Legendary Tree: OS Grid Reference – TL 5352 2083

Also Known as:

- Doodle Oak

Archaeology & History

Hatfield’s Doodle Oak, 1807

Erroneously ascribed by the reverend Winsland (1952) as being the ‘Doodle Oak’, the ancient and giant tree called the Broad Oak was, as records show, always known by this name, but was subsequently replaced by another after its demise. It was this second tree that became known as the Doodle Oak. Winsland described it as “an immense and famous oak tree”, under whose “spreading branches in olden days the Lord of the Manor probably held his court and dispensed justice.”

The tree was described as early as 1136 AD and was probably an early tribal meeting site, or moot spot. In Philip Morant’s (1763) work, he described it as,

“A tree of extraordinary bigness. There has been another since…called Doodle Oak.”

The old Oak in 1890

The Doodle Oak was thought to date from around 10-11th century and its predecessor may have been upwards of a thousand years old before this one took its place. In 1949, one patient botanist, Maynard Greville, investigated the Doodle Oak tree-rings and found it to be 850 years old. Other estimates suggest it was a hundred years older than that! Whichever was the correct one, a measurement of its trunk found it to be some 19 yards in circumference – one of the largest trees ever recorded in Britain!

Sketches of its dying body were thankfully made near the beginning and the end of the 19th century: one in Mr Vancouver’s (1807) Agriculture of Essex, and the other by Henry Cole of the Essex Naturalist journal.

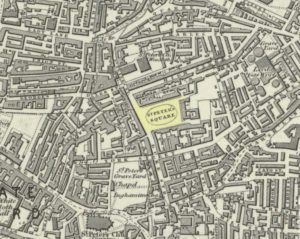

Doodle Oak on 1896 map

Some speculate that the Broad Oak of ancient times and the subsequent Doodle Oak were at very different places in the parish, but without hard evidence this idea is purely hypothetical. And whilst the name ‘broad’ oak is easily explained, the name ‘doodle’ is slightly more troublesome. However, a seemingly likely etymology is found in the Essex dialect word dool, which Edward Gepp (1920) told,

“seems to mean, (1) a landmark; (2) a path between plots in a common field.”

The former of the two would seem to be the most likely. This is echoed to a greater degree in Wright’s (1900) magnum opus, where he found the dialect word dool all over the southeast, meaning,

“a boundary mark in an unenclosed field.”

Giant trees on ancient boundaries, like the Broad Oak of earlier times, would seem to be the most probable reason for its name. Today, all that’s left of the site is a small plaque on a small tree-stump, telling us what once stood here…

References:

- Gepp, Edward, Contributions to an Essex Dialect Dictionary, George Routledge: London 1920.

- Morant, Philip, The History and Antiquities of the County of Essex – volume 2, 1763.

- Reaney, P.H., The Place-Names of Essex, Cambridge University Press 1935.

- Vancouver, Charles, General View of the Agriculture of the County of Essex – volume 2, Richard Phillips: Blackfriars 1807.

- Winsland, Charles, The Church of Saint Mary the Virgin, Hatfield Broad Oak, Anchor: Bishop Stortford 1952.

- Wright, Thomas, English Dialect Dictionary – volume 2, Henry Frowde: London 1900.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.