Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – NN 79746 47251

Follow the same directions for the Croft Moraig stone Circle. Then check out the elongated stone lying in the grass on the southern edge of the circle. It’s not that hard to find!

Archaeology & History

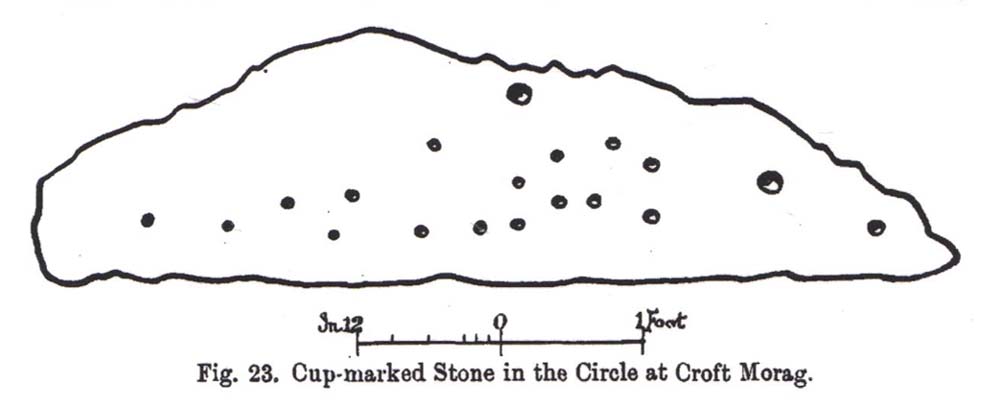

Nearly 13 yards (11.75m) south of the faded Croft Moraig 2 carving, this cup-and-ring stone on the SSW edge of Croft Moraig is one of at least four that have been found in this megalithic ring. It has been suggested that the stone on which the carving is found once stood upright. The earliest account I’ve found of it comes from Alex Hutcheson’s (1889) essay in which he wrote:

“At the south-west side and in the line of the outer circle lies the cupmarked stone. It is a recumbent stone, and like the others in that circle lies with its larger axis in the direction of the encircling line. It measures 6 feet 6 inches long by 2 feet broad, and bears on its surface 23 cups. Two of these are connected by straight channels. The largest cup is 2 inches in ‘diameter and f inch deep. Two of the cups are encircled, each with a concentric ring. None of the other stones exhibit any cups or other artificial markings.”

…Although other cup-marks have subsequently been found on other stones within the circle. Consistent with the location of cup-and-ring marks elsewhere in the country, Hutcheson found the carved rock to be just in front of “a longish low mound of small stones, like an elongated cairn, which might yield something if it were to be searched.” Very little of this cairn remains today.

When Fred Coles (1910) came to explore Croft Moraig about 20 years later, he could only discern 19 cups on the stone, most of them the same size, “only two of which differ much in diameter and depth from the rest.” The cup-and-ring that Hutcheson described and the other missing cups had been overgrown by the grasses, Coles said. When Sonia Yellowlees described the carving in 2004, she said that 21 cups were visible, “one of which is surrounded by a single ring”—which you can clearly see in the photos below.

When archaeologist Evan Hadingham (1974) looked at this site, he found deposits of quartz here and thought that their presence may have been relevant to the placement of the carving, noting how such a relationship is found at other circles in Scotland. In more recent years, rock art students Richard Bradley and others have found similar quartz deposits in or around some petroglyphs a few miles from here; as have fellow students Jones, Freedman and o’ Connor (2011) at some of the rock art around Kilmartin. In my own explorations of the carvings near Stag Cottage, hundreds of quartz chippings were found that had been pecked into the cups and rings.

References:

- Burl, Aubrey, Rings of Stone, Frances Lincoln: London 1979.

- Coles, Fred, “Report on Stone Circles Surveyed in Perthshire,” in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 44, 1910.

- Hadingham Evan, Ancient Carvings in Britain: A Mystery, Garnstone: London 1974.

- Hutcheson, Alexander, “Notes on the Stone Circle near Kenmore,” in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 23, 1889.

- Piggott, Stuart & Simpson, D., “Excavation of a Stone Circle at Croft Moraig, Perthshire,” in Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, volume 37, 1971.

- Yellowlees, Walter, Cupmarked Stones in Strathtay, Scotland Magazine: Edinburgh 2004.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.