Cairn: OS Grid Reference — SE 14053 44541

Also Known as:

- Great Apronful of Stones

Various routes to this giant tomb, which happens to be a way off the roads (thankfully!). Probably the easiest way is from the Menston-side: up Moor Lane, turn left at the end, go 200 yards and take the track onto the moor. Just keep walking. If you hit the rock-outcrop nearly a mile on, you’ve gone past your target. Turn back for about 400 yards and walk (south) into the heather. You’re damn close!

Archaeology & History

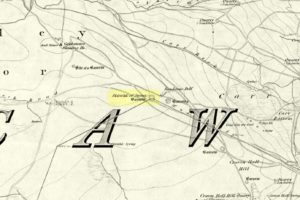

Due north of the Skirtful Spring water source, this is one of Ilkley Moor’s major prehistoric sites: ‘major’ for a number of reasons – not least of which is the size of the thing! Although getting somewhat overgrown these days as more of the heathlands encroach the mass of rocks that constitute the central ‘tomb’, it is still a formidable heap. Another reason this site is of importance is its position in the landscape: it can be seen as the peak or ‘nipple’ on the landscape from considerable distances north, south and east of here, rising up on the horizon and catching the eye from many miles away. This was obviously quite a deliberate function of the site when it was first constructed – thought to be in the Bronze or Iron Age period (sadly we have no decent excavation here to tell us just when it was made). Another reason for its importance is its position relative to a once huge prehistoric graveyard immediately east. And right next to it we also find a curious circular monument that has never been properly excavated, whose function is unknown. It is also the seeming focal point of at least one, though possibly three prehistoric trackways: one of which goes right past it, though swerves on its southern edge quite deliberately so as to not touch the monument. This trackway appears to have been a ceremonial ‘road of the dead,’ along which our ancestors were carried, resting for some reason at the nearby Roms Law, or Grubstones Circle, a few hundred yards to the west.

Wrongly ascribed as a “round barrow” by archaeologist Tim Darvill (1988), the Great Skirtful cairn was named in boundary changes made in 1733, where one Richard Barret of Hawksworth told that the site was “never heard go by any other name than Skirtfull of Stones.”

In 1901 there was an article in the local ‘Shipley Express‘ newspaper — and repeated in Mr Laurence’s (1991) fine History of Menston and Hawksworth — which gave the following details:

“Mr Turner led the way across Burley Moor to the Great Skirtful of Stones, a huge cairn of small boulders, nearly a hundred tons on a heap, although for centuries loads have been taken away to mend the trackways across the moor… The centre of the cairn is now hollow, as it was explored many years ago, and from the middle human bones were taken and submitted to Canon Greenwell and other archaeologists” – though I have found little in Greenwell’s works that adequately describe the finds here. Near the centre of the giant cairn is a large stone, of more recent centuries, which once stood upright and upon which is etched the words, “This is Rumbles Law.” The Shipley Express article goes on: “Mr Turner explained that ‘law’ was always used in the British sense for a hill, and Rumbles Hill, or cairn, was a conspicuous boundary mark for many centuries. He had found in the Burley Manor Rolls, two centuries back, that on Rogation Day, when the boundaries were beaten by the inhabitants, they met on this hill, and describing their boundaries, they concluded the nominy by joining in the words, “This is Rumbles Law.””

Several other giant cairns like this used to be visible on the moors, but over the years poor archaeological management has led to their gradual decline (and in editing this site profile in 2016, have to report that poor archaeological and moorland management is eating into and gradually diminishing this monument to this day). We still have the Great Skirtful’s little brother, the Little Skirtful of Stones, a half-mile north of here. The very depleted remains of the once-huge Nixon’s Station giant cairn can still be seen (just!) at the very top of Ilkley Moor 1½ miles (2.65km) west.* And we have the pairing of the giant round cairn and long cairn a few miles west on Bradley Moor, near Skipton. The tradition of such giant tombs on these hills was obviously an important one to our ancestors.

Folklore

We find a curious entry in the diaries of the Leeds historian Ralph Thoresby, in the year 1702, which seems to describe the Great Skirtful of Stones, adding a rather odd bit of folklore. (if it isn’t the Great Skirtful, we’re at a loss to account for the place described.) Mr Thoresby told how he and Sir Walter Hawksworth went for a walk on Hawksworth’s land and said how,

“he showed us a monumental heap of stones, in memory of three Scotch boys slain there by lightning, in his grandfather’s, Sir Richard Hawksworth’s time, as an old man attested to Sir Walter, who being then twelve years of age helped to lead the stones.”

As far as I’m aware, this old story of the three Scottish boys is described nowhere else.

Like many giant cairns, the Great Skirtful has a familiar creation myth to account for its appearance. In one version we hear that it was made when the local giant, Rombald (who lived on this moor) and his un-named wife were quarrelling and she dropped a few stones she was carrying in her apron. A variation swaps Rombald’s wife with the devil, who also, carelessly, let the mass of stones drop from his own apron to create the ancient cairn we still see today.

According to Jessica Lofthouse’s North Country Folklore (1976), a Norse giant by the name of Rawmr, “fell fighting against the Britons of Elmet and is buried, they say, on Hawksworth Moor” – i.e., the southeastern section of Rombald’s Moor, very probably at the Great Skirtful of Stones. I’ve yet to explore the history and etymology of the name Rawmr…

…to be continued…

References:

- Bennett, Paul, The Old Stones of Elmet, Capall Bann: Chieveley 2001.

- Cowling, Eric T., Rombald’s Way, William Walker: Otley 1946.

- Darvill, Timothy, Ancient Britain, AA: Basingstoke 1988.

- Laurence, Alastair, A History of Menston and Hawksworth, Smith Settle: Otley 1991.

* Whoever is/was supposed to be responsible for the care of the Nixon’s Station giant cairn monument should be taken to task as it’s been virtually obliterated since when I first came here 30 years ago. Which useless local archaeologist and/or council official is responsible for its destruction? Who allowed it to happen? Why are Ilkley Moor’s prehistoric monument’s being so badly looked after by those who are paid to ensure their maintenance? Are their heads up their arses, in the sand, or—don’t tell me—the prawn sandwiches are to blame!?

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian