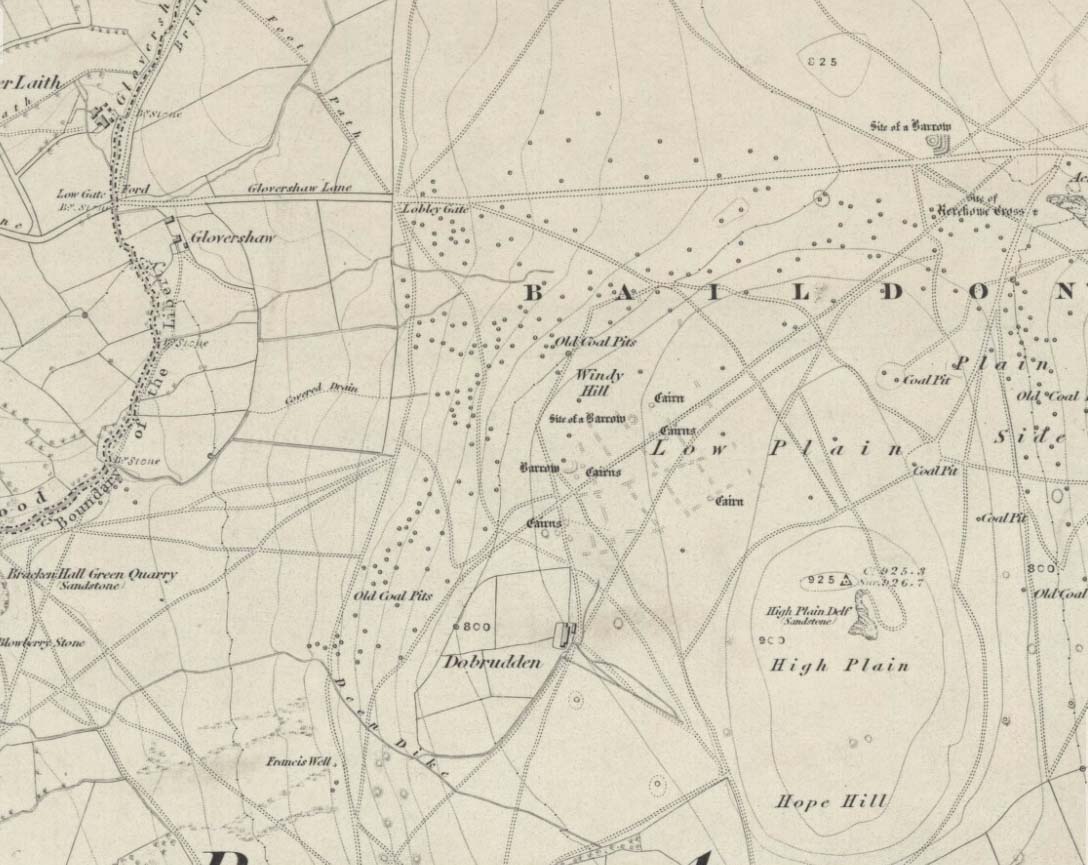

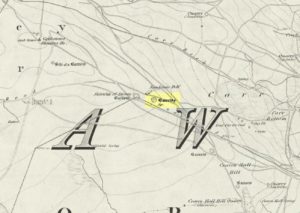

Ring Cairn: OS Grid Reference – SE 1770 5136

From the Askwith Moor Road parking spot, walk up the road for about 500 yards and head to your right (east) onto the moor. Walk past the upper side of the disused quarry and through the heather for about 200 yards until the moorland slopes down and you’re on another flat moorland ridge. You should now be stood on the edge of the Snowden Crags Necropolis or cairnfield. There’s a large patch of bracken near the top of Snowden Crags in the middle of the prehistoric cemetery. That’s the spot!

Archaeology & History

Very little has been written of this site and for years several of us have wondered whether or not a stone circle was the antiquity that was being described in the only singular reference of the place, mentioned almost in passing in Mr Cowling’s (1946) fine survey of this area more than fifty years back, where he reported:

“A large circle of heavy material, some thirty feet in diameter, is isolated on the shelf above Snowden Crags to the west.”

But despite the various explorations of me and a number of other students on these moors over the last 20-30 years, Cowling’s curious singular reference (which some have taken as an error of judgement on his behalf) has remained a mystery. Until now!

Thankfully, with the help and attention of the hardworking Keighley volunteer Michala Potts on Thursday, 20 May, 2010, this large and very well-defined antiquity has been relocated — and a damn fine find it is indeed! It would appear (unless someone has notes to the contrary) that when Cowling did his extensive walkabouts on these and adjacent moors, this Snowden Crags Circle was much overgrown in heather and bracken; and I think we can safely assume this due to him making no further remarks regarding the site. Indeed, it would seem that Cowling’s consequent silence on the matter would lend us to think he never caught good sight of this “large circle” ever again. And upon these moors, that’s easily done when the heather gets deep up here! (numerous cup-and-ring stones on these and other northern moors still lay hidden amidst moorland undergrowth, awaiting rediscovery as a consequence of the deep vegetation) But thankfully now we have a good view of the place.

Wrongly ascribed by Neil Redfern of English Heritage to be a part of Scheduled Monument Record number 28065: Cairnfield, Enclosures, Boulder Walling, Hollow Way and Carved Rocks (it’s actually a short distance north of SMR 28065), the site here was relocated during one of The Northern Antiquarian exploratory walks, assessing the extensive walling, settlement pattern and prehistoric graveyard that scatters the central and northwestern section of the moors here. Michala Potts stopped and shouted for Dave Hazell and I to come and have a look at something she’d found whilst we were carefully peeling turf back from a previously unrecorded site about 100 yards away.

“What is it?” I asked; expecting just another small tomb or new cup-and-ring stone. But her tone of voice was different this time.

“I think you’d better take a look at this,” she emphasized.

As we walked through the shallow heather towards her, it became obvious she was standing in a rough circle of dead bracken, unbroken by the lack of rain over the previous months. We’d actually walked past it a couple of times the previous week and gave it no attention due to the depth of the dead vegetation covering the area. But this time it was different. I got within 50 yards of where Mikki was stood and my footsteps slowed; a couple more steps perhaps; then I stopped dead in my track. My arms lifted up and I held my head gazing at what she appeared to be stood in.

“Aww my god….” I said — transfixed at what was in front of me (I’m easily pleased aswell!).

I’m not quite sure how long I stood there with my head in my hands. Ten seconds or so. I couldn’t really say. I think it was when Dave caught up to where I stood, rooted, and appeared at my side. We walked a bit closer to make sure that what we could see wasn’t just another one of those curious shapes in the landscape that you find when seeking out prehistoric sites and turn out to be bugger all — but it wasn’t. Instead, Mikki Potts had stumbled upon an average-sized ring of stones, between 1-3 feet tall, and about 13 yards across, with what seemed like an entrance on its southern side, seemingly untouched in the middle of the mass of decaying bracken! It was an exciting find — as it’s not everyday that you come across a previously unrecorded stone circle. But, once we’d calmed down and walked round and round the site to make sure that something man-made was under our feet, we decided to make our way home (we’d been on the moors all day) and get back up to have a more detailed look at the place in a few days time. On Tuesday, May 25, we went back up for a second time and had a better look at the place…

It was another lucky day. For before we even reached Askwith Moor, Mikki pointed out what looked like a small cup-marking on a stone yards from the edge of the River Wharfe. We brushed off a bit of the dusty earth and were greeted the single cup-marked stone we’ve named the Riverbank Stone. It sat there all alone and dusty and we were very tempted to look for more potential carvings along the riverbank, but the Snowden Crags site was calling for attention and so up the hill we walked.

The ring of stones was still covered in a carpet of dead bracken and also had the new shoots of Spring emerging from the Earth, so we spent the next few hours picking up much of the dead bracken and carrying it beyond the outskirts of the circle, hence enabling us to see with greater clarity the monument Mikki had found a few days previously. The hot sun shone down on us all day and it took longer than we expected to shift all the bracken; but eventually, once we’d done it, we were looking at a very distinct man-made circular monument, measuring 13 yards by 12 yards across and, at its highest point, not even three feet above the present ground level. But today’s ground level is certainly much higher than it was when these stones were first placed here — at least 12 inches higher.

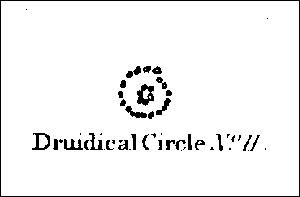

When Mikki first clapped eyes on the place, only a few small upright stones were sticking up amidst the mass of compacted bracken, but once all this had been brushed off we could see the stony earthworks averaging 18 inches high around the edges; and in places this outer ring is nearly 6 feet across. The ring consists mainly of smaller packing stones (perhaps thousands of them) between a number of larger upright stones — a dozen of them — making up the perimeter; but much of this perimeter is still considerably overgrown in compacted vegetation that’s prevented us seeing the ring in its proper glory: what archaeologists in the past have called a rubble bank. On its southern side is what appears to be an entrance, i.e., in this part of the circle there are no larger stones at all and only a handful of small stones have been noticed; but we must take into account the fact that we’ve done no excavation work here and this “entrance” may in fact be illusory, as the centuries of compacted vegetation (in all probability at least 12 inches deep) could be overlaying an unseen portion of the ring. This “entrance” is about 2 yards across.

The circle has similarities in size and design to the better-known site of Roms Law on Ilkley Moor. The difference between the two however is Roms Law has been robbed, whilst the Snowden Crags circle hasn’t even been catalogued. Yet there is a distinct anomaly here.

As we walked through the southern “entrance” and into the circle, we noticed what seemed to be some form of internal walling running roughly north-to-south. This “walling” started about three yards between the southern “entrance” and the inside of the ring, but then it ran roughly through the centre and all the way to the northern perimeter. This was indicated by a distinct rise in the ground which, as you walked over and stomped your feet, proved to be a mass of numerous small stones seemingly a few inches under the ground, some of which were poking through the Earth’s surface. This ingredient alone made me stop and wonder about the nature of the site. Had we come across a cairn circle of some sort? Or were we in fact stood in the middle of a small walled enclosure, which itself sits in the middle of this prehistoric graveyard? Indeed, was this walled enclosure a potential living quarter: some sort of large hut circle with a wall through the centre splitting it in two? It was hard to say for sure. On another visit to this site a couple of weeks later, in the company of Geoff Watson, Paul Hornby and Dave Hazell, this potential internal walling was given a bit more scrutiny.

We were dying to get our hands and feet digging at the heart of this ring of stones but — as yet! — we’ve managed to restrain ourselves. Although carrying off the mass of dead bracken has dislodged a couple of the small fist-sized stones at the edge of the ring (we carefully placed ’em back into position; yet it was only as much as you’d unintentionally disturb if you walked over the place a few times), we needed to use a couple of small brushes to have a look at this apparent internal walling running through the middle of the ring. But after carefully brushing off the dry dead earth, we found this “walling” was nothing of the sort! Instead, it seemed, someone at some time in the past had beaten us to this place! The central walling was, in fact, where someone had dug into the central region of the circle — probably looking for treasure or other wealthy valuables — and in doing so had dislodged a great number of the small stones that were initially in the middle of the ring, and in doing so pushed them up into small piles of stones, away from their original central position, creating an obvious long line of rocks which, once covered with dead vegetation, gave the impression of it being a length of walling. We also found that the mass of rocks that were around the centre of the ring also spread outwards covering all of the ground inside the outer kerb of stones — probably thousands of them. Geoff called this trench in the middle, the Robber’s Trench!

This begged the question: who the hell had been here, dug out a trench in the middle of this cairn circle (possibly taking out whatever remains were in the middle) centuries before the site had even been catalogued? It didn’t seem like it could have been Mr Cowling, as the covering vegetation was much more than a mere 50 years of age; and Cowling would very likely have reported any finds that he might have made here. So it is a mystery that needs solving.* Again, an accurate archaeological excavation would be invaluable here — but I wouldn’t hold your breath. Archaeological officials don’t seem interested in helping here. I was informed by Neil Redfern of the archaeology department of English Heritage for North Yorkshire that they are unable to support any funding that might help towards any decent analysis of this important archaeological arena (probably spent all their cash on prawn sandwiches and tedious autocrats, as usual).

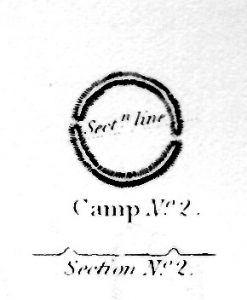

So what we have so far is this: a large flattened circle consisting of at least a dozen upright stones that define the edges. Between these uprights are hundreds, perhaps thousands of smaller stones, making a rubble bank of a near unbroken circle, apart from where there seems a small entrance on its southern side. Inside the circle is a scattered mass of many small stones, typical of cairn material, filling the entirety of the monument; but the central region has been dug into at some time in the past, by persons unknown. It sits on a flat plain of moorland amidst the Snowden Crags Necropolis with around 30 other small cairns. But this particular site is several times larger than all the others, probably indicating that whoever was buried/cremated here was of some considerable importance in the tribal group: a local king, queen, tribal elder or shaman. Whoever it was that this monument was made for, the landscape reaching northwards from here looks across to the giant morphic temples of Brimham Rocks and the heavenly landscape beyond and above them. It is very likely that the Lands of the Ancestors this way beckoned…

References:

- Cowling, Eric T., Rombald’s Way: A Prehistory of mid-Wharfedale, William Walker: Otley 1946.

LINKS:

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Huge thanks for the help, assistance and photographs of this newly discovered site — and others nearby — to Michala Potts, Dave Hazell, Paul Hornby and Geoff Watson.

* There is a legend that tells of gold and treasure found at a nearby pre-christian well, but this site is a mile to the north of here. Another nearby treasure legend is that of a chap called “Robinson”, who came upon tons of wealth from an unknown source, enabling him to build the eloquent Swinsty Hall a mile northwest of here (though such a chap didn’t actually build Swinsty!). Perhaps there’s some grain of truth somewhere down the line about someone finding some treasure hereby…perhaps here…perhaps not!

AN APPEAL TO SOME DECENT RICH CHAP FOR SOME MONEY TO ENABLE EXCAVATION HERE!

This site and the surrounding monuments have received no archaeological attention of any worth. If it wasn’t for the fact that us amateurs had explored these (and adjacent) moors, this cairn circle would remain unknown, many of the cup-and-rings upon these moors would remain unknown, the extensive enclosures and walling (of indeterminate age and function) would remain unknown, many prehistoric tombs would remain unknown, etc. It is clearly evident that we have quite extensive domestic and ritual remains covering this small moorland region, from the neolithic period onwards. In the event that anyone reading this with a healthy financial backing behind them could work out a financial strategy enabling us to accurately excavate this and the adjacent monuments, please get in touch. We need an archaeologist to be paid for in order that we can do the duties correctly, but there is a group of a dozen volunteers willing to put a lotta work in to do the right job in this and the surrounding sites. Is there anyone out there who has the finance to enable this? I’m serious! Or are these important sites merely going to be left alone for the elements to consume and disappear over time? Surely there are one or two rich antiquarians left in this country who, as in times of old, are willing to help in the investigation of our country’s ancient monuments? Does anyone out there know how we can get the ball rolling?

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian