Cairns: OS Grid Reference – SD 856 733

Also known as:

- Giant’s Grave

Easy enough to get to – and a lovely place to behold for an amble! From Settle, take the B6479 road up to Horton-in-Ribblesdale (ask a local if you’re too dumb to find it!), turning right at Stainforth and up the single-track road towards Pen-y-Ghent. Keep yer eyes peeled for Rainscar – you’ve about a mile to go. If you end up at Pen-y-Ghent House you’ve gone past ’em. Turn back for 2-300 yards. It’s on the right-hand side of the road as you’re coming up, about 100 yards up the footpath.

Archaeology & History

The earliest description I’ve found of this is in Terence Dunham Whitaker’s History and Antiquities of Craven (1878), where he reckoned the remains here to be of Danish origin. The same thing was professed by the southerner, archdeacon W. Boyd, who said as such to the local people hereabouts more than 100 years ago, but they thought him a bit stupid and laughed at his notions! (though it does seem that Boyd wasn’t liked locally, tending to think himself better than the local people, who told him very little of local lore and legend) Describing the remains, Whitaker said there were skeletons found in the tombs:

“The bodies have been inclosed in a sort of rude Kist vaen, consisting of limestone pitched on edge, within which they appear to have been artificially bedded in peat earth.”

But Harry Speight (1892) doubted this, saying that Whitaker never even visited the site! When he went here he told us that,

“What is left at present are a few mounds of earth, the largest, which is divided into two, and lies north and south, measures about 28 feet by 25 feet. There is another apparent grave-mound on the east side of it, and again to the north is an oblong excavation or trench, 7 feet wide and nearly 30 feet long, in which several bodies or coffins may have been deposited. Several large oblong stones lay flay upon the ground beside the graves, but these were removed a few years ago and degraded to the service of gate-posts.”

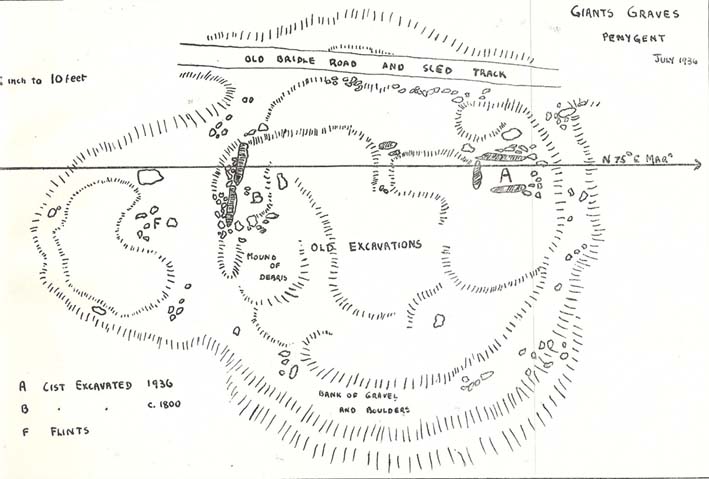

The site was excavated in June 1936 by Arthur Raistrick and W. Bennett (1937) after they had been badly damaged and the stones robbed for walling and other profane building operations. Herein were found two burial cists with fragments of human bones in each tomb. In Bennett’s short account he told:

“The site consists of a nearly circular bank, about eight feet wide, and in parts two feet high, surrounding a much disturbed area. Within the area are the remains of two cists and a number of hollows that certainly represent other similar structures. The farmer tells of the removal of more than twenty large stones from these hollows, for use as gateposts, wall throughs and drain covers.* The bank encloses an area fifty-four feet east to west…and fifty feet north to south. At the west end there is a smaller bank, roughly in form of a circular apse, extending a further thirty feet. Many large boulders and vast quantities of smaller stone are incorporated in the bank.

“Near the east end, with its axis bearing N75E, is a cist — three stones in position. This was cleared to a depth of eighteen inches, and though no floor stone was present, among the sifted soil were found (i) broken bones, including parts of humourus, axis, vertebrae, ulna, ribs and cranium, all human; (ii) five teeth — two molars, one wisdom tooth, and two incisors, which appear to represent tow individuals. Sir Arthur Keith reports that the bones submitted to his examination may represent more than one adult person, and there is also a fragment of a child’s tibia. Most of the limb bones belong to a man of medium stature… He suggests from the condition of the bones a person of the Iron Age. While this is possible with a secondary interment in the area, it is rather unlikely, as all the bones came from within the built cists, and not from the earthen part of the mound, where secondary burials would be expected.

“At the west end are two large stones, the side stones of cists or of a chamber. The ground in front of them has been excavated many years ago…and partially refilled with boulders… Within the small extension on the west a trial excavation showed eighteen inches to two feet of random boulders, and beneath them, on the old sub-soil surface, two inches of fine grey sand, with two small flints — one of them a well-worked blade. These probably pre-date the construction of the circle.

“The whole site is suggestive of a multiple cist burial mound, or even a “passage grave” type. The obvious hollows, from which many of the larger stones have been lifted, are aligned in a parallel series, along an axis N75E, directed towards the two remaining large stones at the west, which may be part of a chamber wall and not part of a cist.”

Recent archaeological analysis has suggested these may be the remains of an old chambered cairn, although there is today far too much damage that’s been done to give us an accurate portrayal of what this originally looked like. The Dawson Close prehistoric settlement is less than half-a-mile further up the ridge.

Folklore

The folklore here is simple: these are the graves of giants who lived in the valley of Littondale in ancient times.

References:

- Bennett, Walter, ‘Giants’ Graves, Penyghent,’ in Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, part 131, 1937.

- Boyd, W. & Shuffrey, W.A., Littondale Past and Present, Richard Jackson: Leeds 1893.

- Feather, Stuart & Manby, T.G., ‘Prehistoric Chambered Tombs of the Pennines,’ in YAJ 42, 1970.

- Speight, Harry, The Craven and North-West Yorkshire Highlands, Elliott Stock: London 1892.

- Whitaker, Thomas Dunham, History and Antiquities of the Deanery of Craven, Joseph Dodgson: Leeds 1878 (3rd edition).

* It might be worthwhile exploring the local gateposts and walls to see if any of these covering stones had cup-and-rings carved on them, as was traditional in many parts of Yorkshire and northern England.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.