Legendary Stone: OS Grid Reference – NY 893 680

Archaeology & History

Thought to have been destroyed in the 19th century, folklorists and historians alike didn’t seem to be able to locate this little-known folklore relic, which is still alive and well in one of the fields by the village. The exact nature of the stone isn’t known for certain. Legend reputes it to have been one of the four boundary stones which gave the village its name; it was also said that they were Roman altars and the Fairy Stone was one of them, which was moved from the village boundary during the Rebellion of 1715 and placed nearer the centre.

Folklorist M.C. Balfour (1904) seemed to think that stone had gone when he wrote about it. Writing about it in the past tense, he told,

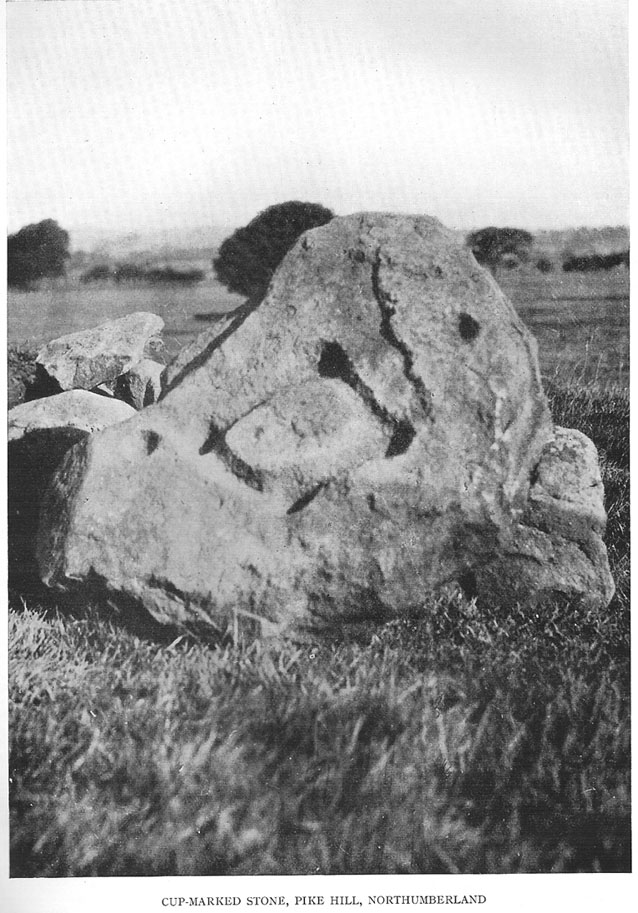

“The Fairy Stone however, certainly had an existence, for a person, 80 years of age, remembered its situation to the south of the village, near the old road, and that it was squared, and had a square “cistern hewn out of its top,” which was called the Fairy Trough, and traditionally said to have had a pillar fixed in it.”

But when former Ley Hunter editor Paul Screeton (1982) came looking for the stone in the late 1970s, he was fortunate in coming across an old local:

“Some time ago while looking for the Fairy Stone at Fourstones…I came across a farmer who pointed it out and remarked that a few years previously when the road was widened the local lengthsman made sure it was not destroyed, though it had to be moved a short distance.”

Folklore

Of the four boundary stones surrounding the village, they were “supposed to have been formed to hold holy water,” said Balfour (1904). But the title Fairy Stone given to one of them had this tale to account for it:

“A couple of miles or more down the South Tyne is Fourstones, so called because of four stones, said to have been Roman altars, having been used to mark its boundaries. A romantic use was made of one of these stones in the early days of “The Fifteen.” Every evening, as dusk fell, a little figure, clad in green, stole up to the ancient altar, which had been slightly hollowed out, and, taking out a packet, laid another in its place. The mysterious packets, placed there so secretly, were letters from the Jacobites of the neighbourhood to each other; and the little figure in green was a boy who acted as messenger for them. No wonder that the people of the district gave this altar the name of the ‘Fairy Stone’.”

References:

- Balfour, M.C., Country Folk-lore volume 4: Examples of Printed Folk-lore Concerning Northumberland, David Nutt: London 1904.

- Screeton, Paul, “The Long Man of Wilmington,” in The Ley Hunter, no.92, 1982.

- Terry, Jean F., Northumberland Yesterday and Today, Andrew Reid: Newcastle 1913.

- Watson, Godfrey, Northumberland Place Names, Sandhill: Morpeth 1995.

Acknowledgements: Big thanks to Paul Screeton for the grid-reference!

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian