Petroglyph: OS Grid Reference – NR 83668 93579

Also Known as:

From Lochgilphead, take the A816 road north for several miles (towards the megalithic paradise of Kilmartin), keeping your eyes peeled for the road-signs saying “Dunadd.” Turn left and park-up a few hundred yards down. Go through the gate and walk up Dunadd. Just before the flattened plateau at the top, a length of smooth stone is accompanied to its side by the deep cup-and-ring of the Dunadd Basin. Three or four yards away, you’ll see the long ‘footprint’.

Archaeology & History

Near the top of Dunadd’s Iron Age ‘fortress’ and overlooking the megalithic paradise of the Kilmartin valley, several man-made carvings are in evidence very close to each other, all with seemingly differing mythic content. This one—the footprint—stands out; but it’s not alone! Faint etchings of at least one other ‘foot’ is clearly visible. The first literary account of it was by Ardrishaig historian R.J. Mapleton (1860), who told,

“There is on the top of Dunadd a mark that strikes me as interesting; it is like a large axe-head, or a rough outline of a foot. My impression is that it may have been the spot on which the chief would place his foot when succeeding to the headship of his tribe. The footmark was always considered among the people here as a mould for an axe-head, and I was rather laughed at for suggesting an inaugurating stone.”

Be that as it may, a few years later the carving had caught the attention of the Scottish Society of Antiquaries. In his article exploring the potential for ritual inaugurations at Dunadd, Captain F.W.L. Thomas (1879) explored, not only the footprint, but the mythic functions of this symbol, looking at parallels with petroglyphs elsewhere in the world where the ‘foot’ was known to be a ritual inauguration symbol (amongst other things). He gave us the first real detailed account of the carving:

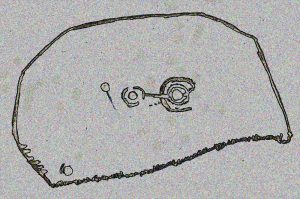

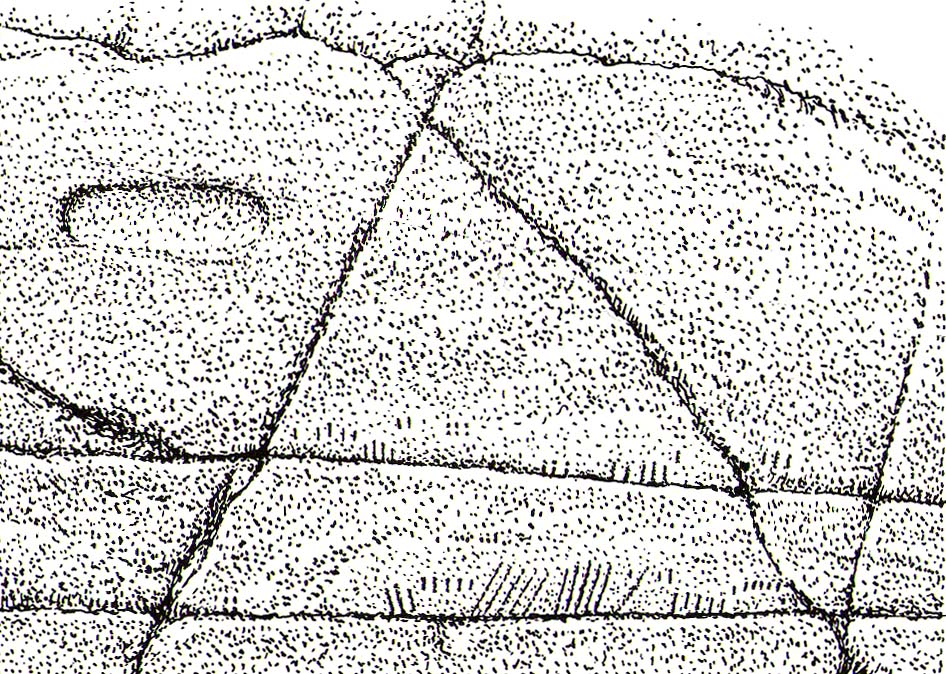

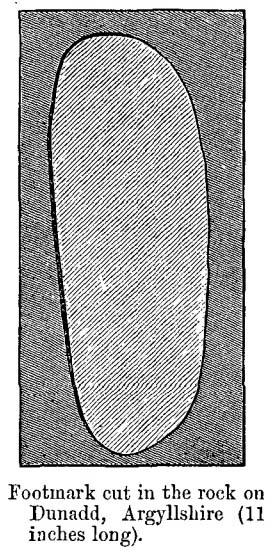

“About 10 or 12 feet below, and to the northward of the highest point, the living rock is smooth, flat and bear of sward, and in it is engraved an impression of a footmark, not of a naked foot, but such as would be made when the foot is clothed by a thick stocking or cuaran… The engravure is for the right foot; and it exactly fitted my right boot. The footmark is sunk half-an-inch deep, with perpendicular sides, the surface is smoothed or polished, and the outline is regular… It has probably been sheltered by the turf until recently. The footmark is 11 inches long, nearly 4½ inches broad where broadest, and 3½ inches across at the heel. When a person stands with his foot in the depression, he looks a little easterly of north.”

A century or so later when the Royal Commission (1988) boys got here, they found not one, but two ‘feet’ carved into the rock! A few feet away, near to the carved boar,

“At the south end of the main rock surface there is the lightly-pecked outline of a shod right foot. 0.24m long and 0.1m in maximum width, with a pronounced taper to the heel. There are further peck marks within the outline, and a sunken footmark was intended but not completed. This print is on almost the same alignment as the more prominent footprint some 2m to the north, which measures 0.27m from NNE to SSW, by 0.1m in maximum width and 25mm in depth. It is somewhat broader at the heel than the incomplete mark, and its sides are straighter.”

They then emphasize how we’re unable to date the footprints, although point out how such carvings are “found in Britain from the Iron Age onwards.” But footprints have be found on other petroglyphs in Scotland (much less in England) and date between the neolithic and Bronze Age periods—but whether Dunadd’s example goes that far back, we cannot say. Extensive excavations occurred at Dunadd between 1980-81 and most of the finds were Iron Age and early medieval in nature (this carving and the cup-and-ring barely got a mention in Lane & Campbell’s [2000] extensive summation). But we may be looking at an evolutionary developmental relationship in symbolism and form, if the traditions of the place have any substance. This is something I’ll return to when writing of the Boar Carving, just a few feet away…

Folklore

The legends behind this seemingly insignificant mark near the top of Dunadd ostensibly echo and relate to the huge cup-and-ring of Dunadd Basin four yards away. I can only repeat what I said in that site profile.

R.J. Mapleton (1860) said that Dunadd was known by local people to be a meeting place of witches and the hill of the fairies, whose amblings in this wondrous landscape are legion. Legends and history intermingle upon and around Dunadd. Separating one from the other can be troublesome as Irish and Scottish Kings, their families and the druids were here. One such character was the ever-present Ossian. Mapleton told:

“From these ancient tales we turn to a much later period of romance, when Finn and his companions had developed into extraordinary and magical proportions; a story is current that when Ossian abode at Dunadd, he was on a day hunting by Lochfyneside; a stag, which his dogs had brought to bay, charged him; Ossian turned and fled. On coming to the hill above Kilmichael village, he leapt clean across the valley to the top of Rudal hill, and a second spring brought him to the top of Dunadd. But on landing on Dunadd he fell on his knee, and stretched out his hands to prevent himself from falling backwards. ‘The mark of a right foot is still pointed out on Rudal hill, and that of the left is quite visible on Dunadd, with impressions of the knee and fingers.’”

As Mr Thomas (1879) clarified:

“The footmark is that of the right foot, and the adjacent rock-basin is the fabulous impression of a knee.”

References:

- Bord, Janet, Footprints in Stone, Heart of Albion Press 2004.

- Campbell, Marion, Mid-Argyll: An Archaeological Guide, Dolphin Press: Glenrothes 1984.

- Campbell, M. & Sanderman, M., “Mid-Argyll: An Archaeological Survey,” in Proceedings of the Society Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 95, 1962.

- Craw, J.H. “Excavations at Dunadd and other Sites,” in Proceedings of the Society Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 64, 1930.

- Lane, Alan & Campbell, Ewan, Dunadd: An Early Dalriadic Capital, Oxbow: Oxford 2000.

- Mapleton, R.J., Handbook for Ardrishaig Crinan Loch Awe and Pass of Brandir, n.p. 1860.

- Morris, Ronald W.B., The Prehistoric Rock Art of Argyll, Dolphin Press: Poole 1977.

- Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments of Scotland, Argyll – Volume 6: Mid-Argyll and Cowal, HMSO: Edinburgh 1988.

- Thomas, F.W.K., “Dunadd, Glassary, Argyleshire: The Place of Inauguaration of the Dalriadic Kings,” in Proceedings of the Society Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 13, 1879.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian