Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – NO 25290 37378

Getting Here

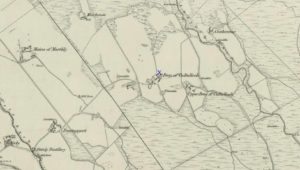

MacRitchie’s 1900 groundplan

Follow the same directions as if you’re visiting the Pitcur (3) souterrain. Once here, you’re standing at the southernmost uncovered section of the monument, where one uncovered passageway bends round and meets up with another open section (“m” on MacRitchie’s plan, right). From here, just to your right, a single large roofing stone joins one side of the open passageway with the other, enabling you to walk across it—and the stone you’d walk across has these very faint carvings on it.

Archaeology & History

Shortly before darkfall a few weeks ago, Nina Harris, Frank Mercer, Paul Hornby and I were just about ready to pack-up and leave the brilliant Pitcur souterrain with its underground chambers and various petroglyphs when, as I walked along one of the open passages beneath one of the monument’s many large capstones, my fingers gently stroked the rock above me, almost unconsciously.

First photo of the carving (by Paul Hornby)

“Was that a faint cup-mark?” I asked myself, fondling gently the smooth stone once more.

Standing eight-feet above me in the long grasses, Mr Hornby was gazing around in his usual way.

“Paul – can you see from up there if this is a cup-marking I’m feeling here?”

Walking onto the edge of the rock itself, he proclaimed, “it looks like it!”

It was indeed! And during the remaining 30 minutes of daylight we found that the single cup-mark had a number of companions on the same stone. With multiple rings! Twas another good day out.

Carving when wet (photo, Frank Mercer)

Looking straight down

Previously unrecorded, this large rounded stone just about covers the space across from one side of the souterrain passage to the other, measuring roughly 6 feet by 4 feet, with its longer axis positioned roughly east-west. It was on the westernmost edge of the stone where I located the first single cup-mark, close to the edge, but there are perhaps 12 others: three of which, as the photos show, are in a straight line from near the west-side of the stone to the upper-middle. On its far eastern edge, another cup-mark is clearly evident; whilst on its southernmost edge is another. It’s the middle and eastern section of the rock that grabs most of the attention. Here we found the very faint rings becoming clearer and clearer as the dust of ages was carefully swept away, eventually giving us vision of carvings that were, in all likelihood, first pecked into the rock in the neolithic period, 4-6000 years ago.

Close-up of the 2 triple-rings

Cup-and-rings at an angle

As we can see, two faint triple-rings exist, each with lines running in/out of them. The eastern concentric system is just about complete and has a small cup-mark on the NW edge of the outer ring. A line that runs out from the central cup meets another carved line which, from some angles, appears to look almost like a bowl beneath the triple rings—but this is unclear. The other triple cup-and-ring, slightly closer to the middle of the stone, has an incomplete outer ring, with evidence of another line running outwards from its central cup. There seems to be a slightly-pecked outline of a single cup-and-ring on the north side of the stone, but this is also unclear.

In truth we need to revisit the site soon, when the lighting gives us a clear idea of what we actually found, because our visit here was cut short by encroaching night and a grey cloudy evening—which are not the best conditions for isolating new petroglyphs!

At least six other petroglyphs exist within the Pitcur Souterrain (3), with the one closest to this (Pitcur 3:3) also used as a roofing stone, covering the deep trench from one side to the other. However, it would appear the petroglyphs on that stone were on its underside, as the erosion on it is negligible, away from the elements—unlike this one! Another capstone that was also turned over (Pitcur 3:4) was found to possess more cup-and-rings, again on the underside of the stone.

This carving was probably executed 2-3000 years before the souterrain came into existence, and as a result of this we’re unsure as to the original location of the stone—but it was probably close by. It might have originally been a carved standing stone, re-used here; or been part of a lost prehistoric tomb; or even a loose earthfast rock (though this is the least likely of the three). Why it was used, and whether it retained any sense of the original meaning when it was re-positioned into the present construction, is a relevant question. In all likelihood some of the original mythic element—or a morphed development of its original animistic narrative–was probably a functional ingredient of importance to the souterrain builders, 2-3000 years after the carving had been made.

A superb site!

References:

- Wainwright, F T., The Souterrains of Southern Pictland, RKP: London 1963.

Acknowledgements: This site profile would not have been made possible were it not for the huge help of Nina Harris, Frank Mercer & Paul Hornby. Huge thanks to you all, both for the excursion and use of your photos in this site profile. 🙂

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian