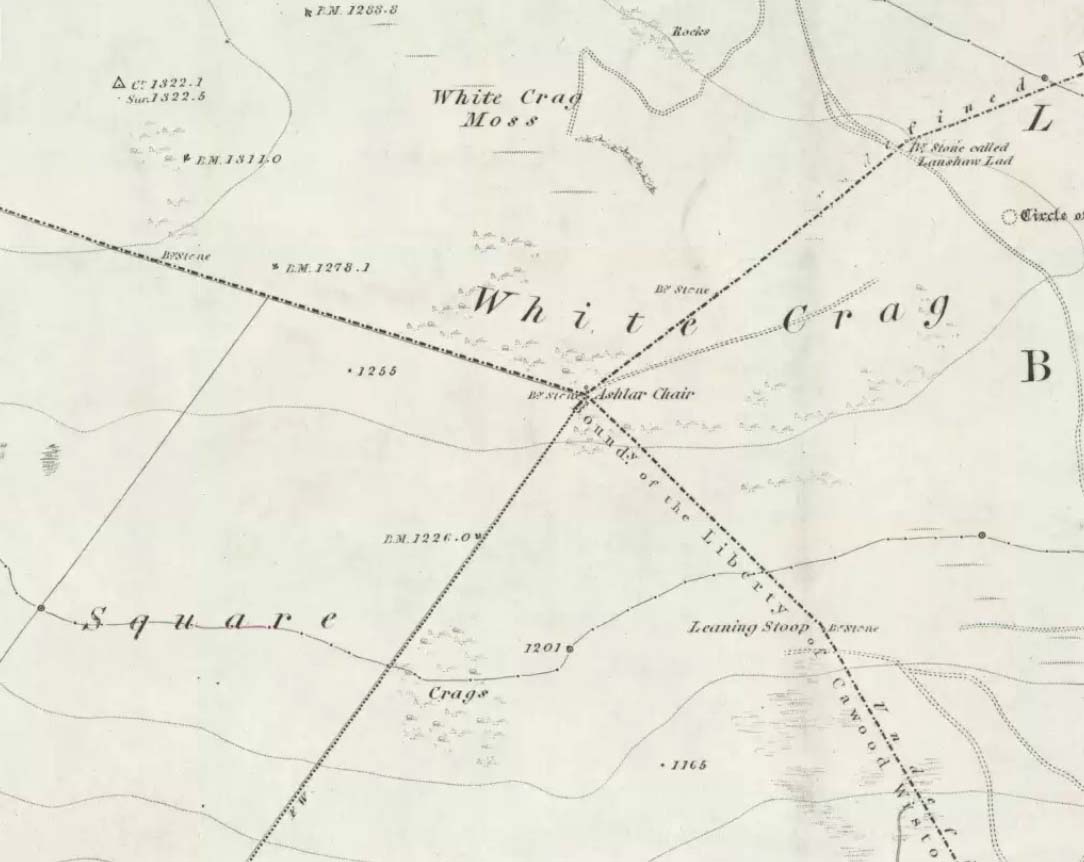

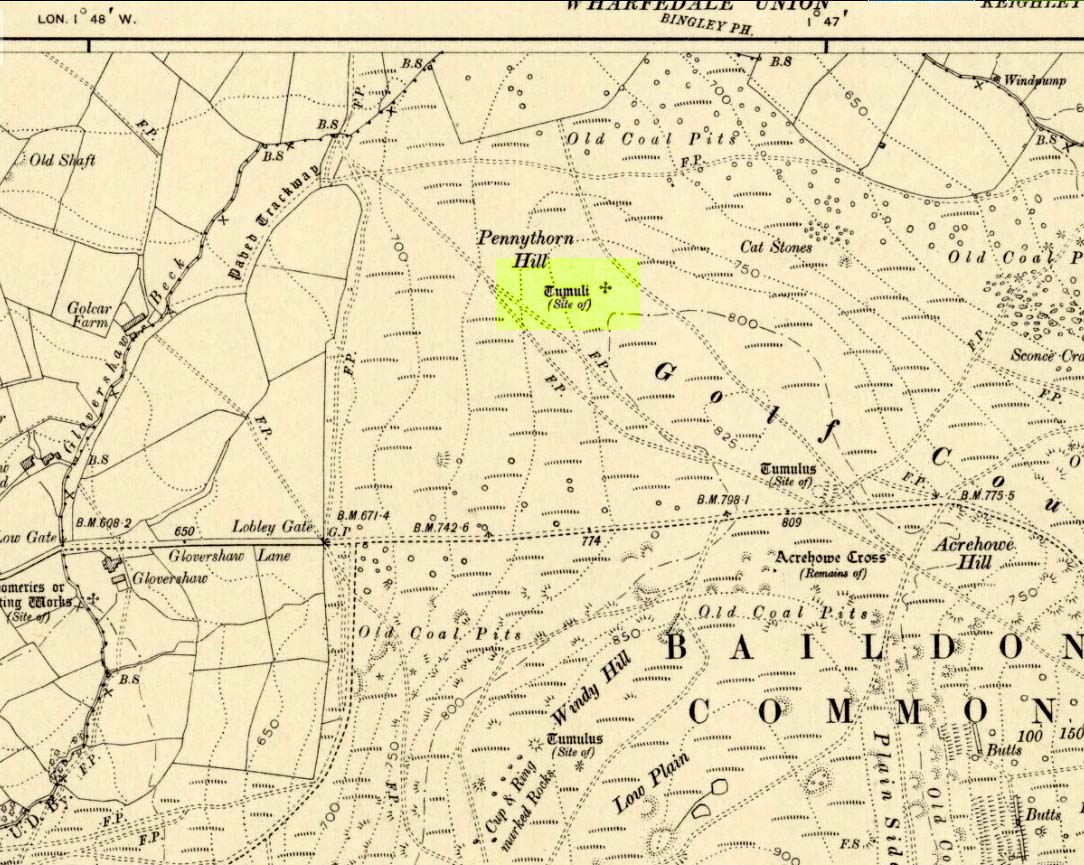

Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – SE 13724 40096

Also Known as:

- Carving no.22 (Hedges)

Whether you come via Shipley Glen or Baildon, head for the Dobrudden caravan park on the western edge of Baildon Hill. As you get to the entrance of the caravan site, turn right and walk along the outer walling of the caravan site, up and around for less than 100 yards. Keep your eyes peeled for the upright stone against the outer walling (the famous Dobrudden Cup-and-Ring Stone), and just 10 yards away, laid flat in the grasses, you’ll see this small cup-and-ring stone!

Archaeology & History

Found just a few yards from the well-known Dobrudden Carving that stands up against the wall, this small flat level stone, slowly again being encroached by Earth’s skin, is found on the edge of the High Plain, whereon the usual conjunction of prehistoric tombs and cup-and-rings is found once again. Whether this carving ever had its own cairn or funerary monument is now hard to say for sure; and the excessive erosion of modern humans is slowly eradicating the landscape all round here.

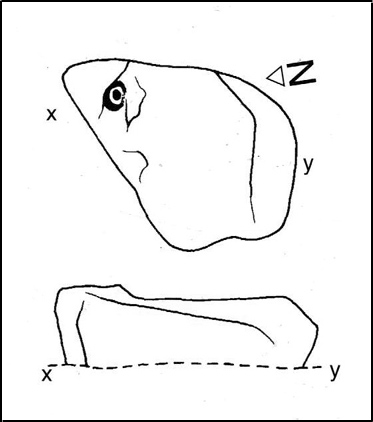

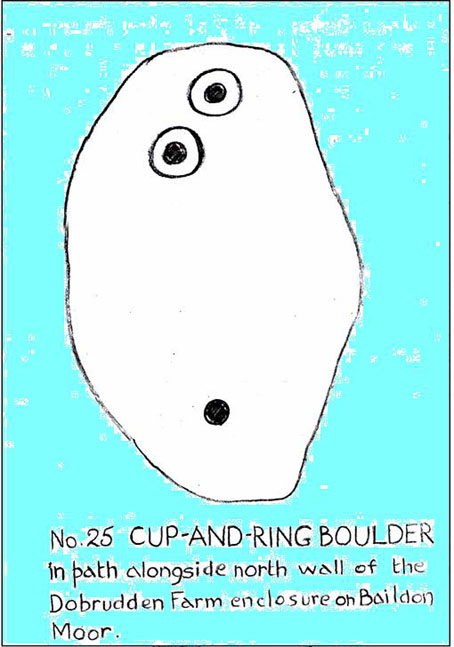

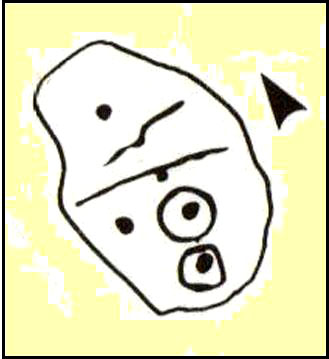

Consisting of two cup-and-rings (with very deep cupmarks in the centres), there are also what seem like artificially carved lines or grooves running across the stone. It was first described in a short article in the Cartwright Hall Archaeology Group Bulletin (Jackson 1956)*, found lying “in the path alongside the north wall of the Dobrudden Farm enclosure.” It seems like stone may have been covered over until some local work on Dobrudden unearthed it in the latter half of the 20th century. There’s also an intriguing note told by a local man called Jack Taylor, which Jackson narrated, saying how he,

“always held the opinion that the rings were not contemporary with the cups, and went so far as to suggest that they had been carved within living memory by someone anxious to ‘improve’ the boulder.”

This might be the case, as there is another carving not far away near the top of Baildon Hill that certainly seems to have been done in the 20th century. And one of the two surrounding rings on this stone does appear to have a more recent look to it than the other. However, we must consider that the covering soil has kept the carved rings in such good condition. (There are examples of petroglyphs throughout the world where certain carved elements were added at later times by countless aboriginal tribes.)

Like all of these carvings, to get an accurate picture of the true original we must visit them in all weathers all through the year, to see how differing seasons express the petroglyph. For we can see on some images we have of this carving a number of features that aren’t on the drawings of either Jackson (1956) or Hedges (1986): whether the rings surrounding the cups are ancient or not, there is a definite carved line nearly linking them together; and at least one faint line stretches down from one of the rings. We need to visit the carving again to see if such features show up with greater clarity when lighting conditions are better.

References:

- Baildon, W. Paley, Baildon and the Baildons – parts 1-15, Adelphi: London 1913-1926.

- Bennett, Paul, Megalithic Ramblings between Ilkley and Baildon, unpublished: Shipley 1982.

- Boughey, Keith & Vickerman, E.A., Prehistoric Rock Art of the West Riding, WYAS: Leeds 2003.

- Hedges, John, The Carved Rocks on Rombald’s Moor, WYMCC: Wakefield 1986.

- Jackson, Sidney, “Another Cup-and-Ring Boulder,” in Bradford Cartwright Hall Archaeology Group Bulletin, 1:13, 1956.

* Boughey & Vickerman (2003) cited W. P. Baildon’s magnum opus (1913) as the first to describe this stone, but this is untrue (there’s certainly no mention nor illustration of it in my editions of the Baildon volumes).

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.