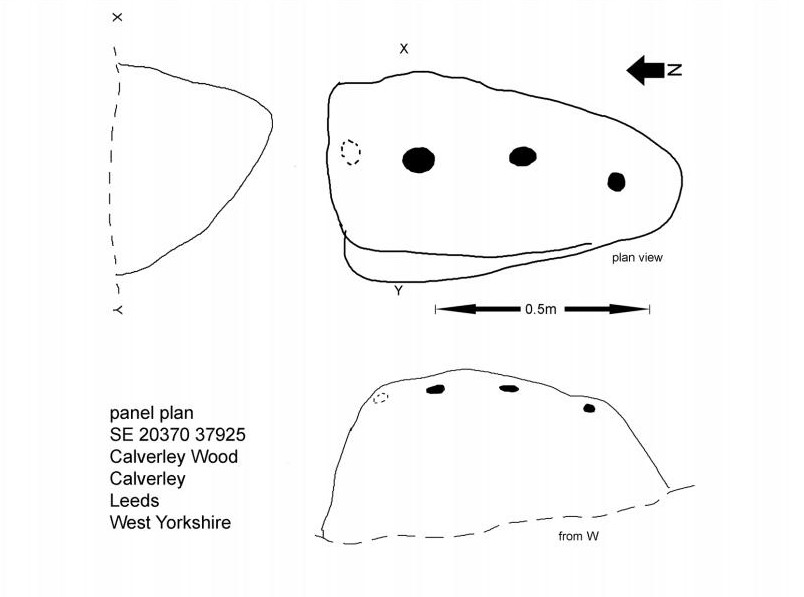

Cup-Marked Stone: OS Grid Reference – SE 20370 37925

(courtesy Mike Short)

Mike Short tells: Walk ENE along Thornhill Drive (no vehicular access) to gate across road at the last house on the Drive and continue on for approx 475m where road starts to narrow slightly, becomes a little steeper and gently turns to E. Thornhill Drive is now cut into the hillside at this point with an upwards sloping bank on the S side of the path. After approx 25m further on at approx SE 20375 37950 look out on the S side of the path for a pile of boulders sitting on bedrock on top of the bank and a large rectangular tabular rock on the side of the bank. Ascend the bank and from the boulder pile the panel is approx 22m 200º(T) in the middle of an ephemeral E-W path more defined to W.

Archaeology & History

The profile (and ‘How to Get There’) for this recently discovered cup-marked stone was forwarded to me by fellow rock art explorer, Mike Short. The carving is another basic design found in Calverley Woods, between Leeds and Bradford, nearly halfway between the missing petroglyphs of West Woods 2 and Sidney Jackson’s Calverley Woods Stone. Rediscovered by Lisa Volichenko some time ago, Mike described the new carving here as follows:

(courtesy Mike Short)

(courtesy Mike Short)

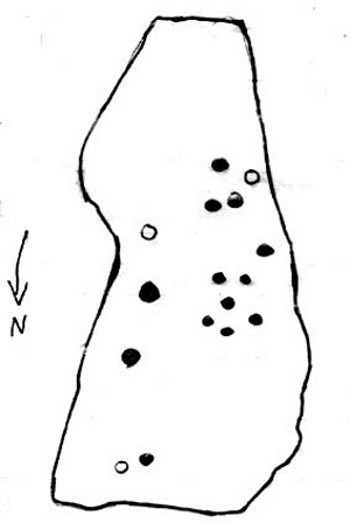

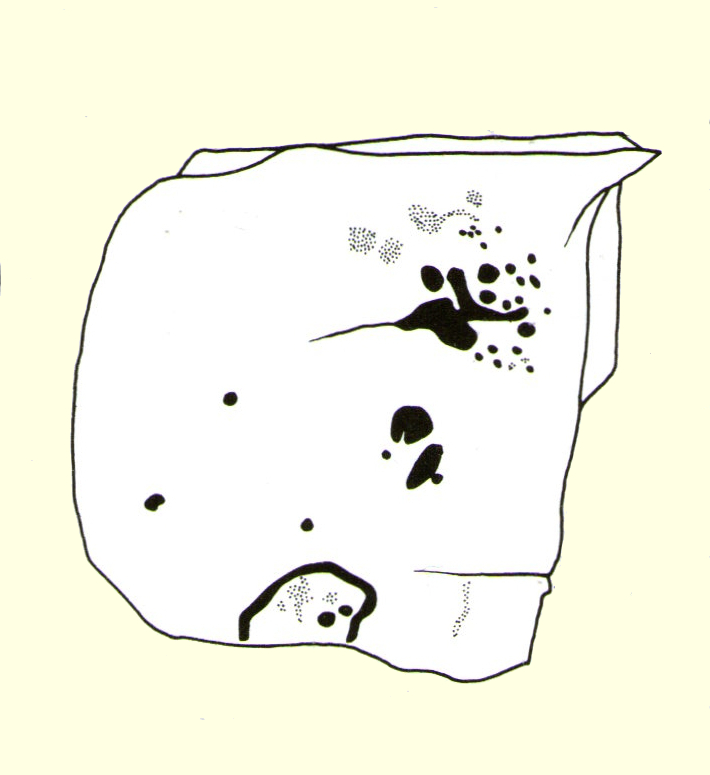

“Panel is carved on W sloping face of a sub-triangular earthfast coarse-grained sandstone boulder 0.81m X 0.50m X 0.38m, the longest axis lying almost exactly N-S. Carving consists of 3 cups, the most N of which is elliptical approx 65mm X 55mm; the central cup is elliptical approx 50mm X 40mm and the most S is circular diameter approx 40mm. On the N edge of the W face is a shallow elliptical depression thought to be of natural origin. There is an area of damage along the ‘crest’ of the boulder close to its S end.

“Carved rock is the most E of five rocks, measuring between 0.70m and 1.15m in length, in very close proximity forming an arc, 3 of which are in the footpath and one of which is resting on a large slab of rock almost completely covered by soil and vegetation.”

And so the small number of cup-marked stones in this woodland slowly grows. One wonders how many more are hidden beneath the roots of the trees—and are all of the lines and cups atop of the great Hanging Stone, a short distant away, all Nature’s handiwork…?

Acknowledgements: Huge thanks for Mike Short for the data, photos and sketch of this carving.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.