Legendary Rock: OS Grid Reference – SE 03399 30199

Also Known as:

- Sleepy Lowe

From Denholme, take the A6033 Hebden Bridge road up, but shortly past the great bend turn off right up the steep road towards the moorland windmills until you reach the flat dirt-tracked road, past the reservoir below. A coupla hundred yards past the track to the reservoir, take the footpath south into the tribbly grasslands and moor. A few hundred yards down you’ll note the large rock outcrop ahead of you. The rocking stone is there!

Archaeology & History

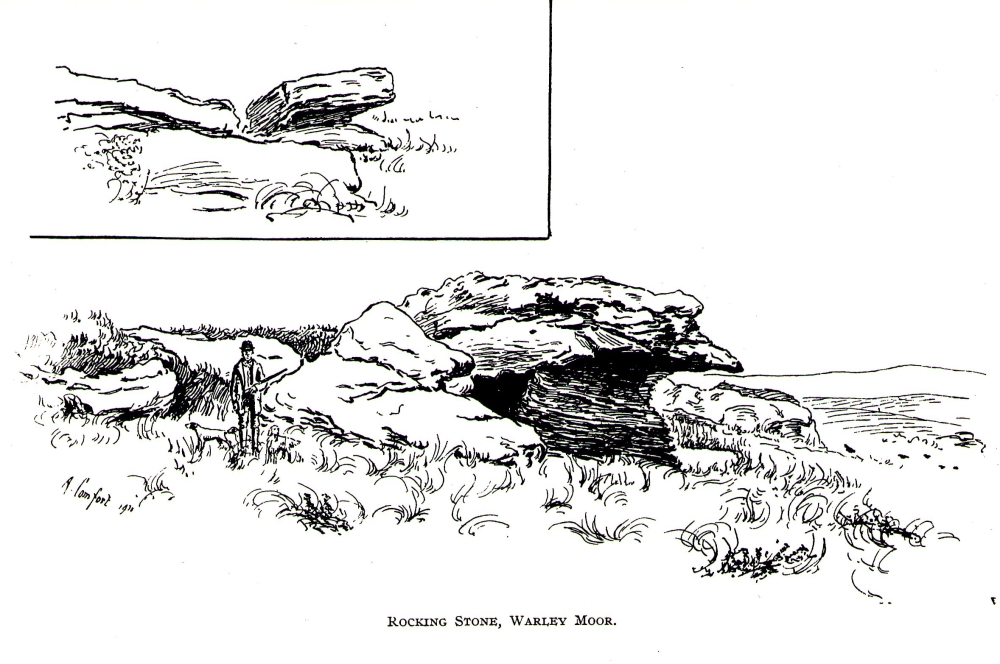

A small moorland arena with a neglected history. Many lost memories surround this site, with barely legible ruins from medieval and Victorian periods prevailing against scanty snippets of neolithic and Bronze Age rumours and remains. The rocking stone here—which moves slightly with a bit of effort—sits amidst a gathering of other large rocks, some of which have debatable cup-markings on their smoothly eroded surfaces.

Our rocking stone, resting 1350 feet (411m) above seal level, was first mentioned in John Watson’s (1775) magnum opus, who gave a quite lengthy description of the site, telling us that,

“On a common called Saltonstall-moor, is what the country people call the Rocking-stone… The height of this on the west side (which is the highest) is, as I remember, about three yards and a half. It is a large piece of rock, one end of which rests on several stones, between two of which is a pebble of a different grit, seemingly put there for a support, and so placed that it could not possibly be taken out without breaking, or removing the rocks, so that in all probability they have been laid together by art. It ought to be observed, that the stone in question, from the form and position of it, could never be a rocking stone, though it is always distinguished by that name. The true rocking stone appeared to me to lie a small distance from it, thrown off its centre. The other part of this stone is laid upon a kind of pedestal, broad at the bottom, but narrow in the middle; and round this pedestal is a passage which, from every appearance, seems to have been formed by art, but for what purpose is the question.”

Watson then goes onto remark about other rocking stones in Cornwall and further afield with attendant “druid basins” on them, noting that there were also “rock basins” found here on Warley Moor, a few of which had been “worked into this rocking stone,” which he thought, “helps to prove that the Druids used it.” And although these rock basins are large and numerous over several of the rocks on this plateau, like the cup-markings that also scatter the surfaces, they would seem to be Nature’s handiwork.

Some 60 years later when the literary thief John Crabtree (1836) plagiarized Watson’s words verbatim into his much lesser tome, it seemed obvious he’d never ventured to explore the site. But in the much more valuable historical expansion written by John Leyland around 1867, he at least visited the site and found the old stone, “still resting on its shady pedestal.” Later still, when Whiteley Turner (1913) ventured this way on one of his moorland bimbles, he added nothing more to the mythic history of these west-facing megaliths…

Folklore

Still reputed locally to have been a site used by the druids; a local newspaper account in the 1970s also told how local people thought this place to be “haunted by goblins.”

References:

- Bennett, Paul, The Old Stones of Elmet, Capall Bann: Milverton 2001.

- Crabtree, John, Concise History of the Parish and Vicarage of Halifax, Hartley & Walker: Halifax 1836.

- Leyland, F.A., The History and Antiquities of the Parish of Halifax, by the Reverend John Watson, M.A., R.Leyland: Halifax n.d. (c.1867).

- Smith, A.H., The Place-Names of the West Riding of Yorkshire – volume 3, Cambridge University Press 1961.

- Turner, Whiteley, A Spring-Time Saunter round and about Bronte Lane, Halifax Courier 1913.

- Watson, John, The History and Antiquities of the Parish of Halifax, T. Lowndes: London 1775.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.