Legendary Stone & Healing Well (lost): OS Grid Reference – NN 579 323

Also Known as:

- Fuaran na Druidh Chasad

- Whooping Cough Well

Archaeology & History

The grid-reference given for this site is only an approximation based on the description given by Hugh MacMillan (1884), below. The exact whereabouts of the place remains forgotten, but based on the story we have of the place it would be great if we could locate it and — as far as I’m concerned — be highlighted and preserved as an important spot in the history of religious and social history for the people of Killin and the wider mountain community. The region here was well populated all along the northern and southern sides of the adjacent Loch Tay before the coming of the Highland Clearances (Prebble 1963), and so the lore which MacMillan describes below was very likely of truly ancient pedigree.

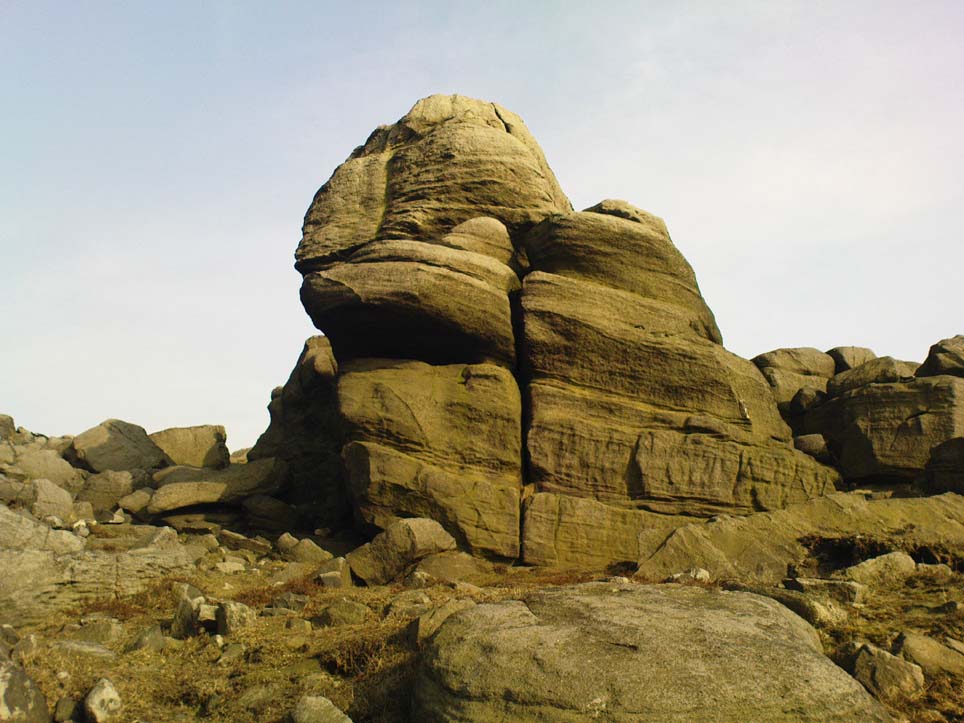

Not to be confused with a site of the same name (and attributes) as the healing well at Balquhidder, this site comprises of a large stone, typical of the region, covered in that delicious carpet of old mosses and lichen bestowed by the aged love from Nature that bedecks much of the hidden sites in the area. Upon one side of the rock was a large hollow, in which water was always collected: of both dew and rain and the breath of low clouds, within which were great medicinal virtues long known of by local people. Foreign or shallow archaeologists would denounce this rock and its virtues as little more than the superstitious beliefs of an uneducated people living in uneducated times, but such derision is simply foolish words from pretentious souls who know little of the real world. For the attributes and mythic elements at this old stone is another example of living animism: vitally important ingredients in the spiritual background and nourishment of a people not yet overcome by the degrading influence of homo-profanus. Here we still find the living principles of the natural world, sleeping away in the consensus trance of modern folk…

Folklore

The stone and its ‘healing well’ are not mentioned in the standard Scottish texts on holy wells (MacKinlay 1893; Morris 1982) and we have to rely solely on Hugh MacMillan’s first-person account of the place from the latter-half of the 19th century. He told that the stone was to be found “in the woods of Auchmore at Killin,” some twelve miles from a similar curative rock at Fearnan called the Clach-na Cruich:

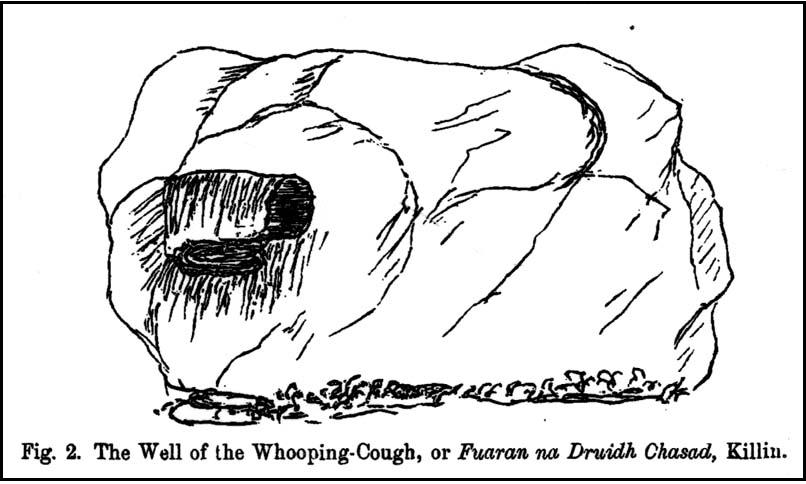

“This stone is called Fuaran na Druidh Chasad, or the Well of the Whooping-Cough. I heard of it incidentally last year in Paisley from a native of Killin, who remembered vividly when a boy having been taken to drink the water in the cavity of the stone, in order to cure the whooping-cough, from which he was suffering at the time. Happening to be in Killin lately, enjoying a few days’ holiday, I made inquiries in the village; but though some of the older inhabitants remembered having heard of the stone, and the remarkable practice connected with it, I could not get any one to describe the exact locality of it to me, so completely has the superstition passed away from the mind of the present generation. I went twice in search of the stone; and though, as I afterwards found, I had been within a very short distance of it unawares on both occasions, I was unsuccessful in finding it. At last I met an old man, and after some search we found the stone, and he identified it.

“I understood then what had puzzled me before, viz., why it should have been called Fuaran or Well, for I had supposed it had a cavity in a stone like that at Fernan. It was indeed a cavity; but it was in the projecting side of the stone, not on its top surface. It consisted of a deep basin penetrating through a dark cave-like arched recess into the heart of the stone. It was difficult to tell whether it was natural or artificial, for it might well have been either, and was possibly’ both; the original cavity having been a mere freak of nature — a weather-worn hole — afterwards perhaps enlarged by some superstitious hand, and adapted to the purpose for which it was used. Its sides were covered with green cushions of moss; and the quantity of water in the cavity was very considerable, amounting probably to three gallons or more. Indeed, so natural did it look, so like a fountain, that my guide asserted that it was a well formed by the water of on underground spring bubbling up through the rock. I said to him, “Then why does it not flow over?” That circumstance he seemed to regard as a part of its miraculous character to be taken on trust. I put my hand into it, and felt all round the cavity where the water lay, and found, as was self-evident, that its source of supply was from above and not from below; that the basin was simply filled with rain water, which was prevented from being evaporated by the depth of the cavity, and the fact that a large part of it was within the arched recess in the stone, where the sun could not get access to it. I was told that it was never known to be dry — a circumstance which I could well believe from its peculiar construction.

“The stone, which was a rough irregular boulder, somewhat square-shaped, of mica schist, with veins of quartz running through it, about 8 feet long and 5 feet high, was covered almost completely with luxuriant moss and lichen; and my time being limited, I did not examine it particularly for traces of cup-marks. There were several other stones of nearly the same size in the vicinity, but there was no evidence, so far as I could see, of any sepulchral or religious structure in the place. There is indeed a small, though well-formed and compact so-called Druidical circle, consisting of some seven or eight tall massive stones, with a few faint cup-marks on one of them, all standing upright within a short distance on the meadow near Kinnell House, the ancestral seat of the Macnabs, and it is a reasonable supposition that the Fountain of the Whooping-Cough may have had some connection in ancient times with this prehistoric structure in its immediate neighbourhood; for, unlike the cavity in the stone at Fernan, the peculiar shape of the cavity in this stone precluded its ever having been used as a mortar, and apparently it has never been used for any other purpose than that which it has so long served. There can be no doubt that the fountain dates from a remote antiquity; and the superstition connected with it has survived in the locality for many ages. It has now passed away completely, and the old stone is utterly neglected. The path leading to it, which. used to be constantly frequented, is now almost obliterated. This has come about within the last thirty years, and one of the principal causes of its being forgotten is that its site is now part of the private policies of Auchmore. The landlady of the house at Killin, where I resided, remembered distinctly having been brought to the stone to be cured of the whooping-cough; and, at the foot of it, there are still two flat stones that were used as steps to enable children to reach up to the level of the fountain, so as to drink its healing waters; but they are now almost hidden by the rank growth of grass and moss. There is more verisimilitude about the supposititious cures effected at this fountain than about those connected with the stone at Fernan; for one of the best remedies for the whooping-cough, it is well known, is change of air, and this the little patient would undoubtedly get, who was brought, it may be, a considerable distance to this spot. I am led to understand that, in connection with the cure, the ceremonial turn called “Deseul” was performed. The patient was required, before drinking the water, to go round the stone three times in a right-hand direction, which may be regarded as an act of solar adoration. This practice lingered long in this as in other parts of the Highlands, and the “deseul” was religiously performed round homesteads, newly-married couples, infants before baptism, patients to be cured, and persons to whom good success in some enterprise was wished; while the “Tuathseul,” or the unhallowed turn to the left, was also performed in cases of the imprecation of evil.”

Should anyone know the whereabouts of this fascinating healing stone and its waters, please let us know!

References:

- MacKinlay, James M., Folklore of Scottish Lochs and Springs, William Hodge: Glasgow 1893.

- MacMillan, Hugh, ‘Notice of Two Boulders having Rain-Filled Cavities on the Shores of Loch Tay, Formerly Associated with the Cure of Disease,’ in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 18, 1884.

- Morris, Ruth & Frank, Scottish Healing Wells, Alethea: Sandy 1982.

- Prebble, John, The Highland Clearances, Secker & Warburg: London 1963.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.