Cup-and-Ring Stone (lost): OS Grid Reference – SE 1015 4702

Also Known as:

- Panorama Rock 226

Archaeology & History

It would seem that this excellent looking cup-and-ring stone may have been destroyed sometime around 1890 during the construction of the Panorama Reservoir and the building of the houses on the southwestern edge of Ilkley, right by the moorside. But this isn’t known for certain; and the carving could still exist beneath vegetation in the trees just north of the reservoir. In requesting to explore some National Archives data in which there may be information relating to this carving (and others nearby), I was directed to Bradford Council’s community archaeologist, Gavin Edwards (to whom requests should be made), but he denied access to look at the files, then completely ignored subsequent queries that might enable us to locate this and other important prehistoric carvings. So we did our best and this is what we’ve found so far (forgive any errors).

As there’s a slight ambiguity in the precise location of this lost carving, we cannot say for certain whether or not this site was included in the sale of Property Lots, numbers 7-34, “surrounding the far-famed Panorama Rocks,” which may have led to the site’s destruction and subsequent removal of the protected Panorama Stones to Saint Margaret’s Park on the other side of the road from the church, closer to Ilkley centre. The sale of this “building land” as it was called was advertised in the Leeds Mercury, Saturday September 4, 1880, with a brief description of the respective “lots” near this and the adjacent carvings. But this Panorama Stone 226 may have been left alone and be buried under the surface…

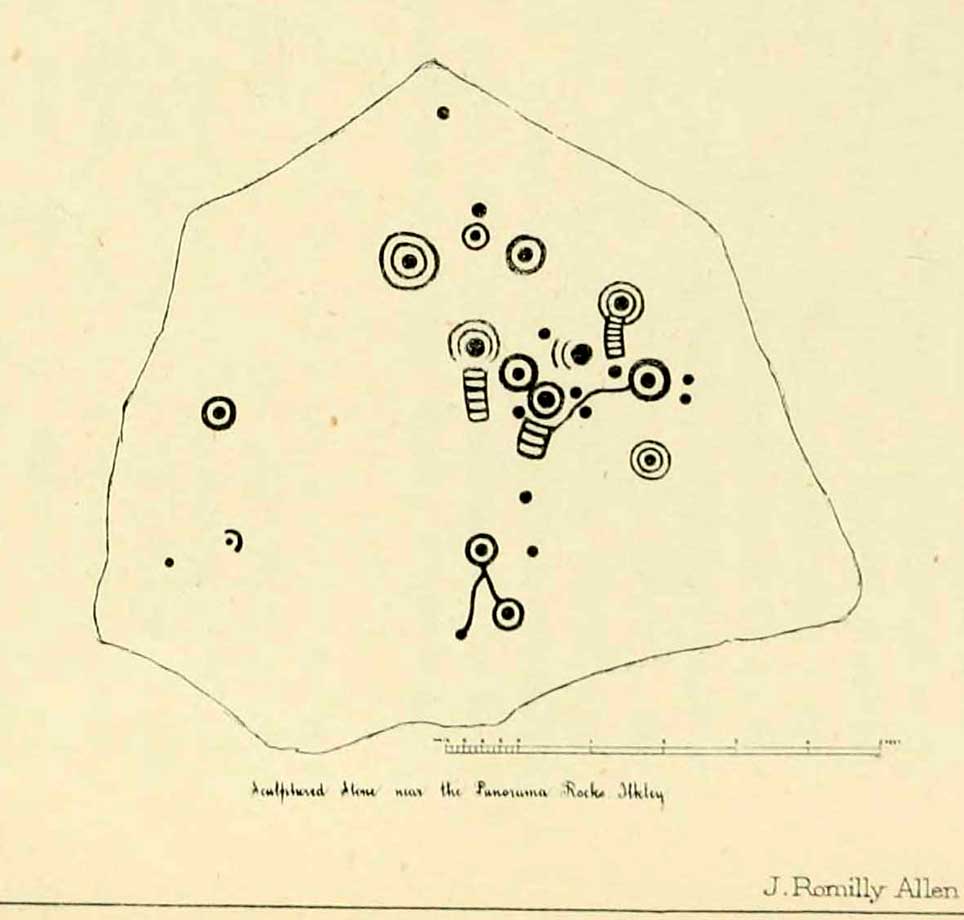

Historical notes on this particular stone are scattered and sparse, but digging through old journals and texts has given us a reasonably good vision of the place. It was first described, albeit in passing, in A.W. Morant’s edited third edition of Whitaker’s History of Craven (1878: 289), where it was described in context with the other cup-and-ring east of here on the same ridge. All of them were described as being located within a now-destroyed prehistoric enclosure (precise nature unknown), with carving 226 at the westernmost end. However, the following year J. Romilly Allen (1879) gave more details of this, “the third stone” as he called it and furnished us with a damn good drawing to boot!

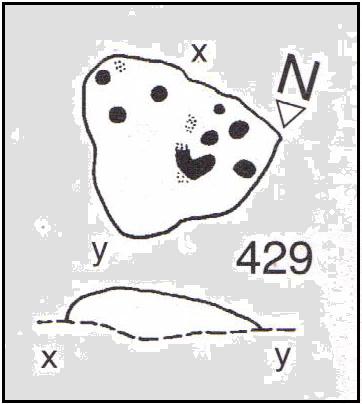

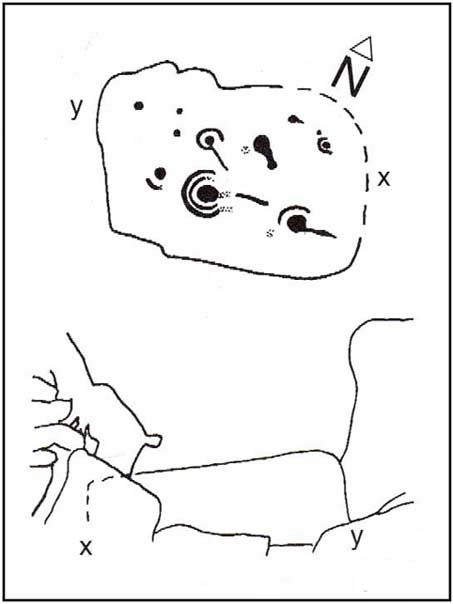

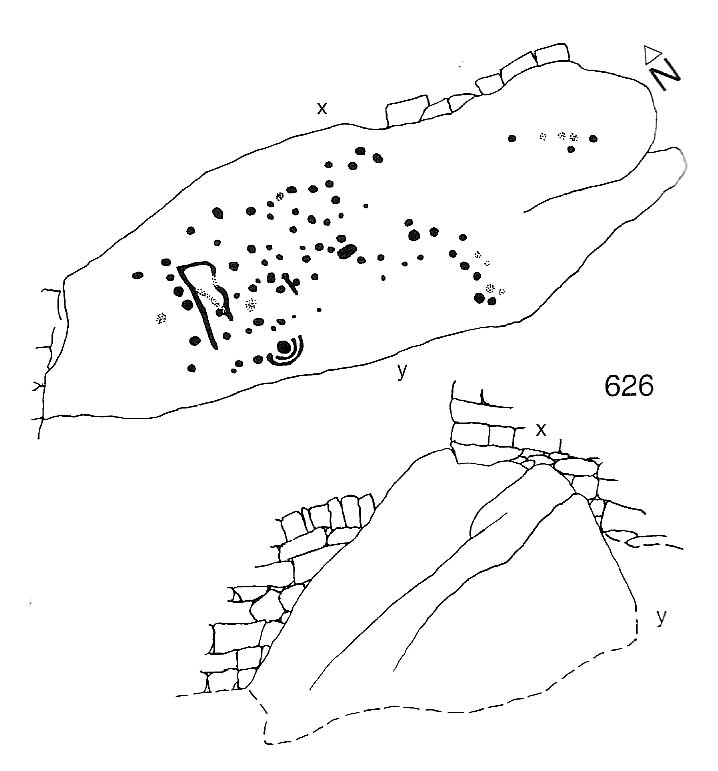

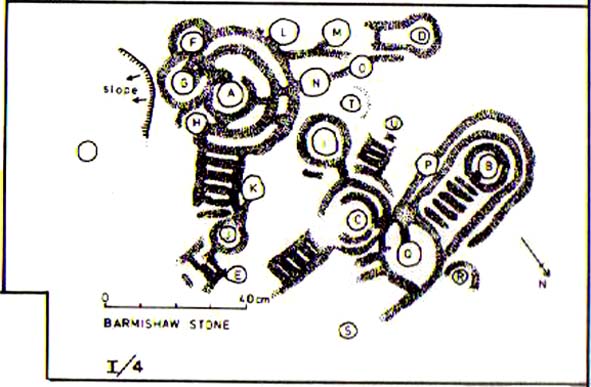

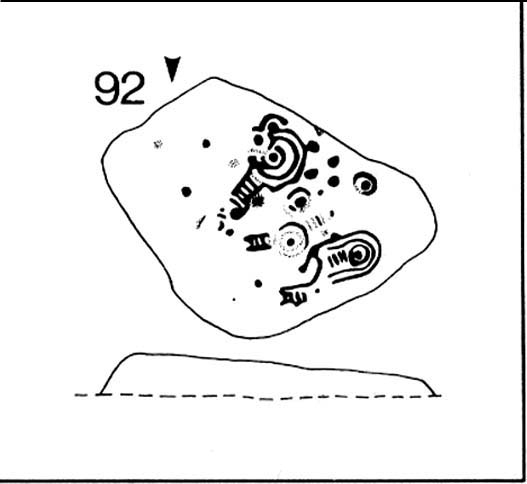

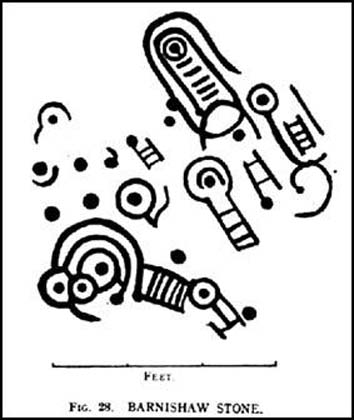

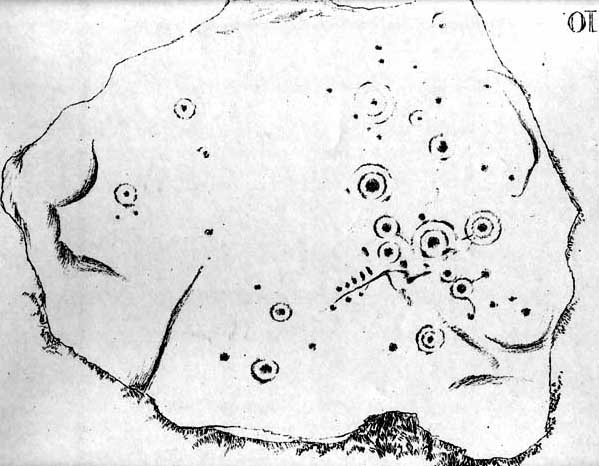

As we can see, there are four double-ringed cups and eight or nine archetypal cup-and-rings, with the usual scatter of cups falling across the design. The curious ‘ladder’ markings found on one of the other Panorama Stones, the Barmishaw Stone, Willy Hall’s Wood carving and at least one of the Baildon Moor carvings, were also quite prominent. Although when J. Thornton Dale visited here around the same time and did his own drawings, the ladders weren’t quite as pronounced. This would have been due to the simple factors of cloud cover, poorer sunlight and the time of day the drawings were done (the pseudoscientific proclamation of local archaeologist Gavin Edwards that such artistic difference is due to some Victorian chap adding, or removing sections of the carvings for his own pleasure, negates common sense and is strongly lacking in evidence). Romilly Allen’s own description of the site was as follows:

“The Panorama Rock lies one mile south-west of Ilkley, and from a height of 800 feet… About 100 yards to the west of this spot appears to be some kind of rough inclosure, formed of low walls of loose stones, and within it are the three finest sculptured stones near Ilkley. They lie almost in a straight line East to West… The third and most westerly stone of the group measures 10ft. by 9ft. and lies almost horizontally, having its face slightly inclined. On it are carved twenty-seven cups, fourteen of which have concentric rings round them. Some of the cups have connecting grooves, and three have the ladder-shaped pattern before referred to.”

Notes from a few years later told that this carving was still in situ when the companion carvings were moved and imprisoned behind railings across from St. Margaret’s Church in Ilkley. The carving was shown at the grid reference given above on the 1895 Ordnance Survey map of the region before the reservoir was built, correcting the coordinates given in Boughey & Vickerman’s (2003) otherwise fine survey. They described this very ornate carving thus:

“According to Thornton Dale (1880), this was a large rock with 27 cup, eighteen of which had single rings. Some of the cups had connecting grooves and three had the same ladder motif as the Panorama Stone.”

…to be continued…

References:

- Allen, J. Romilly, “The Prehistoric Rock Sculptures of Ilkley,” in Journal of the British Archaeological Association, volume 35, 1879.

- Allen, J. Romilly, “Notice of Sculptured Rocks near Ilkley,” in Journal of the British Archaeological Association, volume 38, 1882.

- Allen, J. Romilly, “Cup and Ring Sculptures on Ilkley Moor,” in The Reliquary, volume 2, 1896.

- Bennett, Paul, The Panorama Stones, Ilkley, TNA: Yorkshire 2012.

- Boughey, Keith, “The Panorama Stones,” in Prehistory Research Section Bulletin, no.40, Yorkshire Archaeological Society: Leeds 2003.

- Boughey, K.J.S. & Vickerman, E.A., Prehistoric Rock Art of the West Riding, WYAS: Leeds 2003.

- Collyer, Robert & Turner, J.H., Ilkley: Ancient and Modern, William Walker: Otley 1885.

- Jennings, Hargrove, Archaic Rock Inscriptions, A.Reader: London 1891.

- Turner, J. Horsfall, “British or Prehistoric Remains,” in Collyer & Turner, Otley 1885.

- Whitaker, Thomas Dunham, The History and Antiquities of the Deanery of Craven in the County of York, (3rd edition) Joseph Dodgson: Leeds 1878.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.