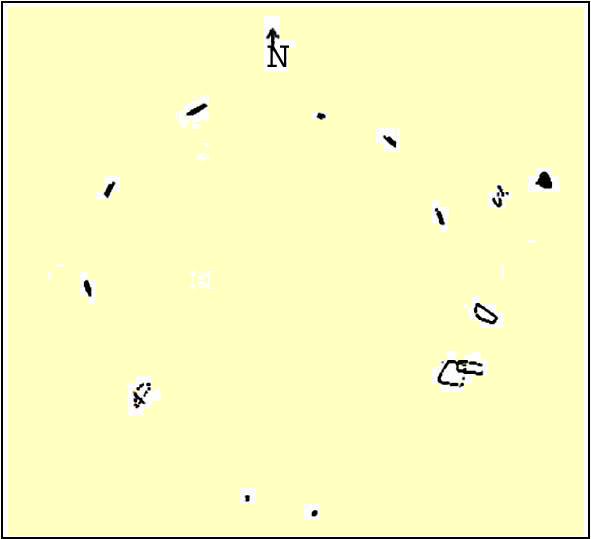

Tumuli (destroyed?): OS Grid References – SE 211 642

Take the road up to Brimham Rocks from Summerbridge; crossing the little crossroads, then keep your eyes peeled for the singular farmhouse on your right. Just beyond this, on your right, you’ll notice some small moorland opens up and reaches gently down the slope for some distance. Go along the footpath for 100 yards or so, then into the heather to your right, for 60 yards or so (as if you walking towards the farmhouse and small crags). This is where the following sites could be found. (when we visited Brimham recently, unfortunately sunfall stopped us having a proper wander here, so the status of the site/s remains unknown to us)

Archaeology & History

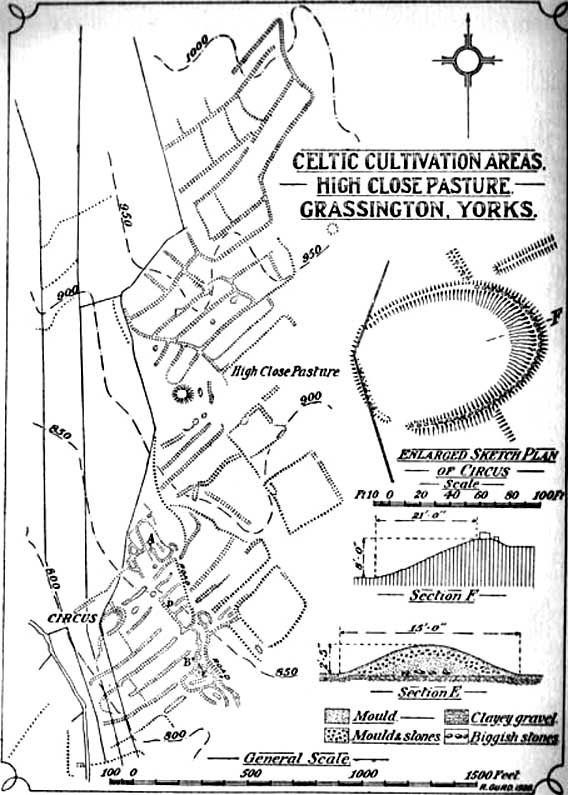

This little-known and possibly destroyed prehistoric site — less than a mile north of Standing Stone Hill and just a coupla hundred yards south of the legendary Brimham Rocks — has been described by several antiquarians from the early 19th century onwards. It’s an intriguing place, deserving of much greater antiquarian attention. Ely Hargrove (1809) appears to be the first who mentions prehistoric tombs here, though his sense of direction implies another site (unless he just got that part of it wrong?). Along with “several small tumuli or carns” near another section of Brimham Rocks themselves, he told there to be,

“Several large tumuli; one of which about 80 yards west of the great Cannon, measures 150 feet in circumference. It is worth remarking that the place where most of these tumuli are found is, at this day, called Graffa Plain, i.e., the Plain of Graves.”

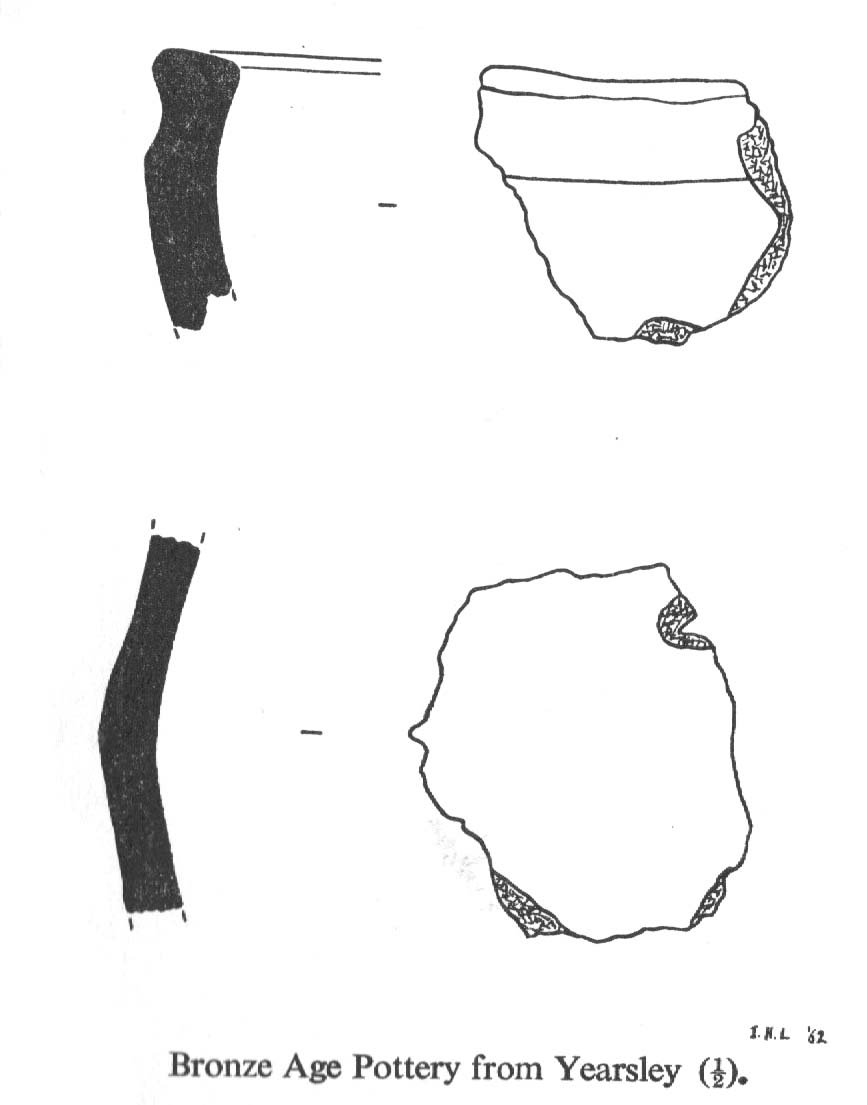

These ‘tumuli’ were again mentioned briefly in passing by one ‘D.N.H.’ in the Gentleman’s Magazine of November 1823. The great Knaresborough historian William Grainge also described cairns here. They were then highlighted on the very first Ordnance Survey of the region in the 1850s and shown as “Supposed tumuli.” Eventually, at the turn of the 20th Century, they were explored at the behest of the local land-owner by Mr L.A. Armstrong. His description of what they found here is intriguing and well worth reproducing in full:

“By permission of the Right Hon. Lord Grantley, I was enabled to make a careful examination of two of the ancient burial mounds of ‘ Graff a Plain,’ Brimham Moor, on Tuesday, August 4th, 1908.

“Mound No. 1, of circular form, and about 12′ o” in diameter, is situated about 150 yards north-west of the first large group of rocks, upon the south-eastern boundary of the moor, and about 50 yards south-east of the trackway leading to ‘ Riva Hill Farm,’ and it occupies the summit of a slight hillock, upon a comparatively level portion of the heath, which rises rapidly to the south of it in a bold sweep, terminating in the outstanding rocks of Graffa Crags and Brimham Beacon.

“The entire absence of any heather upon the mound, and the profusion of bright green bilberry plants which covered it and at the same time rendered its outline more noticeable, told plainly of a different character of subsoil from that of the surrounding moor ; but prominent as the mound appeared, its actual elevation was deceptive, being barely two feet above the natural level, and the uneven character of the upper surface suggested previous disturbance to be more than probable. A few attempts to pierce the crown, however, proved it to be a cairn, constructed of large stones, and accounted for the prolific growth of the rock-loving bilberry which overspread it, as well as for the uneven character of the surface.

“The thick green covering was carefully stripped off in lengths and placed on one side, and the few inches of vegetable earth removed, revealing the cairn in an almost perfect state, formed of a series of large stones placed methodically in concentric rings, each stone slightly inclined towards the centre, and the whole mass interlocked together by their own weight. Large stones were placed around the outside forming the enclosing circle, which is almost invariably found in the case of earth-built tumuli, and a few of these had been visible before the covering was stripped.

“The construction of the cairn rendered it necessary to remove the stones from the outer ring first, and to work gradually towards the centre where the burial, if such existed, might be expected to lie. This proved no easy task, as the stones were so tightly wedged, and had each apparently been specially selected for the purpose. Almost without exception, they were about a foot in diameter, oblong or oval in form, and three to five inches in thickness, with flat surfaces and rounded edges. No marks of tools were visible on any, but all alike were either water-worn, or had been especially rubbed to their present form. The stone itself was the Millstone Grit of the surrounding moor, but fragments of stone of the form composing the cairn are not now to be found thereon readily, although a careful search might reveal such. Personally I am inclined to think that they have been transported from a considerable distance; that great care has been exercised in their selection is indisputable.

“When nearing the inner radius of the cairn, small fragments of charcoal were noticeable, but they were by no means in large quantities. There was also a layer of fine grey sand an inch or two in depth, which had apparently been spread over the natural surface of the ground, and the stones bedded therein. Sand of this kind is abundant in the vicinity of the rocks upon the moor.

“In the centre, large pieces of stone were piled around a rough circle of about 3′ 6” extreme diameter, and within these, large and small stones, all of the form previously noticed, were laid more or less upon their flat surfaces, and amongst them the grey sand and charcoal were very evident; pieces of the latter up to an inch square, being found.

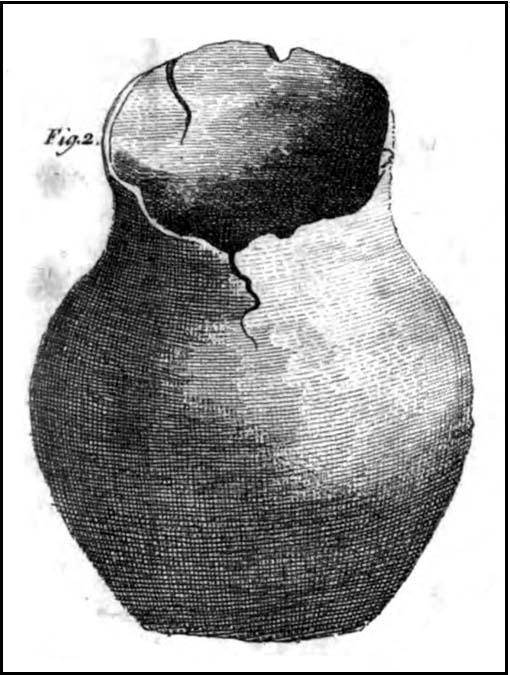

“Upon the gradual removal of this central mass of stones, the presence of the unmistakable black ‘barrow earth’ became evident in a slight layer, perhaps an inch or an inch and a half in thickness, and spread over the whole area within the inner ring, the bottom of which had been paved with large flat stones. Amongst this earth very slight traces of a greyish white paste-like substance were”] visible, probably the decomposed remains of the bones after calcination. The deposit was carefully gathered together. Its removal bared the large stones forming the bottom of the grave, and these proved to be two in number, the largest being about 2′ o” across, and of a somewhat angular form ; strikingly different to those composing the cairn itself, for the edges were rough fractures, not rounded in any way. Apparently the surface soil had been removed from the ground upon which the cairn was built, for the upper face of the two stones forming the bottom was level with the natural ground surface adjoining, so far as could be ascertained, and these had apparently been laid down for the reception of the deposited remains.

“As there was every reason to believe that some portion of the ashes might have been placed in an urn, efforts were made to raise the stones above mentioned in hopes of a discovery. This was by no means easy, but by care and perseverance, it was at last accomplished, but only to meet with disappointment. Immediately beneath was a slight layer of ashes upon the natural ground surface, which latter showed very evident signs of fire, the bright yellow sand composing the substratum being calcined to a dark red colour for quite 2” in depth. This sand was very stiff and compact. The most diligent search failed to reveal any trace of a hole or other disturbance at any point, or of any implements which might have accompanied the body, either upon the surface or amidst the cairn.

“One stone found amidst those immediately covering the deposit, was remarkable because entirely different from all the remainder composing the cairn, and appeared to have been shaped with some definite object in view. It was a fragment of hard sandstone, in the form of a truncated pyramid, the sides and top being roughly fractured to shape, but the base was quite smooth, and bore marks of friction. The base measured 6″ x 5″, and the height about 4½”. This might have been used as a crushing and grinding stone for grain, or for rubbing purposes, but careful search failed to reveal its companion slab. With this exception, nothing was found that could be considered as having been fashioned for use, and there was nothing to throw any light upon the probable period of the cairn’s erection.

“The second tumulus examined is situated about 100 yards south-west of the first. It was of rather irregular shape, and appeared to have been somewhat disturbed, but the original diameter had probably been about 9′ o”. Upon examination, it also proved to be of the cairn type, and apparently similar to that previously opened, but it had been disturbed throughout at some distant period, and no trace of the deposit could be found, although the yellow sand forming the subtratum was noticeable, calcined over the whole area as before. There were also traces of charcoal. It is remarkable that amidst the smaller stones of this cairn another ‘ rubbing stone ‘ was found, almost identical with that in the former one, and similarly, this proved to be the only ‘ find ‘ of any description bearing certain traces of man’s handiwork.

“Although somewhat disappointing not to be able to assign the erection of these cairns to any definite period, yet their examination proves valuable for two reasons. First it places beyond any question the nature of the mounds scattered over this portion of Brimham Moor, which is known by the name of ‘ Graffa Plain,’ a name which the late Mr. William Grange translates as ‘ the place of graves ‘ — significant in itself, though he at the same time casts a doubt upon the formation of the mounds in question being anything other than natural. The identity of the grave mounds being established, they prove that a settlement of primitive man of no small magnitude must have been located somewhere in the vicinity.”

The word ‘graffa’ seems to be the plural for ‘graff’, which the english dialect magus, Joseph Wright (1900), convincingly assures us to derive from the old english, “græf, a grave, trench.” This seems confirmed by the common finding of ‘graff’ in regional dialects from Yorkshire, Lancashire and other northern counties, where it relates specifically to ‘graves.’ A variation on the word, as cited above, finds ‘graff’ occasionally relating to “a ditch or trench; a channel, cutting; a hole, pit or hollow.” The usually helpful A.H. Smith (1961-63) was curiously silent on this place-name; but local historians Grainge, Walbran and others tell us that Graffa Plain is simply “the plain of the graves.”

I know of no other accounts that have explored this site. Does anyone have any further information about this place?

References:

- Armstrong, A. Leslie, “Two Ancient Burial Cairns on Brimham Moor, Yorkshire,” in The Naturalist, March 1909.

- Hargrove, Ely, The History of the Castle, Town and Forest of Knaresborough, Hargrove & Sons: Knaresborough 1809.

- Smith, William, “Yorkshire Place-Names,” in W. Smith’s Old Yorkshire – volume 1 (Longmans, Green & Co.: London 1881).

- Wright, Joseph (ed.), English Dialect Dictionary – volume 2, Henry Frowde: London 1900.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian