Sacred Tree: OS Grid Reference – SP 964 079

Archaeology & History

About mile south of Northchurch, on the far side of the A41 dual carriageway, somewhere past the old crossroads (or perhaps even at the crossing) an ancient tree lived—and truly lived in the minds of local people, for perhaps a thousand years or so. Mentioned in the Lay Subsidy Rolls in 1307, the Cross Oak gave its name to the old building that once stood in the trees and the hill itself, at the place now known as Oak Corner. Whether or not a “cross” of any form was set up by this old oak, records are silent on the matter. Its heathen ways however, were pretty renowned! (a plaque should be mounted here)

Folklore

The first reference I’ve found of this place is in William Black’s (1883) folklore survey where he told that “certain oak trees at Berkhampstead, in Hertfordshire, were long famous for the cure of ague”—ague being an intense fever or even malaria. But a few years later when the local historian Henry Nash (1890) wrote about this place, he told that there was only one tree that was renowned for such curative traditions, that being the Cross Oak. He gave us the longest account of the place, coming from the old tongues who knew of it when they were young—and it had it’s very own ritual which, if abided by, would cure a person of their malady. “The legend ran thus”, wrote Mr Nash:

“Any one suffering from this disease was to proceed, with the assistance of a friend, to the old oak tree, known as Cross Oak, then to bore a small hole in the said tree, gather up a lock of the patient’s hair and make it fast in the hole with a peg, the patient then to tear himself from the tree, leaving the lock behind, and the disease was to disappear.

“This process was found to be rather a trying one for a weak patient, and by some authority unknown the practice was considerably modified. It was found to be equally efficacious to remove a lock of hair by gentle means, and convey it to the tree and peg it in securely, and with the necessary amount of faith the result was generally satisfactory. This is no mere fiction, as the old tree with its innumerable peg-holes was able to testify. This celebrated tree, like many other celebrities, has vanished, and another occupies its place, but whether it possesses the same healing virtues as its predecessor is doubtful. It is however a curious coincidence, that the bane and the antidote have passed away together.”

The lore of this magickal tree even found its way into one of J.G. Frazer’s (1933) volumes of The Golden Bough, where he told how the “transference of the malady to the tree was simple but painful.”

Traditions such as this are found in many aboriginal cultures from different parts of the world, where the spirit of the tree (or stone, or well…) will take on the illness of the person for an offering from the afflicted person: basic sympathetic magick, as it’s known. Our Earth is alive!

References:

- Black, William G., Folk Medicine, Folk-lore Society: London 1883.

- Frazer, James G., The Scapegoat, MacMillan: London 1933.

- Jones-Baker, Doris, The Folklore of Hertfordshire, B.T. Batsford: London 1977.

- Nash, Henry, Reminiscences of Berkhamsted, W. Cooper & Nephews: Berkhamsted 1890.

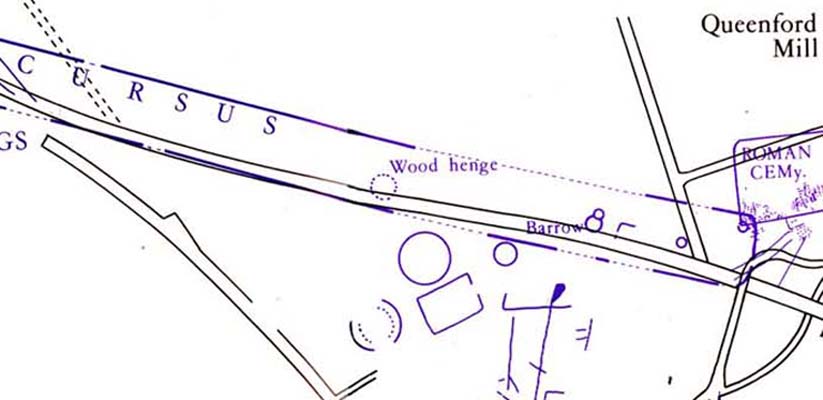

Acknowledgements: Huge thanks for use of the Ordnance Survey map in this site profile, reproduced with the kind permission of the National Library of Scotland.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.