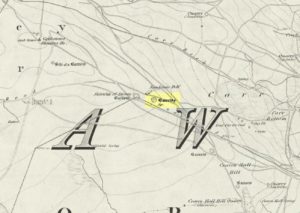

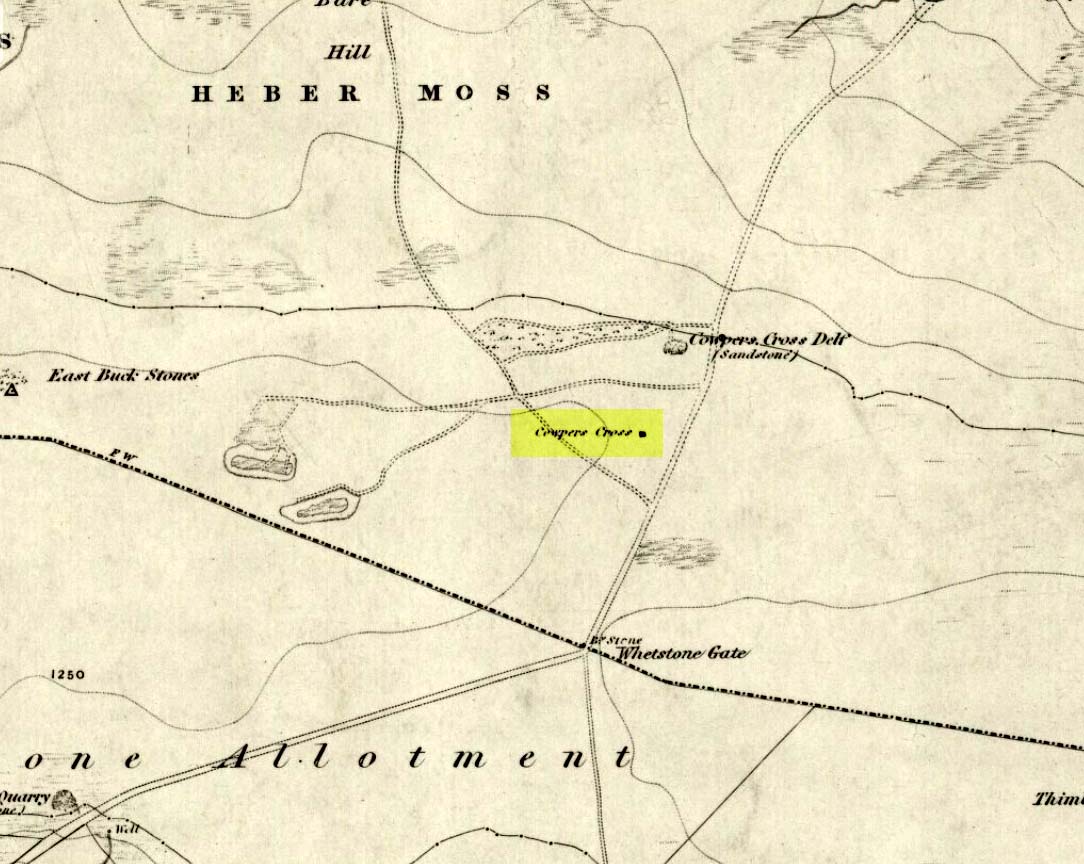

Ring Cairn: OS Grid Reference – SE 13648 44719

Also known as:

- Grubstones Circle

- Rumbles Law

- Rums Law

Get to the Twelve Apostles stone circle, then walk just 100 yards down the main footpath south, towards Bingley, and watch out for a small footpath immediately to your left. Walk on here and head for the rocky outcrop a half-mile ahead of you. Once past the outcrop, take the first footpath right and walk down for another 100 yards. Stop! – and walk into the heather. The circle’s about 50 yards away! You can of course come from the Menston side of the moor, following the same directions for the Great Skirtful of Stones, but keep walking on for another 200 yards, towards the rocky outcrop again, turning left down the path for 100 yards, before stopping and walking 50 yards into the heath again!

Archaeology & History

This is one of my favourite sites on these moors. I’m not 100% sure why – but there’s always been something a bit odd about the place. And I don’t quite know what I mean, exactly, when I say “odd.” There’s just something about it… But it’s probably just me. Though I assume that me sleeping rough here numerous times in the past might have summat to do with it, playing with the lizards, and of course…the sheep… AHEM!!! Soz about that – let’s just get back to what’s known about the place!

Grubstones is an intriguing place and, I recommend, recovers its original name of Roms or Rums Law. It was described as such in the earliest records and only seems to have acquired the title ‘Grubstones’ following the Ordnance Survey assessment in the 1850s. The name derives from two compound words, rum, ‘room, space, an open space, a clearing’; and hlaw, a ‘tumulus, or hill’ – literally meaning here the ‘clearing or place of the dead,’ or variations thereof. But an additional variant on the word law also needs consideration here, as it can also be used to mean a ‘moot or meeting place’; and considering that local folklore, aswell as local boundary records tell of this site being one of the gathering places, here is the distinct possibility of it possessing another meaning: literally, ‘a meeting place of the dead’, or variations on this theme.

The present title of Grubstones was a mistranslation of local dialect by the Ordnance Survey recorders, misconstruing the guttural speaking of Rum stones as ‘grub stones.’ If you wanna try it yourself, talk in old Yorkshire tone, then imagine some Oxford or London dood coming along and asking us the name of the ring of stones! It works – believe me….

The site has little visual appeal, almost always overgrown with heather, but its history is considerable for such a small and insignificant-looking site. First described in land records of 1273 CE, Roms Law was one of the sites listed in the local boundary perambulations records which was enacted each year on Rogation Day (movable feast day in Spring). However in 1733 there was a local boundary dispute which, despite the evidence of written history, proclaimed the Roms Law circle to be beyond the manor of Hawksworth, in which it had always resided. But the boundary was changed – and local people thenceforth made their way to the Great Skirtful of Stones on their annual ritual walk: a giant cairn several hundred yards east to which, archaeologically, there is some considerable relationship. For at the northern edge of the Roms Law circle is the denuded remnants of a prehistoric trackway in parts marked out with fallen standing stones and which leads to the very edge of the great cairn. This trackway or avenue, like that at Avebury (though not as big), consists of “male” and “female” stones and begins – as far as modern observations can tell – several hundred yards to the west, close to a peculiar morass of rocks and a seeming man-made embankment (which I can’t make head or tail of it!). From here it goes past Roms Law and continues east towards the Great Skirtful, until it veers slightly round the southern side of the huge old tomb, then keeps going eastwards again into the remnants of a prehistoric graveyard close by.

In my opinion, it is very likely that this trackway was an avenue along which our ancestors carried their dead. Equally probable, the Roms Law Circle was where the body of the deceased was rested, or a ritual of some form occurred, before taken on its way to wherever. It seems very probable that this avenue had a ceremonial aspect of some form attached to it. However, due to the lack of decent archaeological attention, this assertion is difficult to prove.

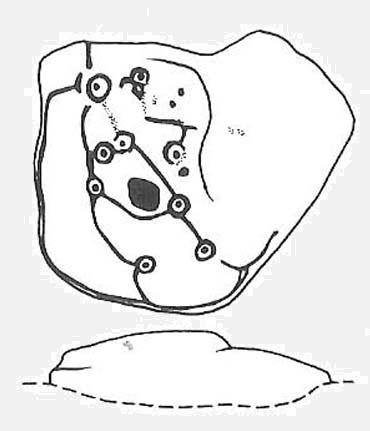

A previously unrecognised small single tomb is in evidence to the immediate southeast (5 yards) of the circle. There is also another previously unrecognised prehistoric trackway that runs up along the eastern side of the circle, roughly north-south, making its way here from Hawksworth Moor to the south. The old legend that Roms Law was a meeting place may relate to it being a site where the dead were rested, along with it being an important point along the old boundary line. Records tell us that the chant, “This is Rumbles Law” occurred here at the end of the perambulation – which, after the boundary change, was uttered at the Great Skirtful. This continued till at least 1901.

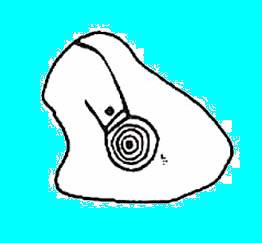

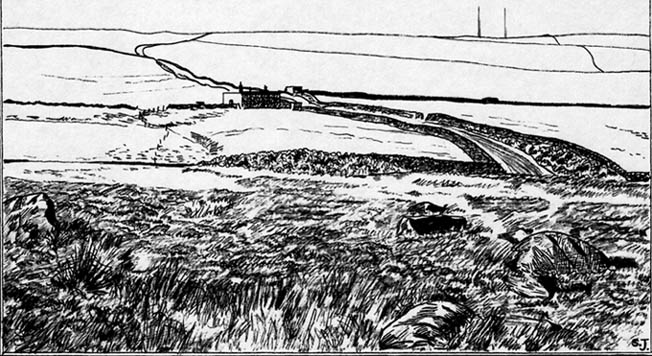

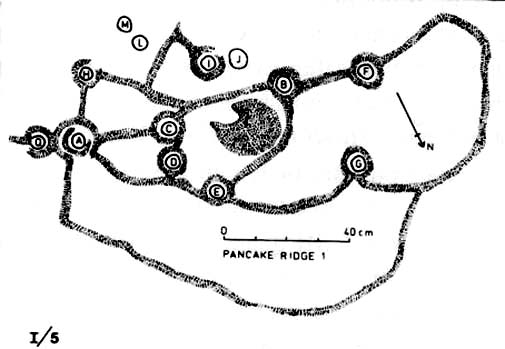

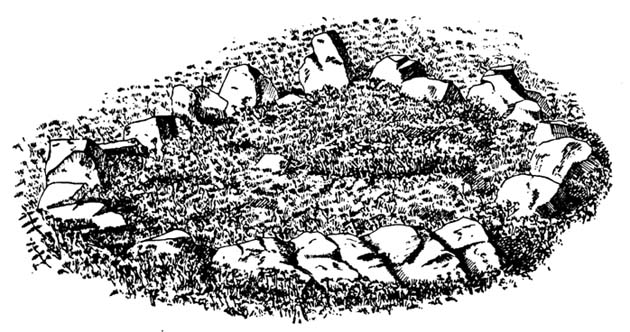

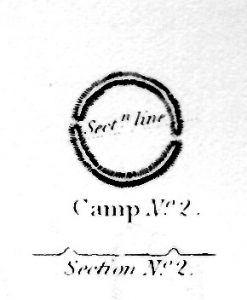

Modern archaeological analysis of the site is undecided as regards the actual nature of Roms Law. Ordnance Survey maps show it as an “enclosure” (which is vague); Faull & Moorhouse’s survey (1981) erroneously tell us it had no funerary nature, contrary to Eric Cowling’s (1946) report of finding bones and ashes from the small hole in near the centre of the ring, aswell as the 1880 drawing of the site in Collyer & Turner’s survey (above). And we find the single cairn on the south-eastern edge of the ring indicating burial rites of sorts definitely occurred here. Described variously by previous archaeologists as a stone circle, a ring cairn, cairn circle, an enclosure, aswell as “a rubble-fill wall of a circular house” (by some anonymous member of the West Yorkshire Archaeology Service, who didn’t respond to my queries about this curious assumption), the real nature of Roms Law leans more to a cairn circle site. A fine example of a cup-and-ring stone — the Comet Stone — was found very close to the circle, somewhere along the Grubstones Ridge more than a hundred years ago, and it may have had some relevance to Roms Law.

This denuded ring of stones is a place that has to be seen quite blatantly in a much wider context, with other outlying sites having considerable relationship to it. Simple as! (If you wanna know more about this, check out my short work, Roms Law, due out shortly!)

Describing the status and dimensions here, our great Yorkshire historian Arthur Raistrick (1929) told that:

“The larger stones still standing number about twenty, but the spaces between them are filled with stones of many intermediate sizes, so that one could with only considerable detail of size, etc, number the original peristalith.”

…Meaning that we’re unsure exactly how many stones stood in the ring when it was first built! Although a little wider, the Roms Law is similar in form to the newly discovered ‘Hazell Circle‘ not far from here. The site has changed little since Raistrick’s survey, though some halfwits nicked some of the stones on the southwestern edge of the site in the 1960s to build a stupid effing grouse-butt, from which to shoot the birds up here! (would the local council or local archaeologist have been consulted about such destruction by building the grouse-butt here? – anyone know?) Thankfully, this has all but disappeared and the moorland has taken it back to Earth.

There is still a lot more to be told of Roms Law and its relationship with a number of uncatalogued sites scattered hereby. Although it’s only a small scruffy-looking thing (a bit like misself!), its archaeology and mythic history is very rich indeed. “Watch This Space” – as they say!

Folklore

Alleged to be haunted, this site has been used by authentic ritual magickians in bygone years. It was described by Collyer & Turner (1885) “to have been a Council or Moot Assembly place” — and we find this confirmed to a great extent via the township perambulation records. Considerable evidence points to an early masonic group convening here in medieval times and we are certain from historical records that members of the legendary Grand Lodge of All England (said to be ordained in the tenth century by King Athelstan) met here, or at the adjacent Great Skirtful of Stones giant cairn 400 yards east.

The boundary perambulations which occurred here on Rogation Day relate to events just before or around Beltane, Mayday. Elizabeth Wright (1913) said of this date:

“These days are marked in the popular mind by the ancient and well-known custom of beating the parish bounds, whence arose the now obsolete name of Gang-days, and the name Rammalation-day, i.e., perambulation-day, for Rogation-Monday. The practice is also called Processioning and Possessioning… The reason why this perambulation of the parish boundaries takes place at Rogationtide seems to be that originally it was a purely religious observance, a procession of priest and people through the fields to pray for a fruitful Spring-time and harvest. In the course of time the secular object of familiarizing the growing generation with their parish landmarks gained the upper hand, but the date remained as testimony to the primary devotional character of the custom.”

And the calling of, “This is Rumbles Law” maintained this ancient custom when it used to be uttered here.

…to be continued…

References:

- Bennett, Paul, The Old Stones of Elmet, Capall Bann: Milverton 2001.

- Bennett, Paul, The Roms Law Circle, Ilkley Moor, Heathen Earth: Keighley 2009.

- Bennett, Paul, The Twelve Apostles Stone Circle, TNA Publications 2017.

- Collyer, Robert & Turner, J. Horsfall, Ilkley: Ancient and Modern, William Walker: Otley 1885.

- Colls, J.N.M., ‘Letter upon some Early Remains Discovered in Yorkshire,’ in Archaeologia 31, 1846.

- Cowling, E.T., Rombald’s Way, William Walker: Otley 1946.

- Devereux, Paul, Places of Power, Blandford: London 1989.

- Faull & Moorhouse, West Yorkshire: An Archaeological Survey – volume 1, WYMCC: Wakefield 1981.

- Gelling, Margaret, Signposts to the Past, Phillimore: Chichester 1988.

- Gelling, Margaret, Place-Names in the Landscape, Phoenix: London 2000.

- Gomme, G.L., Primitive Folk-Moots; or Open-Air Assemblies in Britain, Sampson Low: London 1880.

- Raistrick, Arthur, ‘The Bronze Age in West Yorkshire,’ in YAJ, 1929.

- Smith, A.H., English Place-Names Elements – volume 2, Cambridge University Press 1956.

- Smith, A.H., The Place-Names of the West Riding of Yorkshire – volume 4, Cambridge University Press 1963.

- Speight, Harry, Chronicles and Stories of Old Bingley, Elliott Stock: London 1898.

- Wardell, James, Historical Notices on Ilkley, Rombald’s Moor, Baildon Common, etc., Leeds 1869.

- Wright, Elizabeth Mary, Rustic Speech and Folk-Lore, Oxford University Press 1913.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.