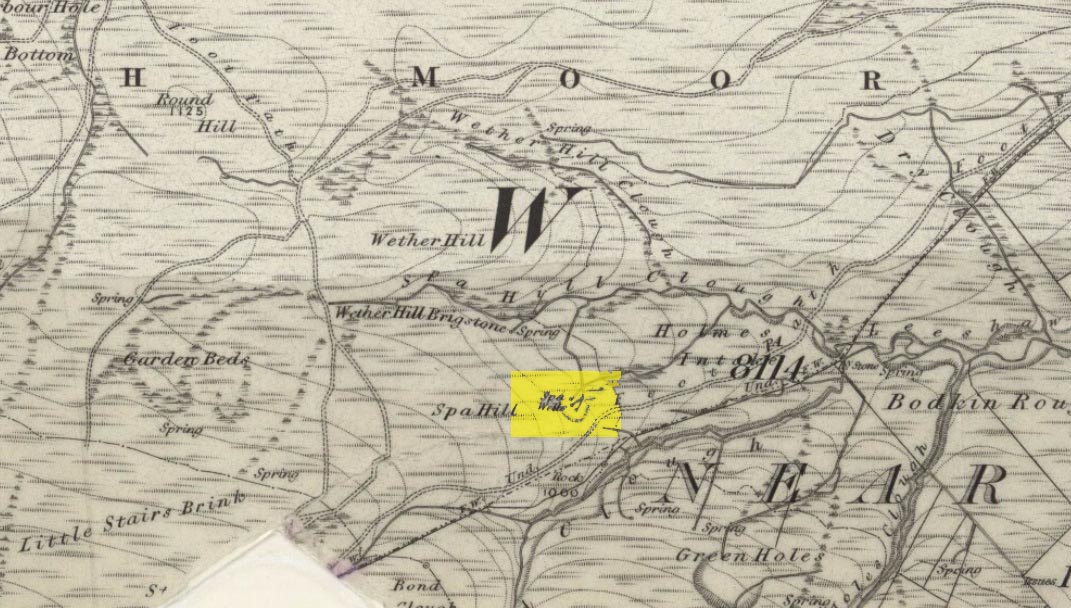

Holy Well: OS Grid Reference – NT 24401 74070

Also Known as:

In Edinburgh, get to the west-end of Princes Street (nearest the castle), and where there’s the curious mess of 6 roads nearly skewing into each other, head down Queensferry Street for 450 yards until, just before you go over the bridge, walk down Bells Brae on your left, then turn right down Miller Row where you’ll see the sign to St. Bernard’s Well. St. George’s Well is the small, dilapidated spray-painted building right at the water’s edge 200 yards before St. Bernard’s site.

Archaeology & History

Compared to its companion holy well 200 yards downstream, poor old St. George’s Well is a paltry by comparison, in both historical and literary senses. The site was said to have been “set up in competition with St Bernard’s Well but never achieving its purpose”, wrote Ruth & Frank Morris (1982)—which is more than a little sad. Not on the fact that it failed, but on the fact that some halfwits were using local people’s water supply to make money out of and, when failing, locked up the medicinal spring and deny access to people to this day!

In Mr Grant’s Old & New Edinburgh (1882), the following short narrative was given of the site:

“A plain little circular building was erected in 1810 over (this) spring that existed a little to the westwards of St. Bernard’s, by Mr MacDonald of Stockbridge, who named it St. George Well. The water is said to be the same as the former, but if so, no use has been made of it for many years…”

The association to St. George was in fact to commemorate the jubilee of King George III that year. If you visit the place, the run-down little building with its grafitti-door has a small stone engraving etched above it with the date ‘1810’ carved.

As the waters here were found to possess mainly iron, then smaller quantities of sulphur, magnesia and salts, it was designated as a chalybeate well. Its curative properties would be very similar to that of St. Bernard’s Well, which were very good at,

“assisting digestion in the stomach and first passages … cleansing the glandular system, and carrying their noxious contents by their respective emunctories out of the habit, without pain or fatigue; on the contrary, the patient feels himself lightsome and cheerful, and by degrees an increase to his general health, strength and spirits. The waters of St. Bernard’s Well operates for the most part as a strong diuretic. If drunk in a large quantity it becomes gently laxative, and powerfully promotes insensible perspiration. It likewise has a wonderfully exhilarating influence on the faculties of the mind.”

References:

- Bennett, Paul, Ancient and Holy Wells of Edinburgh, TNA: Alva 2017.

- Grant, James, Cassell’s Old and New Edinburgh – volume 3, Cassell, Petter Galpin: London 1882.

- Harris, Stuart, The Place-Names of Edinburgh, Gordon Wright: Edinburgh 1996.

- Hill, Cumberland, Historic Memorials and Reminiscences of Stockbridge, the Dean and Water of Leith, Robert Somerville: Edinburgh 1887.

- MacKinlay, James M., Folklore of Scottish Lochs and Springs, William Hodge: Glasgow 1893.

- Morris, Ruth & Frank, Scottish Healing Wells, Alethea: Sandy 1982.

- Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments, Scotland, Inventory of the Ancient & Historical Monuments of the City of Edinburgh, HMSO: Edinburgh 1951.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.