Stone Circle (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – NS 9909 7387

Also Known as:

Archaeology & History

In an Address to the Scottish Society of Antiquaries in the middle of the 19th century, Sir James Simpson (1862) pointed out the outright destruction and vandalism that incoming land-owners (english mainly, and probably christians too) had inflicted on the monuments of the Scottish people. Stone circles and two cromlechs, he said, that had existed in this part of West Lothian for thousands of years, were recently destroyed when Simpson was alive. One of them was here at Kipps. He told:

“In 1813 the cromlech at Kipps was seen by Sir John Dalzell, still standing upright. In describing it, in the beginning of the last century, Sir Bobert Sibbald states that near this Kipps cromlech was a circle of stones, with a large stone or two in the middle; and he adds, “many such may be seen all over the country.” They have all disappeared; and latterly the stones of the Kipps circle have been themselves removed and broken up, to build, apparently, some neighbouring field-walls, though there was abundance of stones in the vicinity equally well suited for the purpose.”

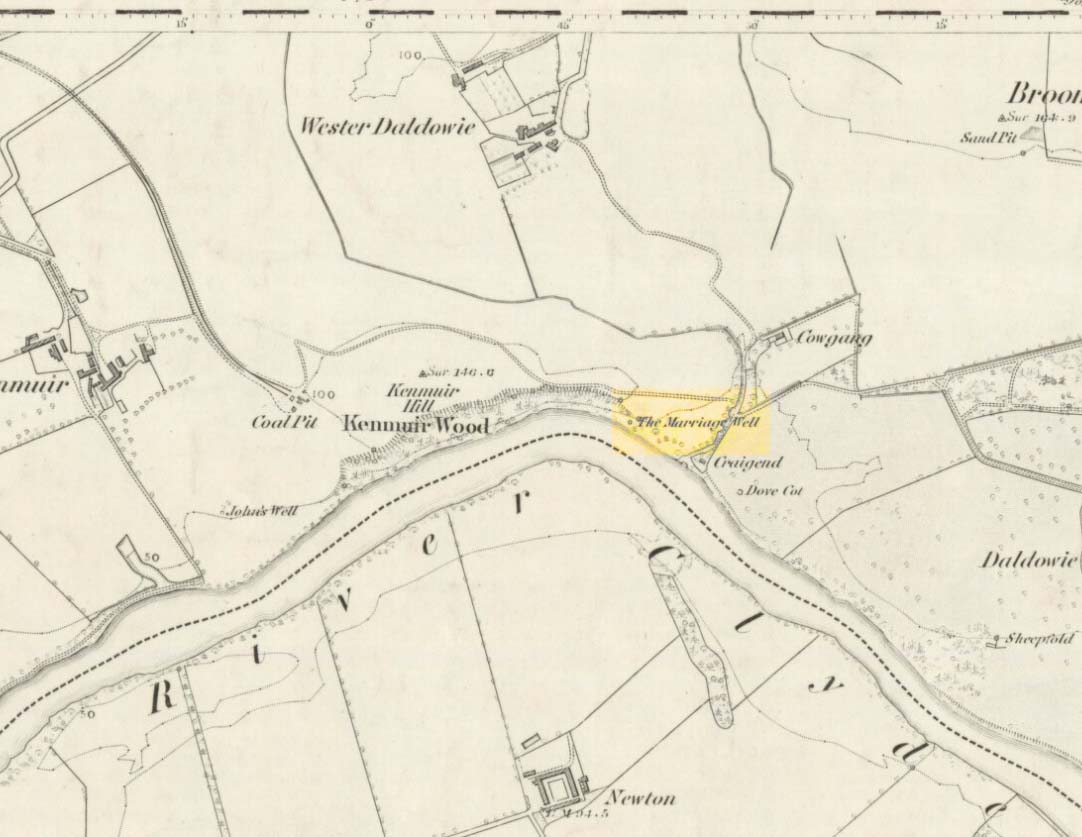

Simpson suggested, quite rightly, that efforts should be made to resurrect the old monument. In his day the fallen remnants of the ‘cromlech’ that had stood inside the circle were still in evidence and it was highlighted on the early OS-map of the region; and when the northern antiquarian Ratcliffe Barnett (1925) came walking here earlier in the 20th century he told he could still see “the remains of an ancient cromlech, which stood within a circle of stones.” Around the same time, the Royal Commission (1929) lads looked for these remains but seemed to have gone to the wrong site, “a quarter-mile northwest of Kipps Farm”, where they nevertheless found,

“a tumbled mass of boulders containing about thirty stones, one being erect; they vary from 6 by 3 by 1½ feet by 4 by 3 by 2½ feet, and are probably the remains of a cairn.”

When the renowned chambered tomb explorer Audrey Henshall (1972) followed up the directions of the Royal Commission, she was sceptical of giving any prehistoric provenance to the rocks there, describing them simply as geological “erratics.”

The very place-names Kipps may derive from the monument, for as Angus MacDonald (1941) told, “the word seems to come from Gaelic caep, ‘a block’”, but the word can also mean “a sharp-pointing hill, a jutting point, or crag on a hill”, and as the house and castle at Kipps is on an outlying spur, this could be its meaning.

Folklore

Local lore told how lads and lassies would use the stones as a site to promise matrimony with each other, by clasping their hands through a gap on the top boulder. Using holes in or between stones to make matrimonial bonds, where the stone is the witness to the ceremony, occurs at many other sites and became outlawed by the incoming christian cult, which took people away from the spirits of rock, waters and land.

References:

- Barnett T. Ratcliffe, Border By-Ways & Lothian Lore, John Grant: Edinburgh 1925.

-

Duns, J., “Notes on a Burial Mound at Torphichen, and an Urn found near the ‘Cromlech’ at Kipps, Linlithgowshire”, in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 12, 1878.

-

Henshall, Audrey S., The Chambered Tombs of Scotland – volume 2, Edinburgh University Press 1972.

-

Lewis, A.L., “The Stone Circles of Scotland,” in Journal Anthropological Society Great Britain, volume 30, 1900.

-

MacDonald, Angus, The Place-Names of West Lothian, Oliver & Boyd: Edinburgh 1941.

-

Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments, Scotland, Midlothian and Westlothian, HMSO: Edinburgh 1929.

-

Simpson, James Y., “Address on Archaeology,” in Proceedings Society of Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 4, 1862.

Acknowledgements: Accreditation of early OS-map usage, reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.