Settlement: OS Grid Reference – NC 5764 6248

Getting Here

Large arc of low walling, across upper-centre

Along the A836 road between Durness and Tongue, take the minor road north to Melness and Talmine. 400 yards or so past Talmine Stores shop, walk left up the track onto the moor. Half a mile on, walk straight uphill on yer right for about 150 yards until it levels out. Look all around you!

Archaeology & History

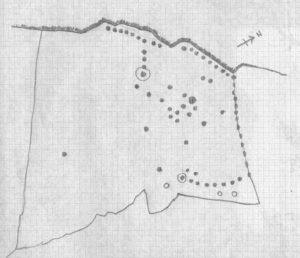

This is a fascinating new find, explored under the guidance of Sarah MacLean of Borgie. After looking at the nearby cairnfield and hut circles to the southeast, our noses took us onto the hilltop, where an extravaganza of curved and straight walling, hut circles, denuded cairns, cists, possible chambered cairn remnants and even unrecorded stone rows had us almost bemused at the extent of the remains. A lot of it has been severely damaged and robbed – but in the low vegetation scattering the hilltop, it became clear that a lot of activity had been going on in the ancient and perhaps not-too-ancient past, with a social and/or tribal continuity stretching way way back (as found at Baile Mhargaite near Bettyhill).

Straight line of low walling

As we walked up the unnamed hill (well, to be honest, we zigged and zagged, or bimbled, until we got to the top), above a line of prehistoric cairns on the slopes below, small lines of walling barely above ground-level stretched out before us. Structurally akin to the neolithic and Bronze Age features found from northern England to this far northern region, they are low and deeply embedded in the peat, but are quite unmistakable.

In following the first real line of walling near the eastern edge of the hill, a flat panorama eventually opened up as we reached the top and there, in front of us, appeared arcs and lines of more walled structures, thankfully unobstructed by vegetation. A few expletives came out of my mouth (for a change!) at the remains we could see right in front of us—and then we set walking in different directions and began to explore the remains beneath our respective feet.

The first main element on the southeastern top of the hill was a wide curvaceous arc of walling, undoubtedly prehistoric – in my opinion either Bronze Age or neolithic in origin. As I was looking at this section, Sarah walked only a short distance to the northwest and, with some excitement in her tone called out, “there’s some here too!” And so we continued, back and forth to each other as we zigzagged across the tops.

Stone row or denuded walling?

Intersecting lines of walling

Much of what we found (as the photos show) were low lines of settlement walling—some dead straight, others curving to form denuded hut circles and larger domestic forms. A lot of the walls had been knocked down and scattered on the hilltop, making it troublesome at times ascertaining precisely what we were looking at: but a settlement or large enclosure it certainly is!

The south and western edges of the hill itself seemed to be marked by low sections of walling, again deeply embedded into the peat; and on the same two sides are what appear to be remnants of stone rows leading up onto the top. As with other stone rows in this region, they are defined by low upright monoliths. The one that runs north-south runs into a low section of walling that cuts right across the top of the hill and away into the deep peat, roughly NNE, where we lost sight of it (where some old peat-cutting is evident). The stone row running up the western face of the hill seems to begin near the bottom of the slope and is defined by a leaning standing stone that Sarah found. Looking uphill from this there’s a gap of roughly fifty yards, where a small stone sits on the near-horizon; and from this small stone is a clear line of small stones, ending (it seems) at a stone less than three feet tall. Just past this is the denuded remains of what seems to be a cist and a small robbed cairn, clearly defined by a curious rectangle of base-stones, barely 5 feet by 3 feet wide.

Intersecting arc & line of walling

Outline of robbed cairn?

My personal favourite of all the things on top of this hill has to be the small sections of interconnecting walling that we found on the more northern portion of the settlement. At first glance, it seemed that we were just looking at a small hut circle; but then we realised this initial ‘hut circle’ was linked to a slightly larger ‘hut circle’, which was linked to another, all in a linear east-west direction (roughly). As I saw looked at it from the western-side (looking east), Sarah was on its east looking west. This difference in visual perspective gave us a wider view of what we were both looking at. The easternmost section comprised of an arc of walling that joined into another ‘hut circle’, neither of which had axes any greater than 3 yards. As we stepped further and further back from this, it seemed that other walled sections ran into it, expanding it into a form which I can only describe as a ‘stripped long cairn’, down to its initial architectural basis, upon which you’d construct the larger monument—but it was only 10 yards long at the most. Most odd… Sarah pointed out what may have been a stoned-lined trackway running parallel to this neolithic curiosum. It still puzzles me as to what it may have been.

This short description doesn’t really do this site justice and, in truth, it needs a more competent survey than I could give it in just one short visit. It’s very probable that a lot more is still to be found on these hills, from prehistoric all through to post-medieval (pre-Clearance) times. So if you live in this part of Sutherland, get yer twitching noses and boots on and bimble with intent to find! There’s still plenty of stuff hiding away…

Acknowledgements: Huge thanks to Donna Murray of Borgie for putting me up (or should that be, putting up with me?!) and equally massive thanks to Sarah Maclean—also of Borgie—for guiding me up here and being an integral part of rediscovering this site. Without them both, this place would still be unrecognised. And thanks to Miles Newman too.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.