Standing Stone: OS Grid Reference – SD 9711 3826

Also known as:

- Hanging Stone

- Standing Stone

- Waterscheddles Cross

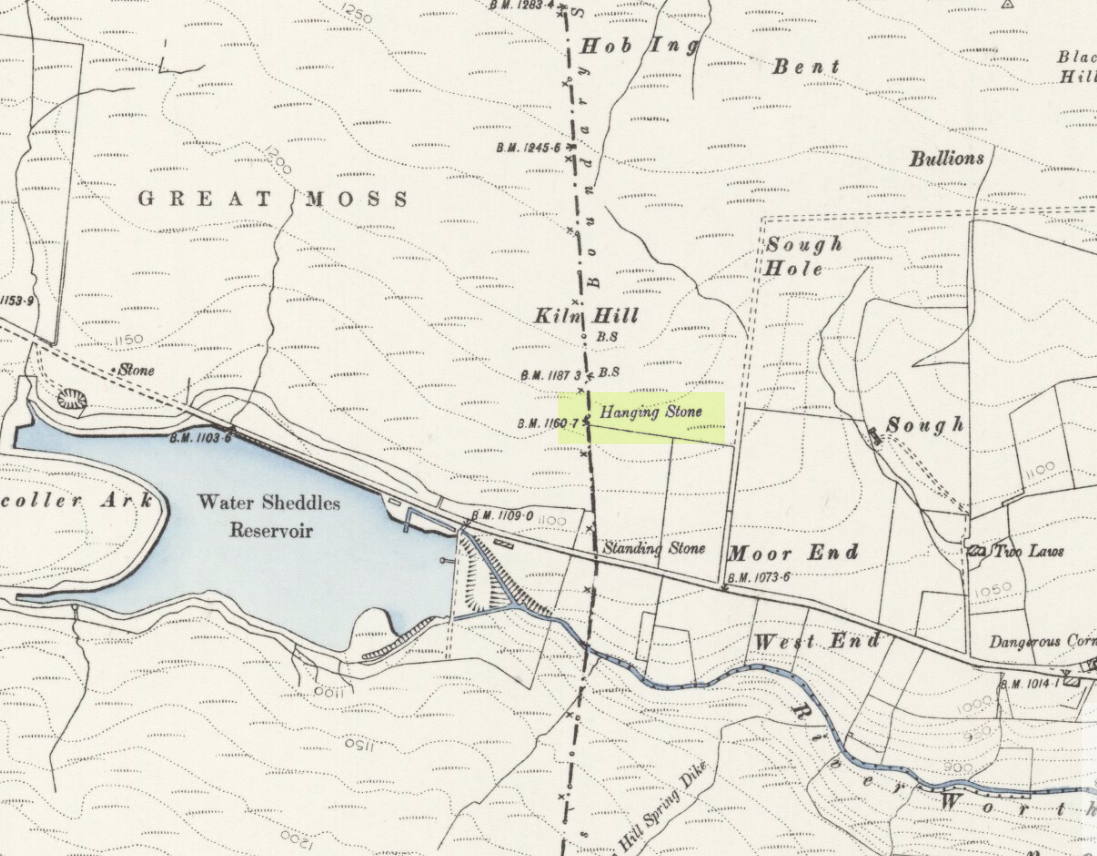

Pretty easy to find. Go along the Oakworth-Wycoller road, between Keighley and Colne, high up on the moors. When you get to the Water Sheddles Reservoir right by the roadside (y’ can’t miss it), stop! On the other side of the road walk onto the moor, heading for the walling a coupla hundred yards to your east (right). Where the corner edge of the walling ends, your standing stone is right in front of you! If for some reason you can’t see it, wander about – though beware the very boggy ground all round here.

Archaeology & History

This seven-foot tall monolith, leaning to one side thanks to the regularly water-logged peat beneath its feet, stands on the Yorkshire-Lancashire. It is locally known as the Hanging Stone and the Standing Stone, but the name ‘Water Sheddles’ is a bittova puzzle. The place-names authority, A.H. Smith (1961) thinks it may derive from the middle-english word, shadel, being a ‘parting of the waters’ – which is pretty good in terms of its position in the landscape and the boggy situation around it. But ‘sheddle’ was also a well-used local dialect word, though it had several meanings and it’s difficult to say whether any of them would apply to this old stone. Invariably relating to pedlars, swindling or dodgy dealings, it was also used to mean a singer, or someone who rang bells, or a schedule, aswell as to shuffle when walking. Perhaps one or more of these meanings tells of events that might have secretly have been done here by local people, but no records say as such — so for the time being I’ll stick with Mr Smith’s interpretation of the word! Up until the year 1618 it was known simply as just a ‘standing stone’, when it seems that the words “Hanging Stone or Water Sheddles Cross” were thereafter carved on its west-face, as the photo below shows.

Whether or not this stone is prehistoric has been open to conjecture from various quarter over the years. Is it not just an old boundary stone, erected in early medieval times? Or perhaps a primitive christian relic? Certainly the stone was referred to as “le Waterschedles crosse”, as well as “crucem”, in an early record describing the boundaries of the parish of Whalley, dating from around the 15th century. This has led some historians to think that the monolith we see today is simply a primitive cross. However, sticking crosses on moortops or along old boundaries tended to be a policy which the Church adopted as a means to ‘convert’ or christianize the more ancient heathen sites. It seems probable in this case that an old wooden cross represented the ‘crucem‘ which the monks described in the early Whalley parish records.

This monolith likely predates any christian relic that might once have stood nearby; although the carving of a ‘cross’ on the head of the stone may have supplemented the loss of the earlier wooden one. But it seems likely that this carved ‘cross’ was done at a later date than the description of the ‘crucem‘ in the parish records — probably a couple of centuries later, when a boundary dispute was opened, in 1614, about a query on the precise whereabouts of the Yorkshire-Lancashire boundary. After several years, as John Thornhill (1989) wrote,

“the matter was resolved on the grounds that the vast Lancastrian parish of Whalley had claimed territorial jurisdiction as far east as the Hanging Stone, thus the county boundary was fixed on the Watersheddles Cross.”

Certainly the stone hasn’t changed in the last hundred years, as we can tell from a description of it by Henry Taylor (1906), who said:

“The remains consist of a rough block of stone, leaning at an angle of about forty-five degrees against a projecting rock. The top end has been shaped into the form of an octagon, on the face of which a raised cross is to be seen. The stone is about six feet long and two feet wide, tapering to eleven inches square at the upper end, and appears once to have stood upright. Some local authorities have cut on it the words, ‘Hanging Stone or Waterscheddles Cross.'”

So is it an authentic prehistoric standing stone? Tis hard to say for certain I’m afraid. It seems probable – but perhaps no more probable than the smaller Great Moss Standing Stone found just a couple of hundred yards away in the heather to the west, on the Lancashire side of the boundary. Tis a lovely bitta moorland though, with a host of lost folktales and forgotten archaeologies…

References:

- Bennett, Paul, The Old Stones of Elmet, Capall Bann: Milverton 2001.

- Brigg, J.J., ‘A Disputed County Boundary”, in Bradford Antiquary, 2nd Series, no.8, 1933.

- Smith, A.H., The Place-Names of the West Riding of Yorkshire – volume 6, Cambridge University Press 1961.

- Taylor, Henry,The Ancient Crosses and Holy Wells of Lancashire, Sherratt & Hughes: Manchester 1906.

- Thornhill, John, ‘On the Bradford District’s Western Boundary,’ in Bradford Antiquary, 3rd Series, vol.4, 1989.

- Wright, Joseph, English Dialect Dictionary – volume 5, Henry Frowde: Oxford 1905.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian