Earthworks: OS Grid References – SE 0514 3627

Also Known as:

- Blood Dykes

Dead easy this one! On the Keighley-Halifax A629 road, about 500 yards south past Flappit Spring (public house), there’s a small road to your right. Walk on here for 200 yards and look in the field to your right. If the grass is long you might struggle to see it, but gerrin the field and it runs right up against the wall. Y’ can’t miss it really! You can park up a coupla hundred yards down the A629 main road, by the old quarry, and walk back to get here.

Archaeology & History

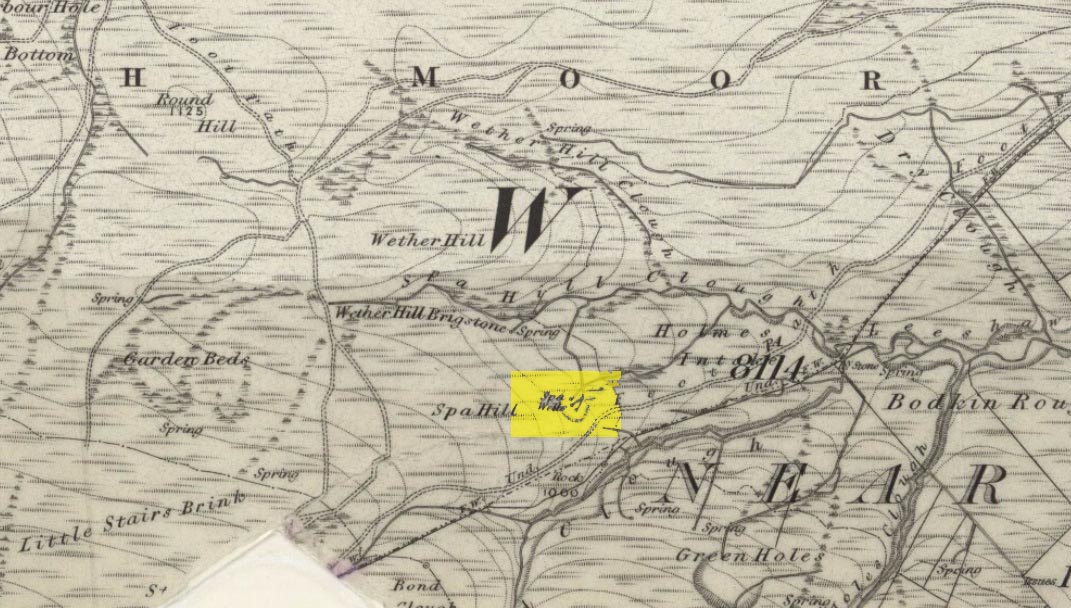

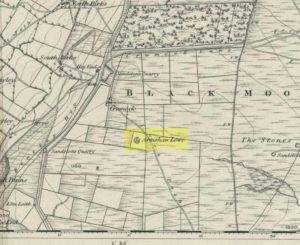

Although I’ve earlier described this as “nowt much to look at,” the more I come here, the more I like the place (sad aren’t !!?). The hard-core archaeology folks amidst you should like it aswell. Not to be confused with the site of the same name a mile to the south of here, this large earthwork was shown on the 1852 OS-map as a complete ring, which is also confirmed in old folklore; and a survey done by Bradford University in the late 1970s indicated a complete circle was once in evidence. To view this for yourself: if you type the OS grid-reference into Google maps, you’ll see from the aerial image that a complete ring was indeed here at sometime in the not-too-distant past.

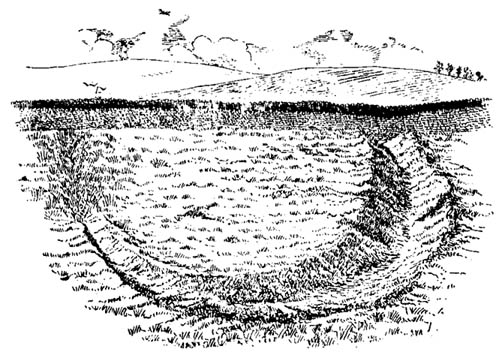

Today however – indeed, since William Keighley described it 1858 – there’s only a shallow, semi-circular ditch to be seen in the fields. But despite this, its remains have brought it to the literary attention of about a dozen writers – though we still don’t know exactly what it was! The best conjecture is by the archaeologist Bernard Barnes (1982), who thinks it best to describe as a enclosure or earthwork dating from the Bronze Age. Eighty feet across and covering more than 1.5 acres, an excavation of the site in 1911 found nothing to explain its status.

One of the first descriptions of this site comes from the pen of the industrial Bradford historian, John James in 1876 (though Hearne, Leland and Richardson describe it in brief much earlier). Talking of the sparsity of prehistoric remains in the region (ancient history wasn’t his forte!), he said, “I know of no British remains in the parish that are not equivocal, unless a small earth-work lying to the westward of Cullingworth may be considered of that class.”

Indeed it is! He continued:

“It is situated on a gentle slope, about two hundred yards from a place called Flappit Springs, on the right-hand side of the road leading thence to Halifax. The form has been circular. (my italics) The greater part of it to the south has been destroyed by the plough. I took several measurements of that part which remains, but have mislaid the memoranda I then made; I however estimate the diameter to have been about 50 yards. The ditch to the westward is very perfect. It is about two yards deep and three wide; with the earth thrown up in the form of a rampart on the inner side. The remain is less perfect to the eastward.”

James then speculates on the nature of the site, thinking it to be “one of a line of forts erected by the Brigantes…to prevent the inroads of the Sistuntii.” Intriguing idea!

A few years later when William Cudworth (1876) visited the site, he described:

“At present there only remains about one-fourth part of a circle representing the appearance of a considerable earthwork or rampart. The remainder has been cut away by the construction of the road leading to the allotments.”

Echoing Mr James’ sentiments, Cudworth also suggested “it may have been an enclosure to guard their cattle, while in summer they grazed on the vast slope on which it stands.” Y’ never know…

A visit to the place on October 21 2007, found not only a profusion of mushrooms scattering the field (varying species of Amanita, Lycoperdon, Panaeolina, Psilocybes, etc), and the remnants of two old stone buildings 20 yards of the NE side, but a distinctive ‘entrance’ on the northern side of the ring, which gave the slight impression of it being a possible henge monument. It’s certainly big enough! All traces of the southern-side of the ring however, have been ploughed out.

The views from here are quite excellent, nearly all the way round. You’re knocking-on a 1000 feet above sea level and the high hills of Baildon, Ilkley, Ogden Moor and the Oxenhope windmills are your mark-points. There’s one odd thing to think about aswell: if this is a prehistoric site, it’s pretty much an isolated one according to the archaeo-catalogue – and as we know only too well, that aint the rule of things. We’ve got adjacent moorlands south and west of here, very close by. Likelihood is, there’s undiscovered stuff to be foraged for hereabouts…

Folklore

An old folk-name given to this ring is the Blood Dykes, which is supposed to relate to the place being the site of a great battle.

References:

- Barnes, Bernard, Man and the Changing Landscape, Eaton: Merseyside 1982.

- Bennett, Paul, The Old Stones of Elmet, Capall Bann: Milverton 2001.

- Cudworth, William, Round about Bradford, Thomas Brear: Bradford 1876.

- Elgee, Frank & Harriett, The Archaeology of Yorkshire, Methuen: London 1933.

- Forshaw, C.F., ‘Castlestead, near Cullingworth,’ in Yorkshire Notes and Queries – volume 4, H.C. Derwent: Bradford 1908.

- James, John, The History and Topography of Bradford, Longmans: London 1876.

- Keighley, J.J., ‘The Prehistoric Period,’ in Faull & Moorhouse’s, West Yorkshire: An Archaeological Survey to AD 1500 – volume 1, WYMCC: Wakefield 1981.

- Keighley, William, Keighley, Past and Present, Arthur Hall: Keighley 1858.

- Speight, Harry, Chronicles and Stories of Bingley and District, Elliott Stock: London 1898.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.