Cursus: OS Grid Reference – NZ 234 010 to SE 249 996

Archaeology & History

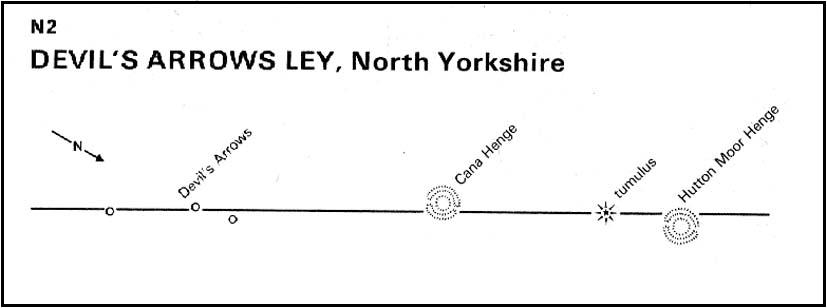

A huge linear monument that could once be found on the flats just north of the B6271 road running between the villages of Scorton and Brompton-on-Swale, east of the ancient A1 road, has long since been ruined. Although found quite a few miles north of the main Thornborough henge and cursus complex, a number of students still posit that this northern monument was part of the same “ritual landscape” arena.

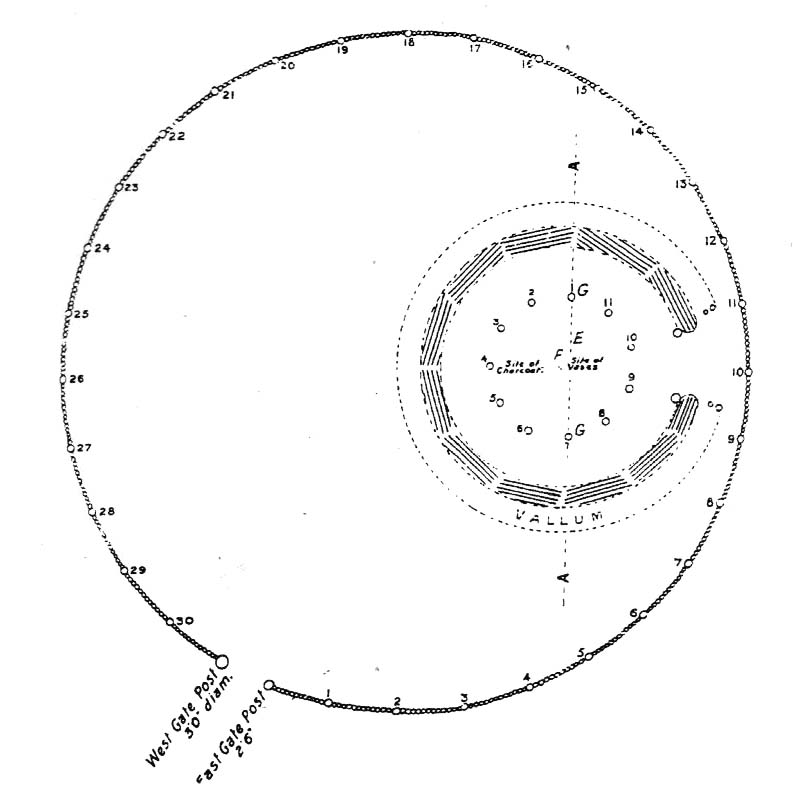

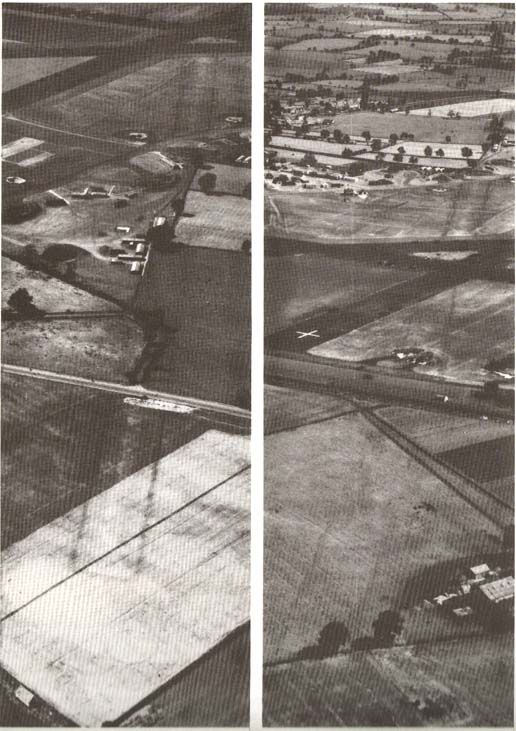

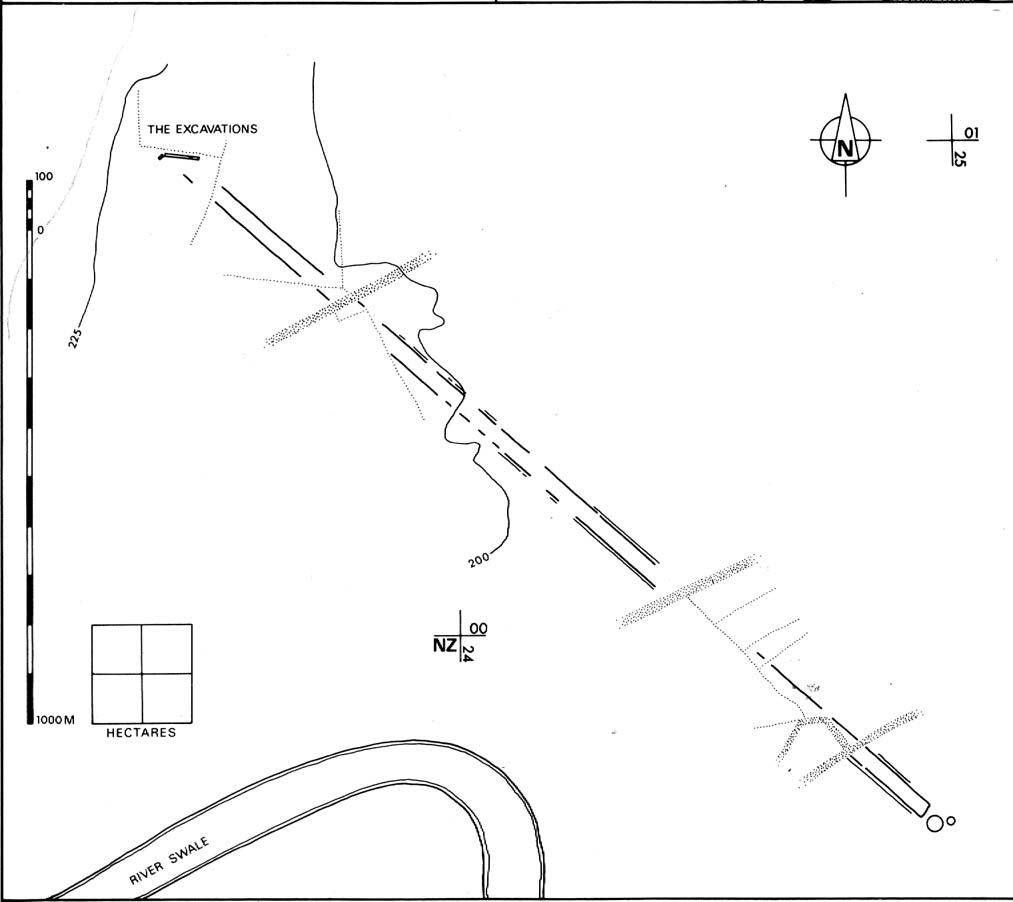

First discovered in 1949 following aerial survey analysis by Prof. J.K. St. Joseph, this huge dead straight cursus monument ran for at least 1.3 miles (2.1km) and would have been considerably longer if the self-righteous advance of industry hadn’t quarried it away (such is “progress”!). Built along a southeast to northwest axis, the southern end of the cursus was straight and flattened (as opposed to convex, as found at some cursuses), as Peter Topping’s (1982) illustration of the monument here shows, but the northwestern end of the cursus has not been found. As Mr Topping himself wrote:

“The southwestern terminal, which shows clearly on the aerial photographs, consists of a straight transverse ditch which joins the two main ditches at right angles. Clustering around it was a series of ring-ditch cropmarks. The aerial photographs also show a series of bleach marks between the ditches at the southern end of the cursus, which may represent a series of contiguous mounds. This area of the cursus also features what appears to be smaller outer ditches…”

Topping also commented on a most “noteworthy feature” in the accuracy of the ditches that constitute the length of the monument, being so “remarkably straight considering the distance over which they extend.” Features which, in bygone days, a number of respected archaeologists denied our prehistoric ancestors the ability to execute.

Hopefully readers will forgive me citing more of Topping’s extensive notes regarding the archaeological analysis of this site, but I think they’re worthwhile. Of the ditches that make up the outline of the cursus, he told:

“The ditches of the cursus are the two most prominent features of this site on the aerial photographs. …The only evidence available for the existence of the cursus in the area to be excavated was a section exposed in the adjacent gravel quarry. This section clearly illustrated quite distinct re-cut features visible in the profiles of both ditches, and evidence of this recutting was also discovered in the excavated areas. However, one anomaly which did distinguish the excavated sections from those exposed in the quarry was the variable depth of the ditches. In the quarry-face sections the western ditch had a maximum depth of 60cms, while in the excavated area its maximum depth was 45cm; similarly, the eastern ditch had a maximum depth of 65cm in the quarry and a maximum depth of 43 cm in the excavations. This may have resulted from the actions of hillwash or ploughing reducing the height of the old land surface in this area where the ground naturally rises, or alternatively indicate no more than an uneven depth to the ditches. Their width was fairly consistent, the maximum width of the eastern ditch being 3.40m, while that of the western ditch was 3.85m.

“Recutting in both ditches was indicated by a V-shaped notch beneath the main profile of the ditch…

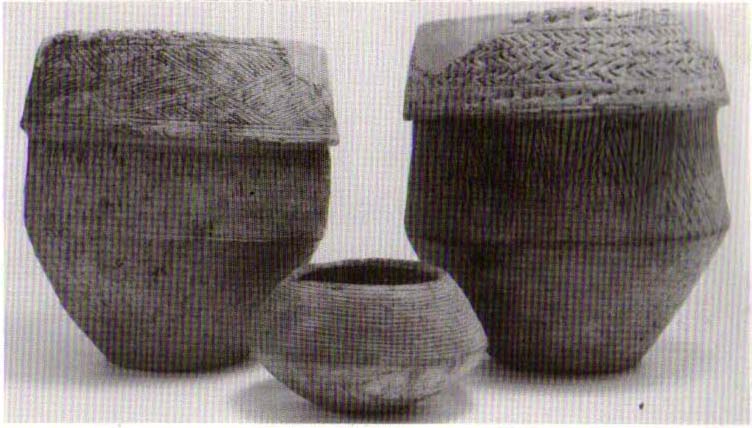

“Closely datable artifacts were sadly lacking in the ditches, the one possible exception being (a) flint…possibly an arrowhead, from the upper fill of the eastern ditch… The upper fill of the eastern ditch also produced (a) flint…”

But in all honesty, these flint finds were probably of little importance to the cursus itself and can be discounted as of any relevance outside of being stray hunting flints. Three other flints were discovered by the western ditch aswell, again with little significance to the monument. But the next part of the excavation work explored what Topping called the ‘Central Feature’, of which he said:

“Bleach marks on Prof. St. Joseph’s aerial photographs revealed what appeared to be a series of axially-placed contiguous mounds situated between the main ditches, and extending the whole length of the long axis of the monument as then known. The presence of this feature was confirmed in the excavated area. A low central mound was uncovered, within and respecting the lines of the ditches, which had a maximum height of 32cm above the old ground surface.”

Upon further excavation they found what one would have expected: little more than the upcast of earth and gravel dug out from the ditch that makes up the cursus, i.e., spoil-heaps made where they’d dug out the cursus lines with little other significance. This feature is obviously apparent in many cursuses. Of greater interest was the pit- or post-hole on the eastern ditch.

“This was stratigraphically related to the cursus to the extent that it was sealed by the same layer of hill-wash that had buried the cursus ditches. In addition, this feature clearly respected the limits of the eastern ditch. The dimensions of the pit/post-hole were: maximum diameter at its base, 1.12m, the maximum width at its top, 2.10m, length, 4.19m, and a maximum depth of 60cm.

“…Distinct tip-lines were evident leading in and downwards towards the centre of the feature, this central area being relatively stone-free. This could suggest that the feature originally held a post which was subsequently removed at a later date.”

I’d say this notion is highly likely! In the event that a complete excavation could have been made here, it’s probable they would have found other pit-holes into which upright wooden posts were erected around the time the cursus was constructed. When Topping and his team excavated sections of the eastern ditch-floor, they found what appeared to be the truncated base of another post-hole. He told:

“This feature was sectioned and found to be flat-bottomed and to have a depth of only 3cm and a diameter of 25cm. The fill was indistinguishable from the fill of the cursus ditch and contained no traces of organic material…although the exact function of this feature is unknown.”

Topping’s conclusion about the nature and function of this monument is a simple one:

“it can be seen as part of a concentration or complex of magico-religious structures.”

And although this is a somewhat tentative notion based on the limited archaeological evidence here, it does accord with standard views in comparative religion on the animistic relation humans had with natural and man-made monuments from this and later periods of history; as well as reflecting the findings on the origin and development of human consciousness in Jungian and other applied psychology schools. The construction of this gigantic landscape feature occurred at a period in human history when the division between the sacred and the profane had yet to emerge culturally. In all likelihood, Mr Topping’s notion is correct.

References:

- Moorhouse, S., ‘The Yorkshire Archaeological Register: 1975,’ in Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, 51, 1979.

- Pennick, Nigel & Devereux, Paul, Lines on the Landscape, Hale: London 1989.

- Thorp, F., ‘The Yorkshire Archaeological Register: 1975,’ in Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, 48, 1976.

- Topping, Peter, ‘Excavation at the Cursus at Scorton, North Yorkshire, 1978,’ in Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, 54, 1982.

Acknowledgements:

To the Yorkshire Archaeological Society for use of Peter Topping’s drawing & to Cambridge University for use the aerial photograph.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.