Standing Stone: OS Grid Reference – NO 53647 52098

Also Known as:

- Canmore ID 34906

- Circle of Turin

- Fertility Stone

- Nether Turin

- UKIP Stone

- Wanker’s Stone

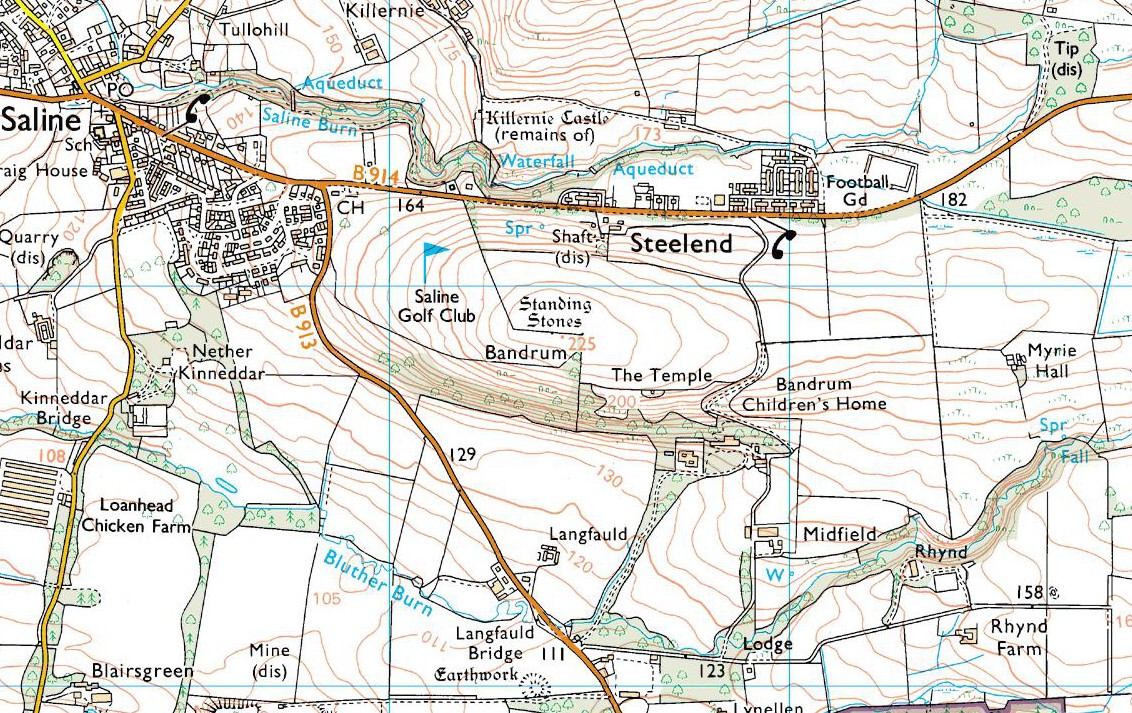

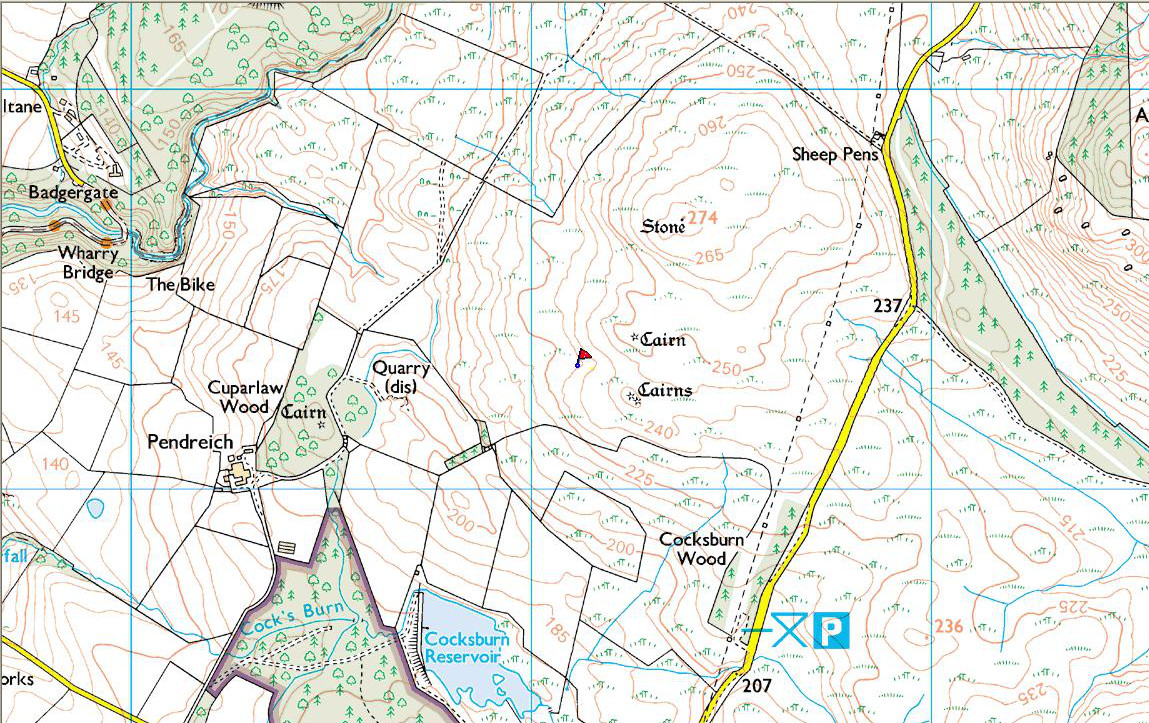

The easiest way to find this is by going along the B9113 road that runs from the east side of Forfar, out to Montreathmont Forest. Along this road, pass the Rescobie Loch and keep going for another mile or so, until you hit the small crossroads. Go left here as if you’re going to Aberlemno. Barely 100 yards up, opposite the newly-built Westerton house, the standing stone is on the rise in the field.

Archaeology & History

A truly fascinating heathen stone in a parish full of Pictish and early christian remains, with the faint remains of an intriguing carving that can still, thankfully, be discerned on the southwestern face of the upright….amongst other things…

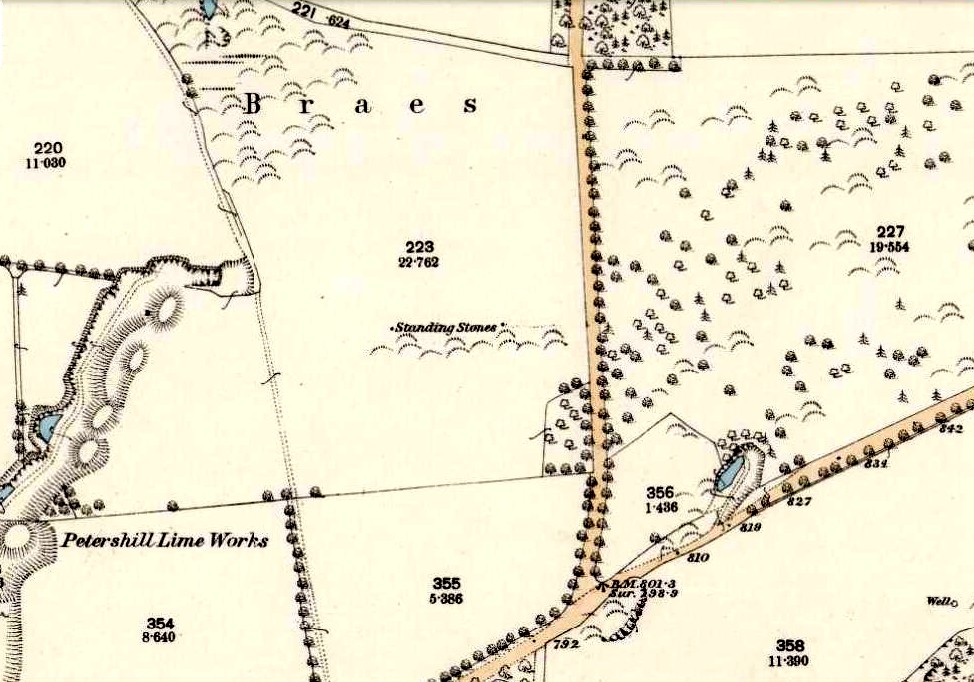

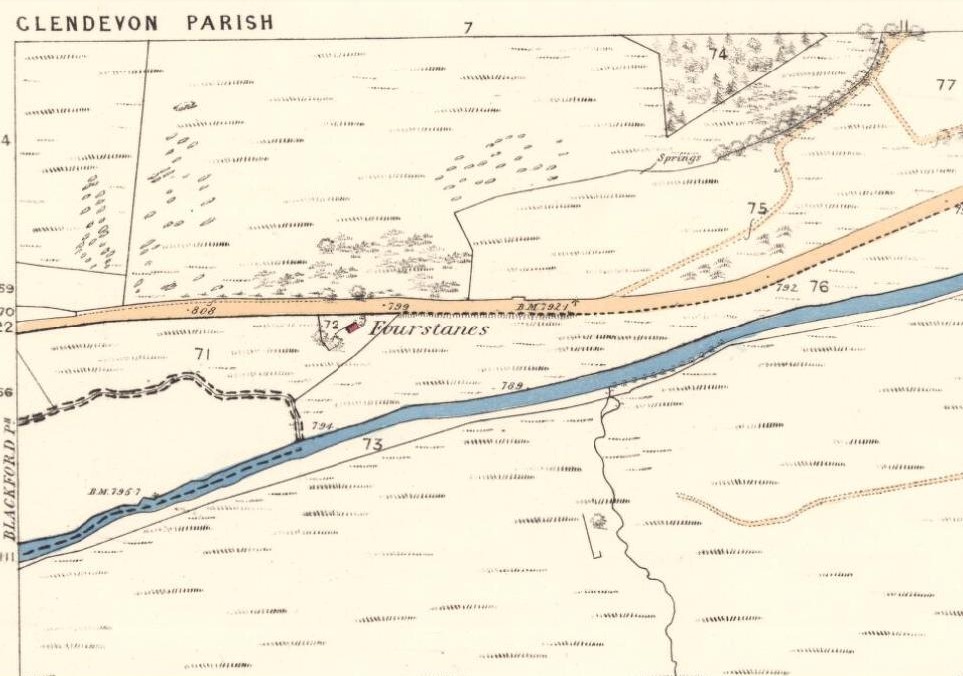

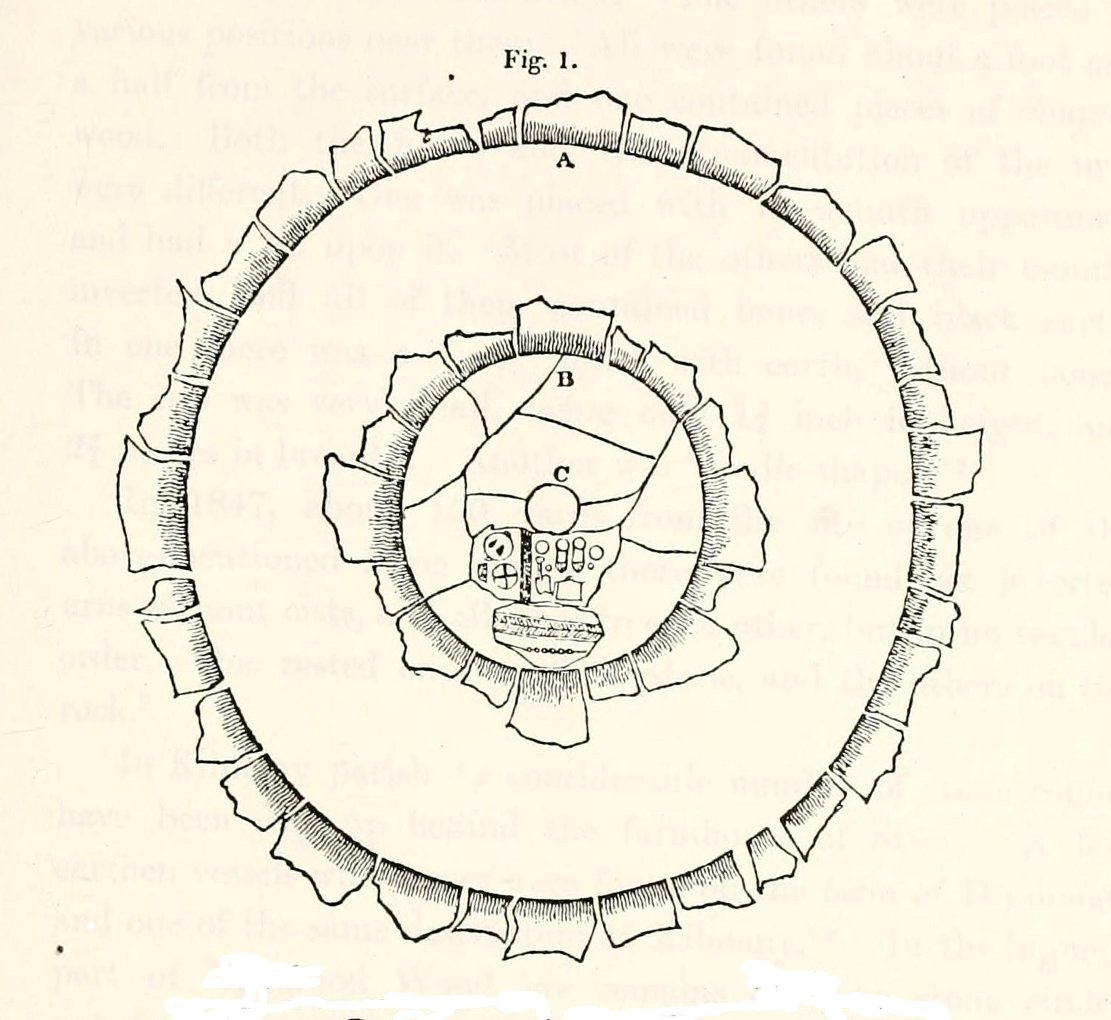

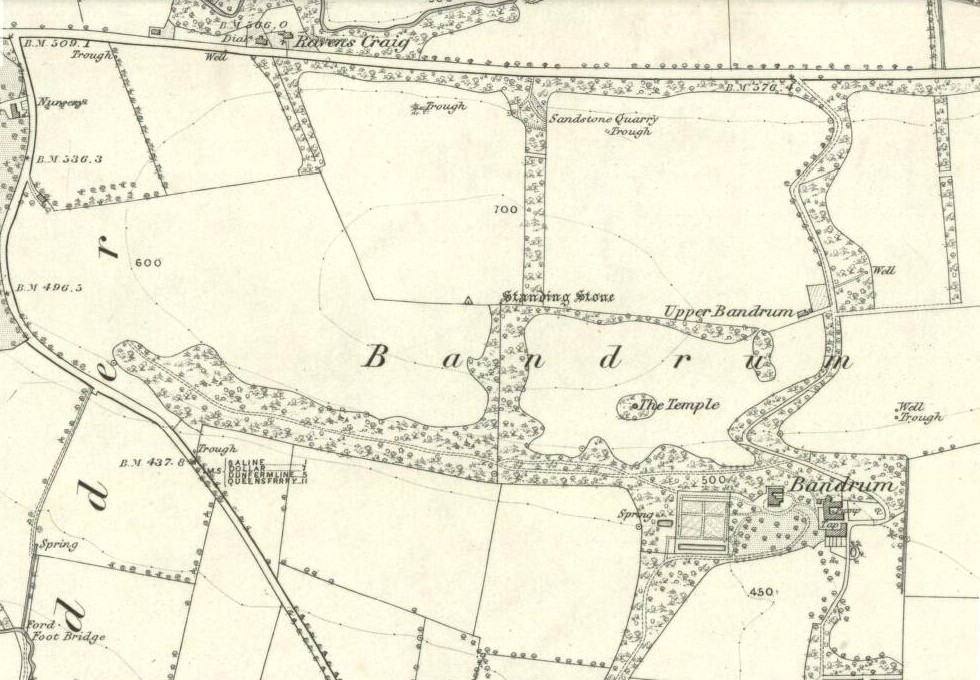

Marked as a singular stone after the Ordnance Survey lads visited here in 1901, early mentions of the site are very scant indeed. In Sir James Simpson’s (1866; 1867) early masterpiece on prehistoric rock art, in which he named the place as the “Circle of Turin,” he related how his friend and associate Dr Wyse told him how this stone “once formed one of a fine circle of boulder stones at Nether Turin,” but said little more. (Simpson was the vice president of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, a professor of medicine, as well as being one of Queen Victoria’s chief physicians.) The “Dr Wyse” in question was very probably Thomas Alexander Wise, M.D., who wrote the little-known but informative and extravagent analysis of prehistoric sites and their folklore in Scotland called A History of Paganism in Caledonia (1884). Therein he told us:

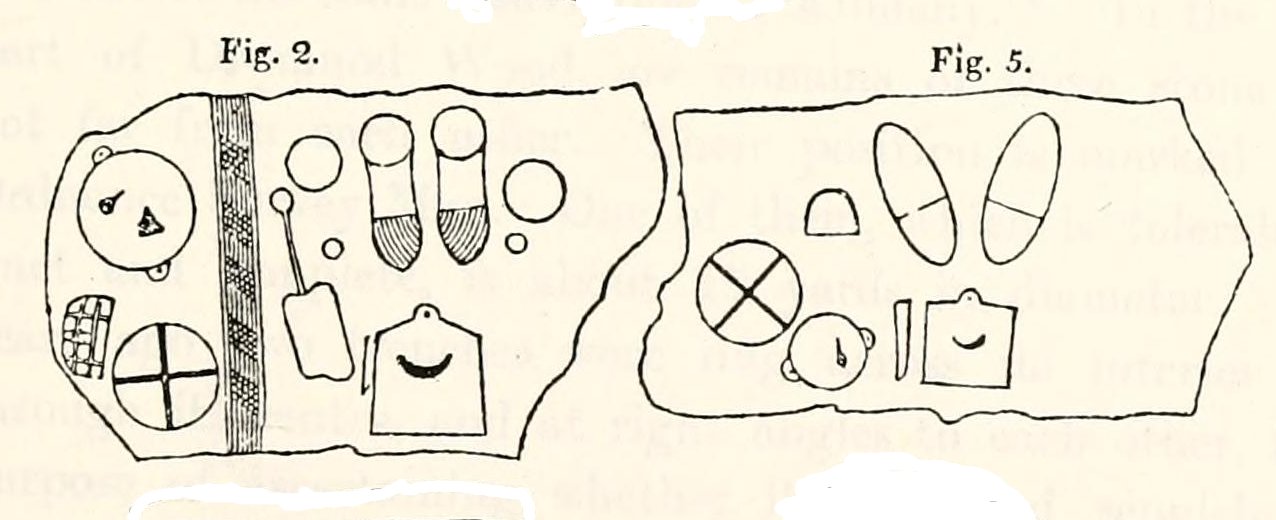

“At Turin, in Forfarshire, there is a large boulder which had formed one of the stones in a circle. On the flat top are several cups arranged irregularly, and without any enclosing circles. This boulder stone is on the NW face of the circle. The other side was towards the SE, facing the rising sun.”

As a result of these early references the site is listed and documented, correctly, as a “stone circle” in Aubrey Burl’s (2000) magnum opus. We do not have the information to hand about who was responsible for the circle’s desctruction—but it was likely done by the usual self-righteous industrialists or christians. It is a puzzle therefore, why Barclay & Halliday (1982) sought to reject an earlier “megalithic ring” status as mentioned by Sir James and Dr Wise, with little more than a flippant dismissal in their short note on the Westerton stone. Unless those two writers can offer vital evidence that can prove that the Westerton standing stone was not part of a megalithic ring, we can of course safely dismiss their unsubstantiated claim.

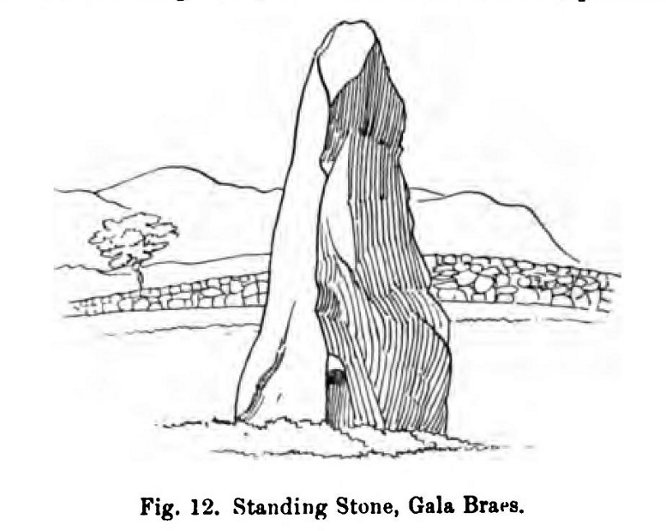

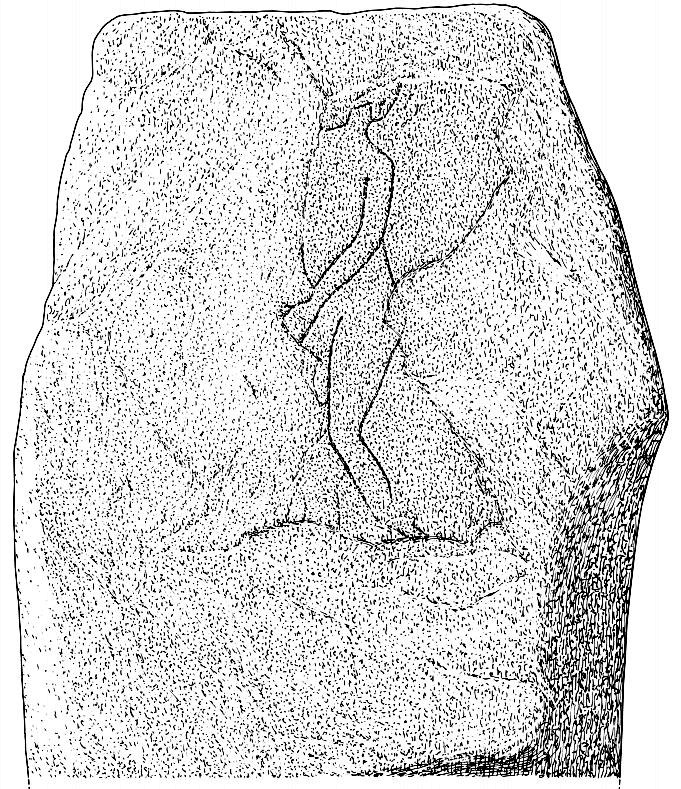

Despite this however, they do give us an intriguing description of a curious carving, faintly visible, of an upright male figure etched onto the west side of this standing stone. The carving has unfortunately been damaged—probably by intruding christians or puritans of some sad form. You’ll see why I’m blaming them in a minute! In their short account of the carving, Barclay & Halliday (1982) state:

“Much of the original surface of the SW face of the stone has scaled off, but, on the surviving portion, there is a part of a human figure…apparently naked, outlined by grooves, measuring between 5mm and 15mm in breadth and up to 7mm in depth. Of the head, only the lower part of the jaw and neck can be identified, and a second groove at the back of the neck probably represents hair or some form of head-covering. The left arm passes across the body into the lap and the arch of the back is shown by a groove which detaches itself from the upper part of the arm. The left leg is bent at the knee and is lost below mid-calf; from mid-calf to jaw is a distance of some 0.85m”

In interpreting this carving the authors make a shallow, if not poor attempt to describe what he may be doing, saying:

“The figure is viewed from its left side and is turned slightly towards the observer. The position of the left arm and leg may be compared with those of a fighting figure depicted on the Shandwick Stone, Easter Ross…but they may also reflect a riding posture; no trace of a mount, however, has survived.”

Well – that is intriguing. But we have to recognise that our authors work for the Royal Commission, which may have effected their eyes and certainly their minds—as everyone else sees something not drawn out of Rorscharch’s famous psychology test! When I put the drawing you can see here (left) onto various internet archaeology group pages (including the Prehistoric Society, etc) the response was virtually unanimous, with some comical variants on what the carved man is doing — i.e., masturbating, or at least committing some sort of sexual act, possibly with another creature where the rock has been hacked away by the vandals. But a sexual act it is! Although such designs are rare in Britain, they are found in prehistoric rock art and later architectural carvings in most cultures on Earth. The nearest and most extravagant examples of such sexual acts can be found in the Scandinavian countries, where fertility images are profuse, often in tandem with typical prehistoric cup-and-ring designs. (see Coles 2005; Gelling & Davidson 1969, etc)

…And, on the very top of the stone, running along its near-horizontal surface, a line of six cup-markings are clearly visible. Intrusions of natural geophysical scars are also there, but the cup-marks are quite distinct from Nature’s wear, all on the west side of the natural cut running along the top. These cup-marks were first mentioned in Simpson’s (1866; 1867) early tome, where he told how his “esteemed friend Dr Wyse discovered ‘several carefully excavated cavities upon its top in groups, without circles.'” Whether these neolithic to Bronze Age elements had any association with the later Pictish-style wanking fella (fertility?) is impossible to know, sadly…

References:

- Barclay, G.J. & Halliday, S.P., “A Rock Carving from Westerton, Angus District,” in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 112, 1982.

- Burl, Aubrey, The Stone Circles of Britain, Ireland and Brittany, Yale University Press 2000.

- Coles, John, Shadows of a Northern Past, Oxbow: Oxford 2005.

- Gelling, Peter & Davidson, Hilda Ellis, The Chariot of the Sun and other Rites and Symbols of the Northern Bronze Age, J.M. Dent: London 1969.

- Sherriff, John R., “Prehistoric Rock Carvings in Angus,” in Tayside & Fife Archaeological Journal, volume 1, 1995.

- Simpson, J.Y., “On Ancient Sculpturings of Cups and Concentric Rings,” in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 6, 1866.

- Simpson, James, Archaic Sculpturings of Cups, Circles, etc., Upon Stones and Rocks in Scotland, England and other Countries, Edmonston & Douglas: Edinburgh 1867.

- Wise, Thomas A., History of Paganism in Caledonia, Trubner: London 1884.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian