Standing Stone: OS Grid Reference – NR 83865 93619

Also Known as:

- AR27 (Ruggles 1984)

- Canmore ID 39592

From Lochgilphead, take the A816 road north for several miles (towards the megalithic paradise of Kilmartin), keeping your eyes peeled for the road-signs saying “Dunadd.” Turn left and park-up. Instead of walking up the craggy fortress, follow the road-track to the house and, alongside the River Add, you’ll see the standing stone in the well-mown garden on your right.

Archaeology & History

As a monolith within the Kilmartin Valley complex, this is a slight, almost gentle standing stone, missed by most when they visit the other larger sites in Argyll’s Valley of the Kings. Set upright close to the gentle winding River Add and only a few yards from the ancient ford that bridged the waters beneath the shadow of Dunadd’s regal fortress, the late great Alexander Thom (1971) wrote about it in his exploration of lunar alignments found at other nearby standing stones. This one however, was 3° out to have any astronomical validity.

Described only in passing by a number of writers, the greatest literary attention it has previously been afforded was by the Royal Commission lads (1988), whose notes on it were short:

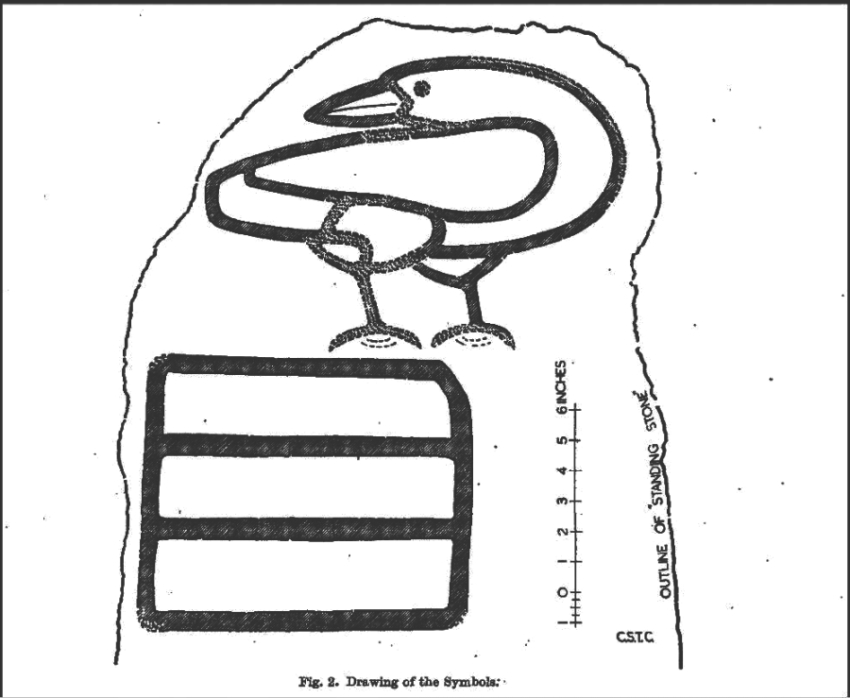

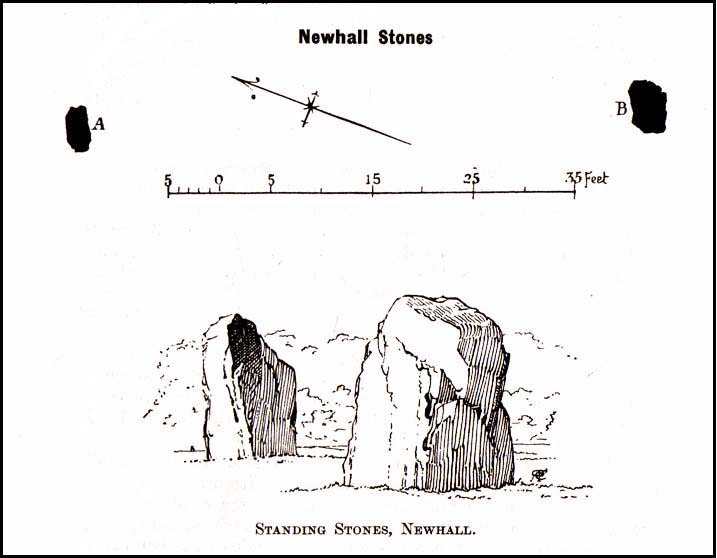

“An irregularly-shaped block of stone, 1.35m high and 1.35m in girth at the base, is situated 25m S of Dunadd farmhouse, it is aligned NNW and SSE, and the top the SSE edge appear to have been broken off.”

…My first visit here was when I lived north of Kilmartin and each time I found the same ‘gentle’ feeling, in all different weathers: a most unusual phenomenon, as there tends to be changes in psychological states between rain, sunshine, frosts, dark night and mists. But there was a consistency of subtlety; a regularity in genius loci—probably due to its proximity to the River Add, the lowland tranquility below the crags. It’s a wonderful little place. Well worth visiting if you go to Dunadd.

References:

- Campbell, Marion, Mid-Argyll: An Archaeological Guide, Dolphin Press: Glenrothes 1984.

- Lane, Alan & Campbell, Ewan, Dunadd: An Early Dalriadic Capital, Oxbow: Oxford 2000.

- Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments of Scotland, Argyll – Volume 6: Mid-Argyll and Cowal, HMSO: Edinburgh 1988.

- Ruggles, Clive L.N., “A critical examination of the megalithic lunar observatories,” in Ruggles & Whittle, Astronomy and Society in Britain, BAR: Oxford 1981.

- Ruggles, Clive L.N., Megalithic Astronomy, BAR: Oxford 1984.

- Thom, Alexander, Megalithic Lunar Observatories, Clarendon: Oxford 1971.

- Thom, A., Thom, A.S. & Burl, Aubrey, Stone Rows and Standing Stones – volume 1, BAR: Oxford 1990.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.