Holy Well (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – SE 308 336

Archaeology & History

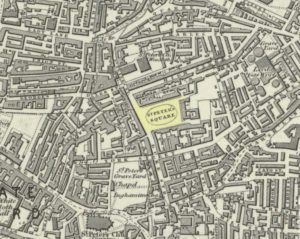

This is one of three wells that were dedicated to St Peter in the Leeds district. The first of them, near the city centre, was described by the northern antiquarian Ralph Thoresby (1715) as being in St. Peter’s Square—which has now been completely built over, but was situated “at the bottom or west end of High Street,” (Bonser 1974) about 50 yards west of the modern Quarry Hill buildings. It was well known in the area in early times with a good curative reputation due seemingly to its sulphur content. Mr Thoresby told that us, it

“is intensely cold and very beneficial for such as are afflicted with rheumatic pains, or weakness, rickets, etc, for which reason it is much frequented by such, who might otherwise have recourse to St. Mungus or Mongah, as it is more truly writ. This Spring, according to St Anselms Canon, which forbad a credulous attributing any reverence, or opinion of holiness to fountains…must either have been of great antiquity, or have had the bishop’s authority.”

Local folk of course, would have long known the goodness of this water supply long before any crude bishop. The well either possessed a very large stone trough or it had been fashioned and added to by locals, as Thoresby reported “trying the cold bathing of St Peter’s.” He took his youngest child there, Richard, to help him overcome an osteopathic ailment. In his diary entry for April 8, 1709, he wrote:

“Was late at church, and fetched out by a messuage from the bone-setter (Smith, of Ardsley), who positively affirms that one part of the kneebone of my dear child Richard, has slipped out of its proper place; he set it right and bound it up; the Lord give a blessing to all endeavours! We had made use of several before, who all affirmed that no bone was wrong, but that his limp proceeded rather from some weakness, which we were the rather induced to believe, because warm weather, and bathing in St. Peter’s Well, had set him perfectly on his feet without the least halting, only this severe Winter has made him worse than ever.”

It later became at least one of the water supplies for Maude’s Spa close by. As usual with health-giving waters at this period in the evolving cities, money was to be made from them and local folk had to find their supplies from other sources. St Peter’s Sulphur Baths (as it was called) were built on top of it in the 19th century and, said Bonser “flourished until the early years of the (20th) century.”

Although I can find no notices of annual celebrations or folklore here, St. Peter’s Day is June 29 — perhaps a late summer solstice site, though perhaps not.

It would be good if Leeds city council would at least put historical plaques in and around the city to inform people of the location of the many healing and holy wells that were once an integral part of the regions early history. Tourists of various interest groups (from christian to pagan and beyond) would love to know more about their old sacred sites and spend their money in the city.

References:

- Atkinson, D.H., Ralph Thoresby, the Topographer – volume 1, Walker & Laycock: Leeds 1885.

- Baines, Edward, The Leeds Guide, E.Baines: Leeds 1806.

- Bonser, K.J., “Spas, Wells and Springs of Leeds,” in Publications Thoresby Society, 54:1, 1974.

- Harte, Jeremy, English Holy Wells – volume 2, Heart of Albion: Wymeswold 2008.

- NiBride, Feorag, The Wells and Springs of Leeds, Pagan Pratlle: Leeds 1994.

- Robinson, Percy, Relics of Old Leeds, P.Robinson: Leeds 1896.

- Smith, Andrea, ‘Holy Wells Around Leeds, Bradford & Pontefract,’ in Wakefield Historical Journal 9, 1982.

- Thoresby, Ralph, Ducatus Leodiensis, Maurice Atkins: London 1715.

- Whelan, Edna & Taylor, Ian, Yorkshire Holy Wells and Sacred Springs, Northern Lights 1989.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.