Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – SE 12961 46396

Also known as:

- Carving No.137 (Hedges)

- Carving No.295 (Boughey & Vickerman)

- Planet Stone

- The Planets Rock

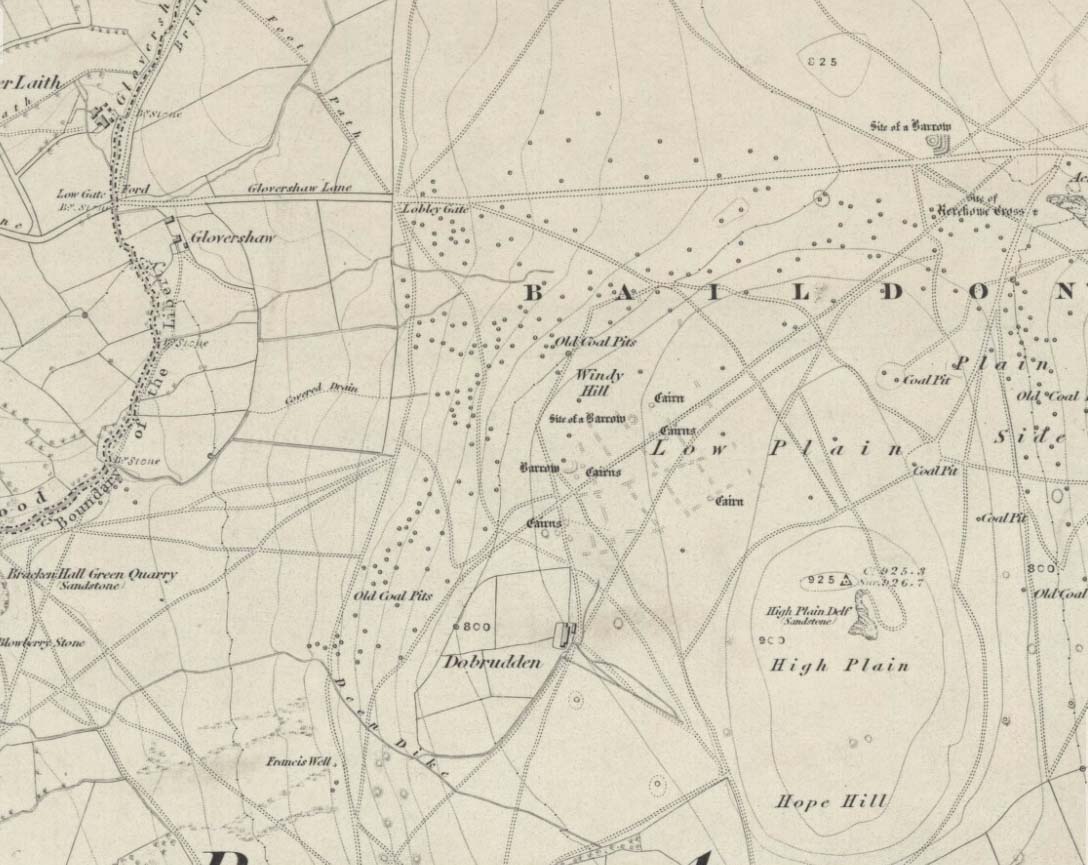

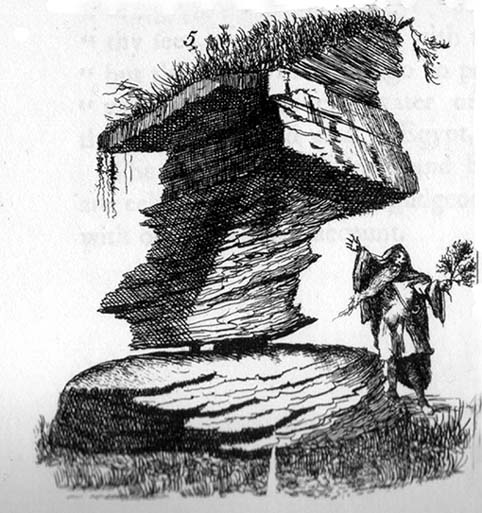

Best visited in winter and spring – thereafter the vegetation can hide it a little – but even then, it’s not too hard to find. Start from the Cow & Calf Hotel and walk across the road onto the moor, and head over as if you’re gonna walk above the Cow & Calf Rocks, onto the moorland proper. When you’ve gone a few hundred yards, walk up the slope (there are several footpaths – you can take your choice). Once on the ridge on top of the moor proper, you’ll see the Haystack Rock: it’s on the same ridge, right near where the moor drops down the slope about 250 yards west of here, just about next to the footpath that runs along the edge. Look around!

Archaeology & History

Unlike some folk who’ve seen this old stone, I find this carving superb. Its one of my favourites up here! Its alternative name – the Planet Stone – perhaps lends you to expect something more, but this is down to the astronomer who thought this was some type of heavenly image (which is most unlikely). I prefer to call it the ‘Map Stone’ because the correlates this carving has with indigenous aboriginal cup-and-rings is impressive and — to Aborigines anyway — would have all the hallmarks of a map. But not a ‘map’ in the traditional sense of modern humans. The incidence of cups and rings linked by curvaceous lines, typifies routes between water-holes or settlement spots made by ancestral beings — which is just what we find at this carving here. These ancestral beings need to be seen in a quite mythic sense: they may be creation deities (giants, gods, etc), animal spirits, the routes of shaman spirits, or other expressions of homo-religiosus.

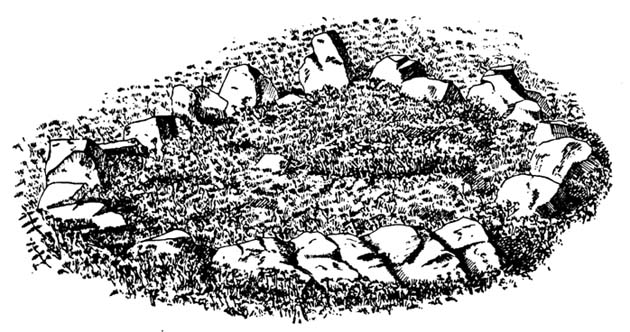

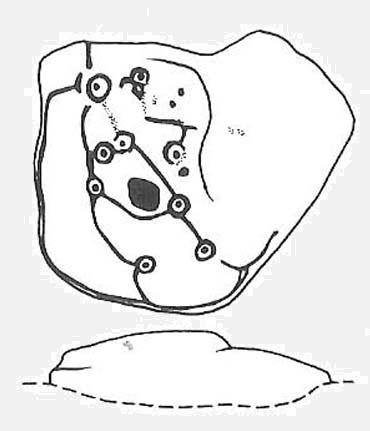

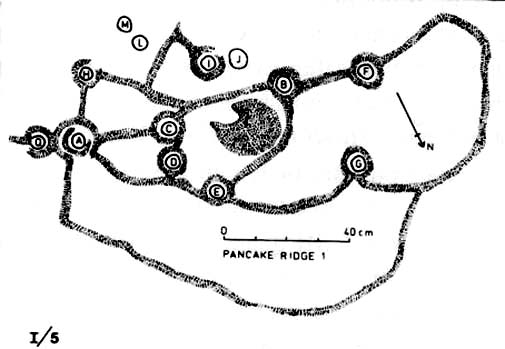

In the Map Stone here, we see that the very edge of the rock (fig.2 & 3) is ‘encircled’, perhaps (and I say perhaps) symbolic of the edge of the world. The lines and rings upon the top of the rock may symbolize journeys to and from important places. Another impression I get of this carving, with the “map” idea, is that the large pecked diamond-shaped ‘cup’ near the middle of the carving is a large body of water around which the archaic routeways passed. The next time anyone visits this stone, have a look at it with this idea in mind. Its simple, straightforward and makes sense (mind you – that doesn’t mean to say it’s right!).

The first account I’ve found of this comes from the pen of J. Romilly Allen (1882), where this stone “measuring 5ft 3in by 5ft, and 1ft 9in high” was described thus:

“On its upper surface, which is nearly horizontal, are carved thirteen cups, varying in diameter from 2 to 2½ in, eleven of which are surrounded by rings. There is also an elaborate arrangment of connecting grooves.”

Although we can only work our nine cup-and-rings here today, Mr Allen seemed suitably impressed with this old carving. Stan Beckensall (1999) seemed to have a good feel of this design too, describing it thus:

“Two thirds of the surface of this earthfast sandstone have been used in a design that partly encloses the marked part of the rock with long curvilinear grooves along its edge, and the inner grooves link single rings around cups. The effect is one of inter-connection and fluidity.”

The Map Stone was also looked at to examine the potential for Alexander Thom’s proposal of a megalithic inch: a unit of measure speculated to have been used in neolithic and Bronze Age times for the carving of cup-and-ring stones. Using nine other carvings on these moor as samples, Alan Davies (1983, 1988) explored this hypothesis and gave the idea his approval. However the selectivity of his data, not only in the carvings chosen, throws considerable doubt on the idea. Unfortunately the idea doesn’t hold water. The ‘geometry’ in the size of cup-and-rings relates more to the biometrics of the human hand and not early scientific geometry, sadly….

References:

- Allen, J.R., ‘Prehistoric Rock Sculptures of Ilkley,’ in Journal British Arch. Assoc., 35, 1879.

- Allen, J.R., ‘Notice of Sculptured Rocks near Ilkley, with some Remarks on Rocking Stones,’ in Journal British Arch. Assoc., 38, 1882.

- Allen, J.R., ‘Cup and Ring Sculptures on Ilkley Moor,’ in Reliquary Illus. Archaeology, 2, 1896.

- Beckensall, Stan, British Prehistoric Rock Art, Tempus: Stroud 1999.

- Boughey, K.J.S. & Vickerman, E.A., Prehistoric Rock Art of the West Riding, WYAS: Exeter 2003.

- Collyer, Robert & Turner, J.H., Ilkley: Ancient and Modern, William Walker: Otley 1885.

- Cowling, E.T., Rombald’s Way, William Walker: Otley 1946.

- Davis, Alan, ‘The Metrology of Cup & Ring Carvings near Ilkley in Yorkshire,’ Science Journal 25, 1983.

- Davies, Alan, ‘The Metrology of Cup and Ring Carvings,’ in Ruggles, C., Records in Stone, Cambridge 1988.

- Hedges, John, The Carved Rocks on Rombald’s Moor, WYMCC: Wakefield 1986.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian