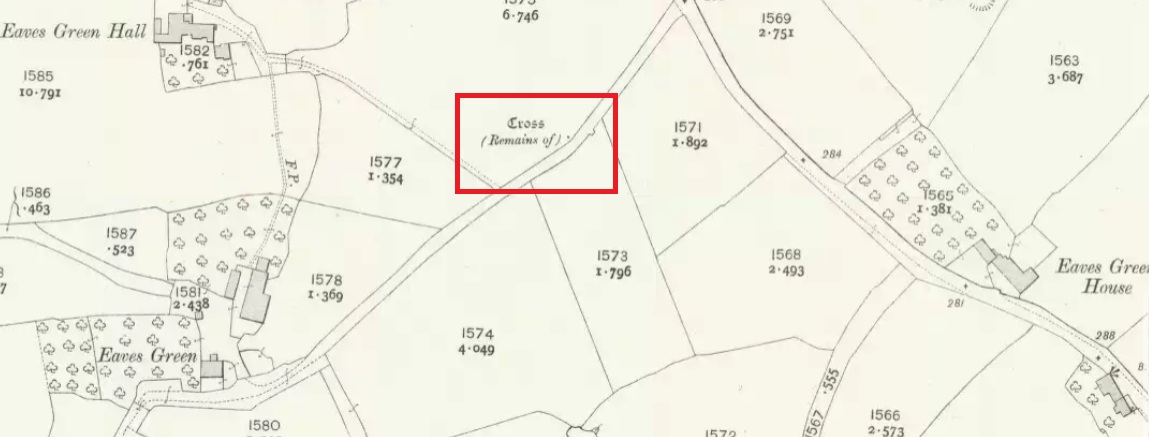

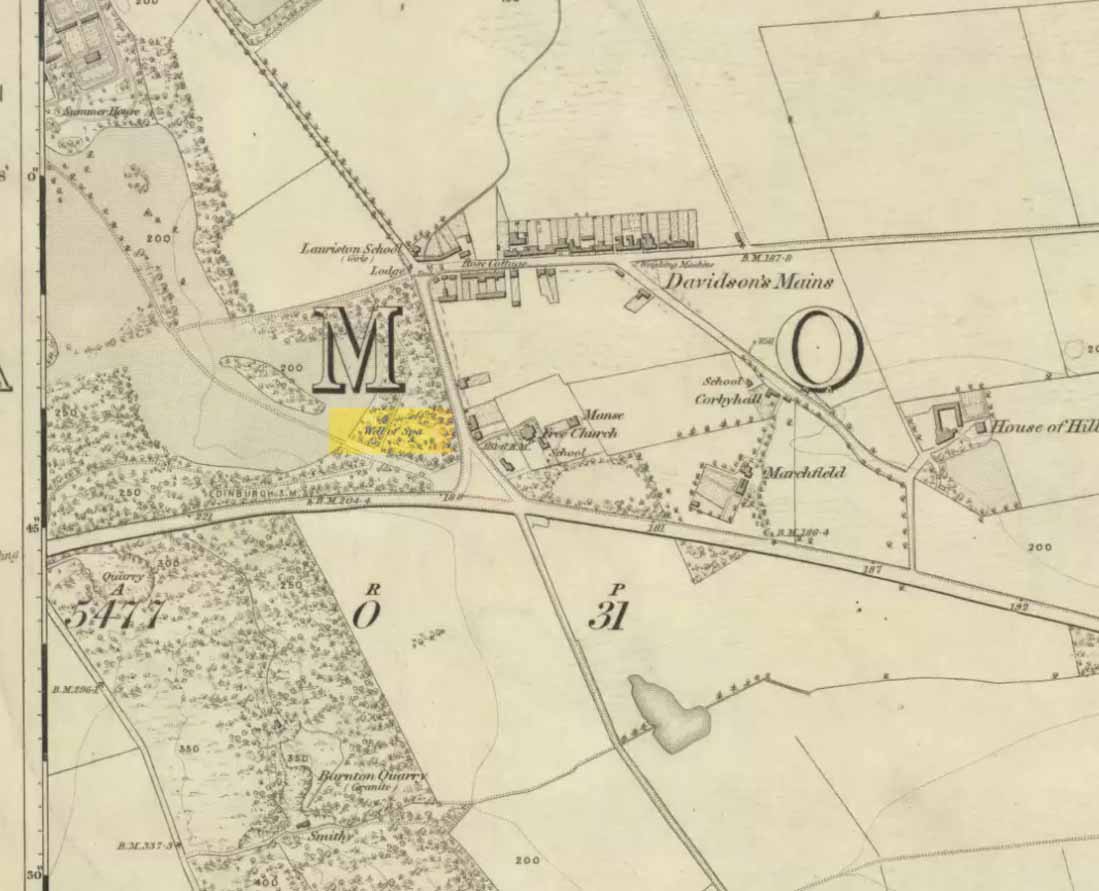

Tomb/s (lost): OS Grid Reference – NS 9928 9865

Archaeology & History

A fascinating site that was described in Johnston & Tullis (2003) local history work on the parish of Muckhart. Amidst an area bedevilled with faerie, boggarts, ghosts and historical shamanic moot sites we find more curious folklore pointing at a long forgotten site, whose age and precise nature remains a mystery. Adjacent to the old boundary line, close to the meeting of streams, the Muckhart authors told that,

“an orchard above the old farmhouse to this day remains mainly untouched. It was the burial site of warlocks from the parish and it is thought some may have even been burned at the Mill. It has always been said that this ground should never be touched! There is an ancient rubble bridge over the Hole Burn which has a Masonic Eye painted on it to ward off any unwelcome spirits. Despite the eye, both the Farmhouse and the Millhouse have been home to many strange and ghostly manifestations.”

The folklore sounds to be a mix of archaic and medieval animistic traits: perhaps of a prehistoric cairn, visited and maintained by local people (as found throughout Britain) until the Burning Times, when christian fanatics arrived, debasing the cultural rites and murdering local innocent people. …Perhaps not.

When Paul, Maggie and I explored the area a few days ago, we were greeted most cordially by the owner of Muckhart Mill, who knew of the folklore, but didn’t know the exact whereabout of the grave. We couldn’t find any clues as to its exact location either. Apart, perhaps, from the top of the hill immediately above the orchard where, alone and fenced off with an old covered (unnamed) well, a solitary Hawthorn tree stood. We each recalled the aged relationship that Hawthorn has in witch-lore… but that’s as far as it went. The grave remains hidden and may have been destroyed. If anyone discovers its whereabouts, please let us know so that a preservation order can be made to ensure its survival.

References:

- Johnston, Tom & Tullis, Ramsay (eds.), Muckhart, Clackmannanshire: An Illustrated History of the Parish, MGAS 2003.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

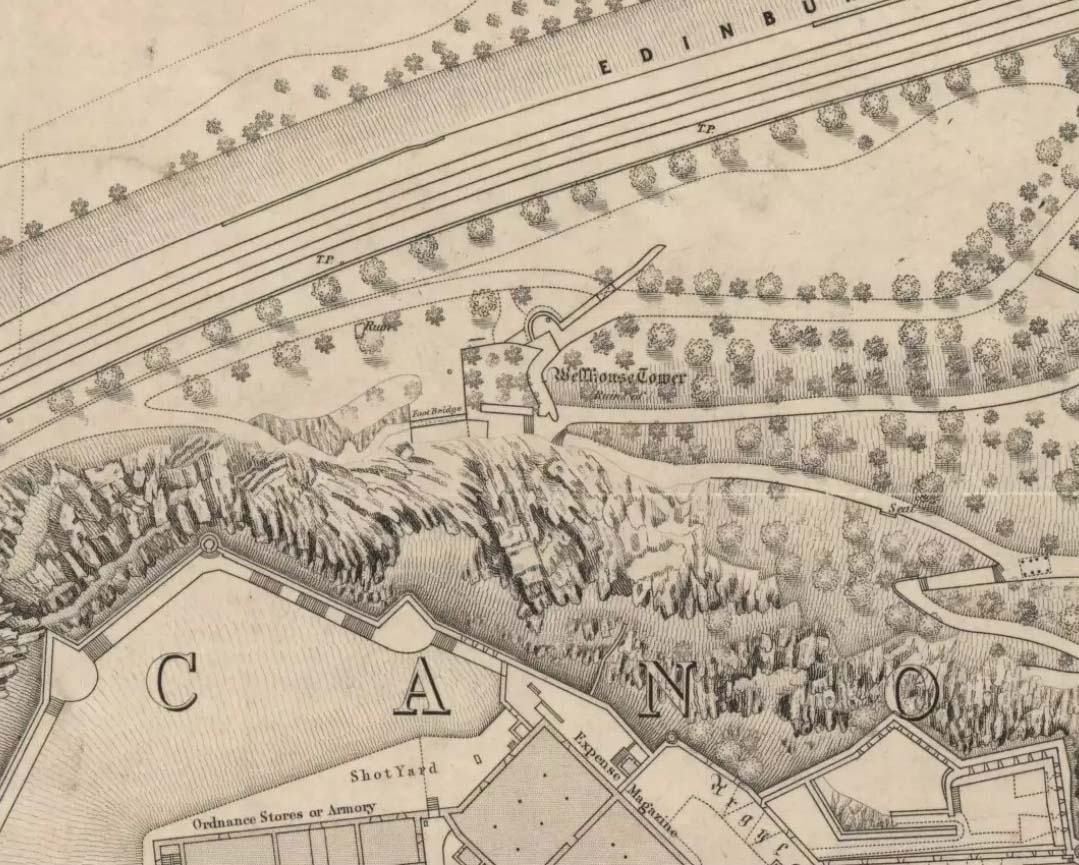

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.