Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – NT 6504 2045

Archaeology & History

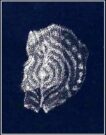

A little-known cup-and-ring stone that was uncovered in the forecourt of Jedburgh Abbey by Walter Laidlow in 1903, now lies all but forgotten in the abbey grounds. Laidlow’s original description of his find was very basic indeed: “a sculptured stone, with incised ring-and cup-symbols… of yellow sandstone, 1 foot 8 inches long, 9½ inches broad, 4 inches thick.” The Royal Commission (1956) lads did slightly better, saying:

“A slab of stone… measures 1ft 8½in by 9½in by 4in, and bears on one face six cup-marks ranging from 1in to 2½in in diameter. The largest of these is encircled by a ring 5in in diameter, in “pocked” technique; while slight traces of what may have been a similar ring can be seen around another cup, which is fractured.”

You can see from the photograph how the stone has been broken from a larger piece, strongly suggestive of a greater prehistoric design on the original slab—but there have been no subsequent finds that might show us its original form. In all likelihood, the stone originally came from a prehistoric tomb, but we know not where that might have been—much like the Mathewson’s Garden carving, also in Jedburgh.

The carving apparently still lies somewhere in the Abbey grounds, sleeping, but I’ve not visited the olde stone so I don’t know its exact position. If any local folk can tell us more, that would be great!

References:

- Laidlaw, Walter, “Sculptured and Inscribed Stones in Jedburgh and Vicinity,” in Proceedings Society Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 39, 1905.

- Morris, Ronald W.B., “The Cup-and-Ring Marks and Similar Sculptures of South-West Scotland,” in Transactions of the Ancient Monuments Society, volume 14, 1967.

- Morris, Ronald W.B., “The cup-and-ring marks and similar sculptures of Scotland: a survey of the southern Counties – part 2,” in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 100, 1969.

- Morris, Ronald W.B., The Prehistoric Rock Art of Southern Scotland, BAR: Oxford 1981.

- Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments of Scotland, Roxburghshire – volume 1, HMSO: Edinburgh 1956.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian