Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – NN 65096 39442 — NEW FIND

Getting Here

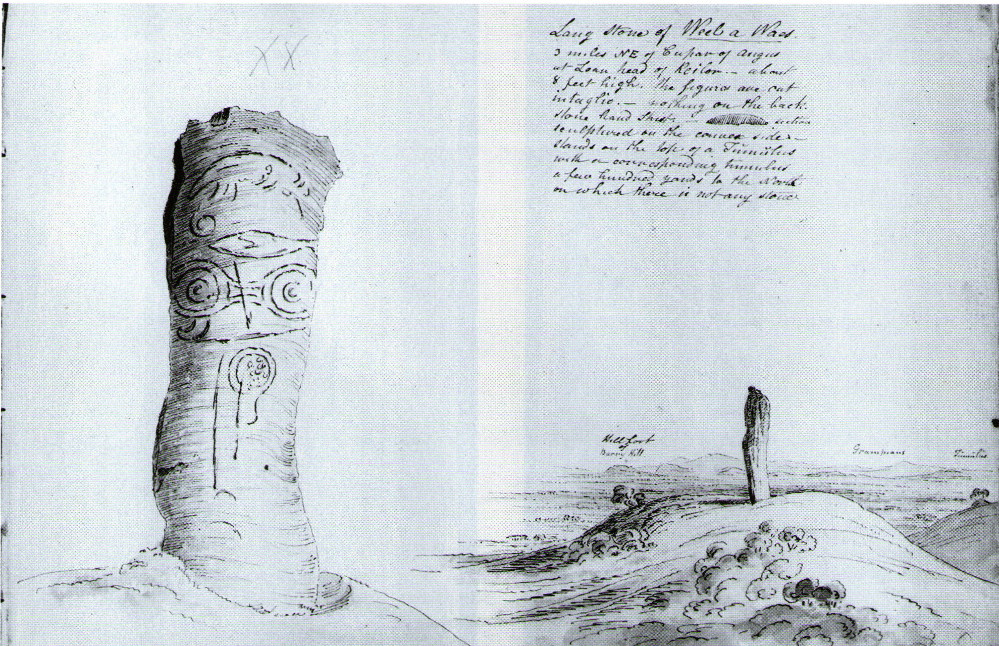

The stone, uncovered

Take the A827 road between Killin and Kenmore and park-up at the entrance to Tombreck. Cross the road and walk up the track that goes up Ben Lawers. As it zigzags uphill, watch out for you being level with the top of the copse of trees several hundred yards west, where a straight long overgrown line of walling runs all the way to the top of the copse. Go along here, and just as you reach the trees, walk uphill for about 50 yards. You’re damn close!

Archaeology & History

Whether you’re into prehistoric carvings or not, this is impressive! It’s one of several with a very similar multiple-ring design to be found along the southern mountain slopes of Ben Lawers. Rediscovered on May 13, 2015, several of us were in search of a known cup-and-ring stone just 260 yards (238m) to the northwest in this Allt a’ Choire Chireinich cluster, but one stone amongst many called my nose to have a closer sniff—and as you can see, the results were damn good!

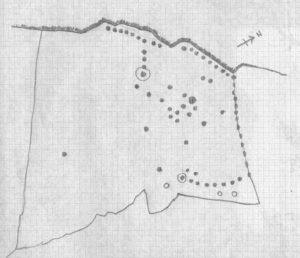

Looking from above

Etched onto a large flat rock perhaps 5-6000 years ago, probably over at least two different seasons, the primary design here is of two sets of multiple-rings: in one case, seven concentric ones emerging from, or surrounding a central cup-marking (more than an inch across); and the other is of at least eight concentric rings emerging from a cup-marking, about half-an-inch across. The largest cup-and-seven-rings is the one near the centre of the stone. Initially I thought this was simply two concentric seven-rings; but the more that I looked through the many photos we’d taken, the more obvious it became that the residue of an eighth ring (possibly more) exist in the smaller-sized concentric system. It must however be pointed out that neither of the concentric carved rings seem to be complete – i.e., they were never finished, either purposefully or otherwise. The largest cup-and-seven-rings is the one near the centre of the stone; with the outer smaller example being half the size of the one in the middle. At first glance, neither of the concentric rings seem complete – and so it turned out when it was enhanced by rain and sun.

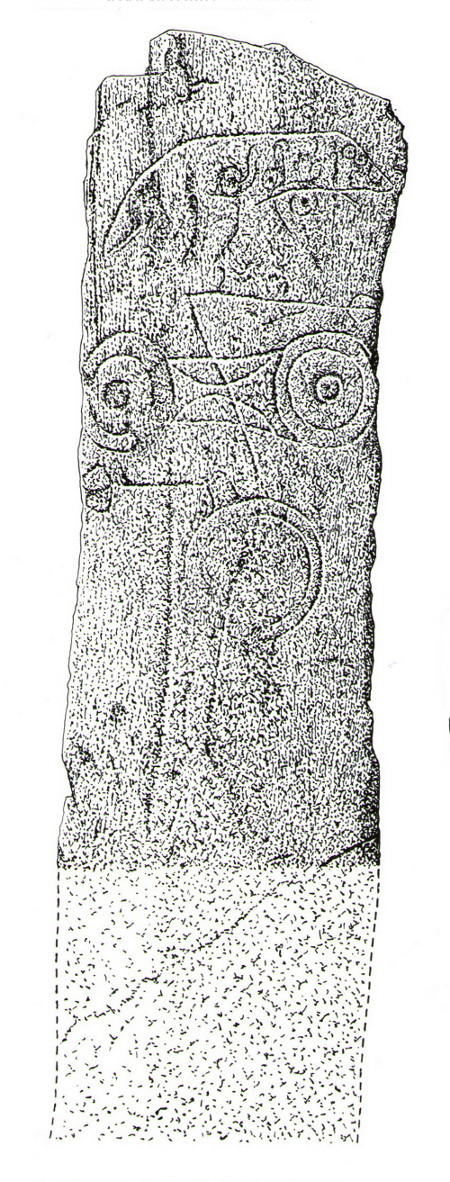

First photo of the double-rings

The large central cup-and-seven-rings has two additional cup-marks within it: one on the outer fifth ring to the southeast, and the other in the outer sixth ring to the west. This western cup-mark is also crossed by a carved line that runs from the first ring outwards to the west and to the edge of the rock, crossing another cup-mark along the way. This particular carved line might be the same one that integrates itself into the first ring, and then re-emerges on is northeastern side, to continue out of the multiple-rings themselves and curve over to the eastern side of the rock. Running roughly north-south through the middle of this larger seven-ring element, a line scarred by Nature is visible which has been pecked by humans on its northern end, only slightly, and running into the covering soil eventually, with no additional features apparent. Another possible carved line seems in evidence running from the centre to the southeastern edge – but this is by no means certain.

The carving, looking north

This large central seven-ringed symbol has been greatly eroded, mainly on its southern sides, where the rings are incomplete, as illustrated in the photos. Yet when the light is right, we can see almost a complete concentric system, with perhaps only the second ring from the centre being incomplete on its eastern side. On the southern sides, the visibility factor is equally troublesome unless lighting conditions are damn good. The northernmost curves, from west to east, are the deepest and clearest of what remains, due to that section of the stone being covered in soil when it was first discovered, lessening the erosion.

Smallest 7-ring section, with cups

Multiple-ring complex & cups

Moving onto the second, smaller concentric set of rings: this is roughly half the size of its counterpart in the middle of the stone. Upon initial investigation you can clearly make out the seven rings, which have faded considerably due to weathering. It seems that this section was never fully completed. And the weathering on this smaller concentric system implies one of two things: either that it was left open to the elements much much longer than its larger seven-ring system, or it was carved much earlier than it. In truth, my feeling on this, is the latter of the two reasons. Adding to this probability is the fact that even more rings—or at least successive concentric carved ‘arcs’—are faintly visible around this more faint system: at least eight are evident, with perhaps as many as thirteen in all (which I think would put it in the record-books!). But we need to visit it again under ideal lighting conditions to see whether there are any more than the definite eight. It is also very obvious that the very edge of the rock here has been broken off at some time, and a section of the carving went with it—probably into the ancient walling below or the derelict village shielings on the mountains slopes above.

Just above the eroded eight-ring section are three archetypal cup-marks close to the very edge of the rock, one above each other in an arc. Of these, the cup that is closest to the eight-rings possesses the faint remains of at least two other partial rings above it, elements of which may actually extend and move into the concentric rings themselves—but this is difficult to say with any certainty. However, if this is the case, we can surmise that this small cup-and-two-rings was carved before its larger tree-ring-looking companion.

Below the smaller seven-ringer is the possibility of a wide cup-and-two-rings: very faint and incomplete. This only seems visible in certain conditions and I’m not 100% convinced of its veracity as yet.

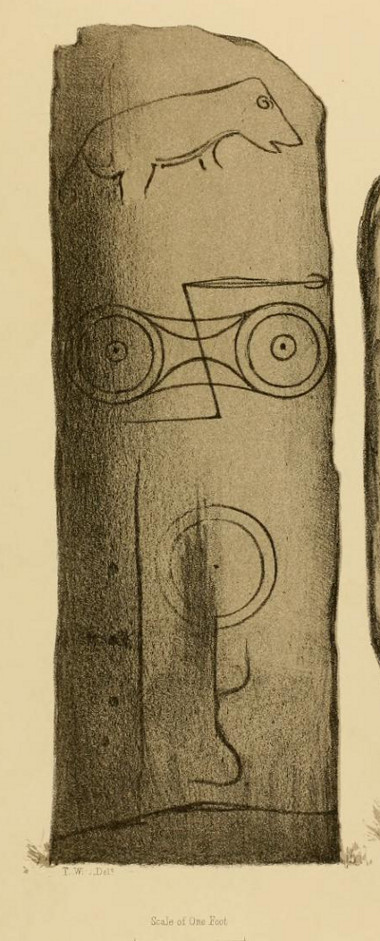

Curious ‘eye’-like symbol

‘Eye’ to the bottom-left

We also found several other singular cup marks inscribed on the rock, all of them beneath the two concentrics, moving closer to the edge of the rock. But a more curious puzzle is an eye-like symbol, or geological feature, on the more eastern side of the stone. It gives the impression of being worked very slightly by humans, but as I’m not a geologist, I’ve gotta say that until it is looked at by someone more competent than me, I aint gonna commit myself to its precise nature. What seems to be a carved line to the left (west) of this geological ‘eye’ may have possible interference patterns pecked towards it. Tis hard to say with any certainty.

So – what is this complex double-seven-ringer?! What does it represent? Sadly we have no ethnological or folklore narratives that can be attributed to the stone since The Clearances occurred. We only have the very similar concentric six- and seven-ringed petroglyphs further down the mountainside to draw comparisons with. We could guess that the position of the stone halfway up Ben Lawers, giving us a superb view of the mountains all around Loch Tay might have some relevance to the carving; but this area was probably forested when these carvings were etched—which throws that one out of the window! We could speculate that the two multiple rings represent the Moon and Sun, with the smaller one being the Moon. They could represent a mythic map of Ben Lawers itself, with the central cup being its peak and outer rings coming down the levels of the mountain. Mountains are renowned in many old cultures as, literally, cosmic centres, from whence gods and supernal deities emerge and reside; and mountains in some parts of the world have been represented by cup-and-ring designs, so we may have a correlate here at Ben Lawers. O.G.S. Crawford (1957) and Julian Cope (1998) would be bedfellows together in their view of it being their Eye Goddess. But it’s all just guesswork. We do know that people were living up here and were carving other petroglyphs along this ridge, some of which occur inside ancient settlements; but the traditions of the people who lived here were finally destroyed by the English in the 19th century, and so any real hope of hearing any old myths, or possible rites that our peasant ancestors with their animistic worldview possessed, has died with them.

Tis a fascinating carving nonetheless—and one worthy of seeking out amongst the many others all along this beautiful mountainside…

References:

- Bernbaum, Edwin, Sacred Mountains of the World, Sierra Club: San Francisco 1990.

- Cope, Julian, The Modern Antiquarian, Thorsons 1998.

- Crawford, O.G.S., The Eye Goddess, Phoenix House: London 1957.

- Eliade, Mircea & Sullivan, Lawrence E., “Center of the World,” in Encyclopedia of Religion – volume 3 (edited by M. Eliade), MacMillan: Farmington Hills 1987.

- Evans-Wentz, W.Y., Cuchuma and Sacred Mountains, Ohio University Press 1980.

- Gillies, William A., In Famed Breadalbane, Munro Press: Perth 1938.

- Michell, John, At the Centre of the World, Thames & Hudson: London 1994.

- Yellowlees, Sonia, Cupmarked Stones in Strathtay, Scotland Magazine: Edinburgh 2004.

Acknowledgements: Huge thanks to Paul Hornby for the use of his photos in this site profile; to Lisa Samson, for her landscape detective work at the site; and to Fraser Harrick, for getting us there again.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian