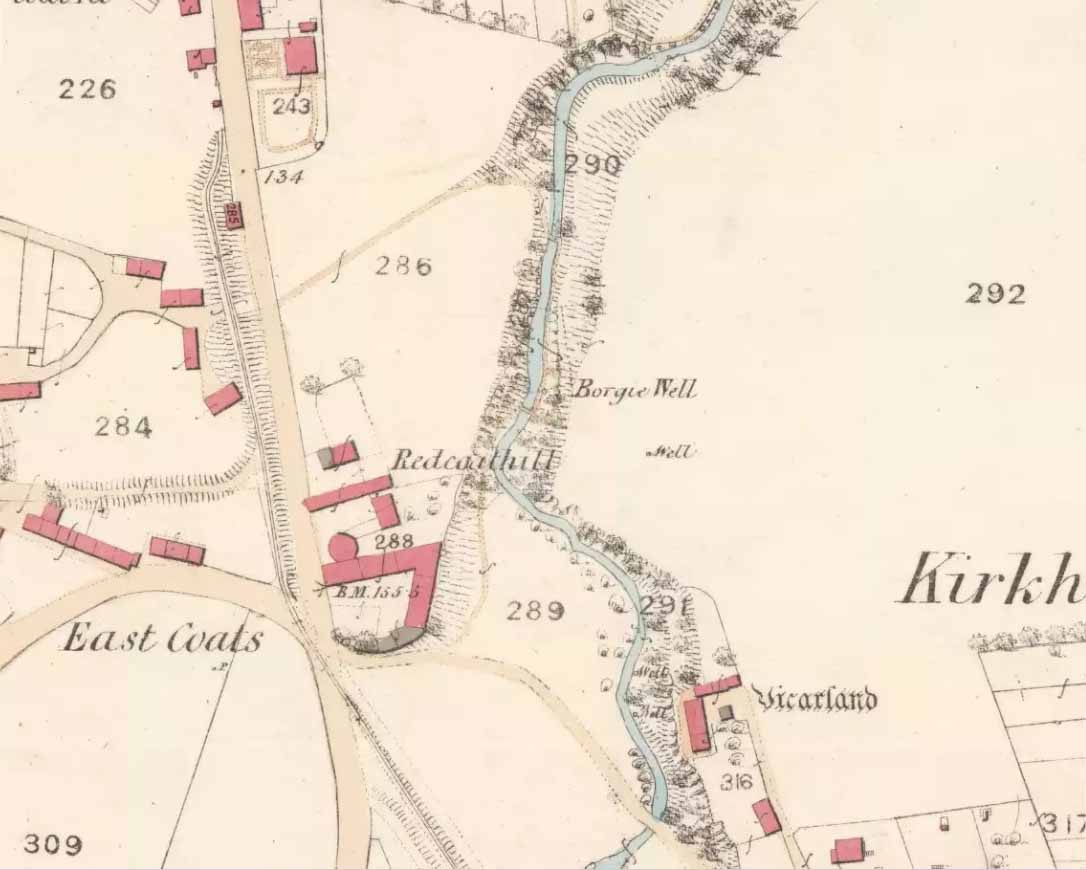

Sacred Well: OS Grid Reference – NS 64412 60194

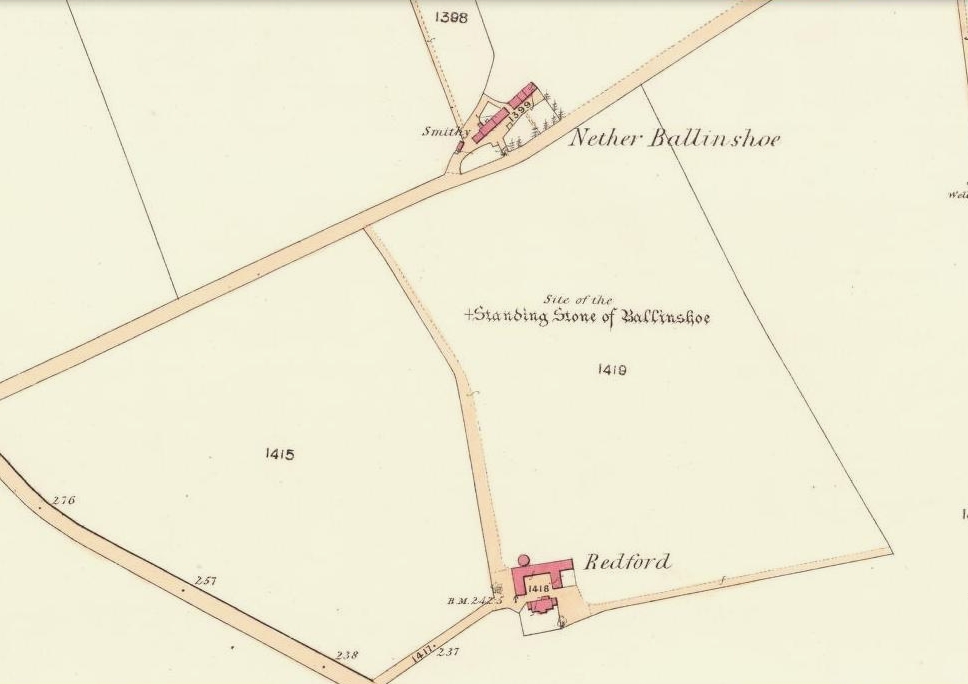

There must be an easier way to visit this site than the method I used. Which was: along Cambuslang’s Main Street (A724), turn up the B759 Greenlees Road for nearly 500 yards, turning left onto Vicarlands Road. Notice the grass verge and steep slope immediately to your left. Walk into the tree-lined gorge, following the left-side along the edges of the fencing. About 150 yards down the steep glen, note the very denuded arc of stone-walling and rickety fencing on the other side of the burn. That’s it! (broken glass and an excess of people’s domestic waste are all the way down; very difficult to reach, to say the least!)

Archaeology & History

Found in a dreadful state down the once-beautiful Borgie Glen, this is one of the most curious entries relating to sacred and healing springs of water anywhere in the British Isles. Indeed, the traditions and folklore told of it seem to make the site unique, thanks to one fascinating factor…..which we’ll get to, shortly…..

The name ‘Borgie’ is an oddity. Local historians J.T.T. Brown (1884) and James Wilson (1925) wondered whether it had Gaelic, Saxon or Norse origins, with Brown thinking it may have been either a multiple of a simple bore-well, or else a title given it by a travelling minister from Borgue, in Kirkcudbright. Mr Wilson took his etymology from the very far north where “there is a stream called the Borgie” (just below the Borgie souterrain). This is said to be Nordic in origin, with

“borg, a fort or shelter, and -ie, a terminal denoting a stream. It is almost certain that our Borgie has the same origin; that is, ‘the fort or shelter by the stream.’”

The Borgie Well was described by a number of authors, each of whom spoke of its renown in the 19th century and earlier. One of my favourite Glasgow writers, Hugh MacDonald (1860), had this to say about the place:

“There are several fine springs in the glen, at which groups of girls from the village, with their water pitchers, are generally congregated, lending an additional charm to the landscape, which is altogether of the most picturesque nature. One of these springs, called “the Borgie well,” is famous for the quality of its water, which, it is jocularly said, has a deteriorating influence on the wits of those who habitually use it. Those who drink of the “Borgie,” we were informed by a gash old fellow who once helped us to a draught of it, are sure to turn “half daft,” and will never leave Cambuslang if they can help it. However this may be, we can assure such of our readers as may venture to taste it that they will find a bicker of it a treat of no ordinary kind, more especially if they have threaded the mazes of the glen, as we have been doing, under the vertical radiance of a July sun.”

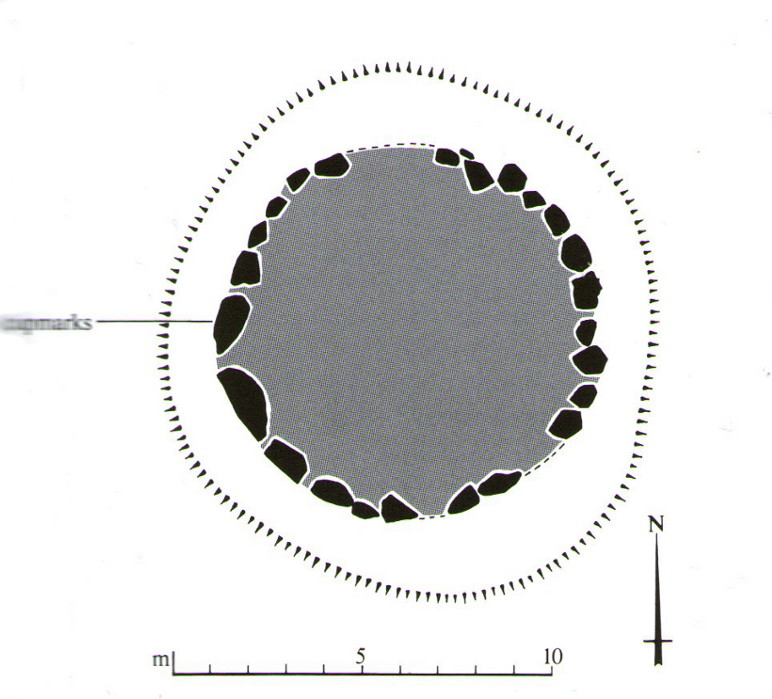

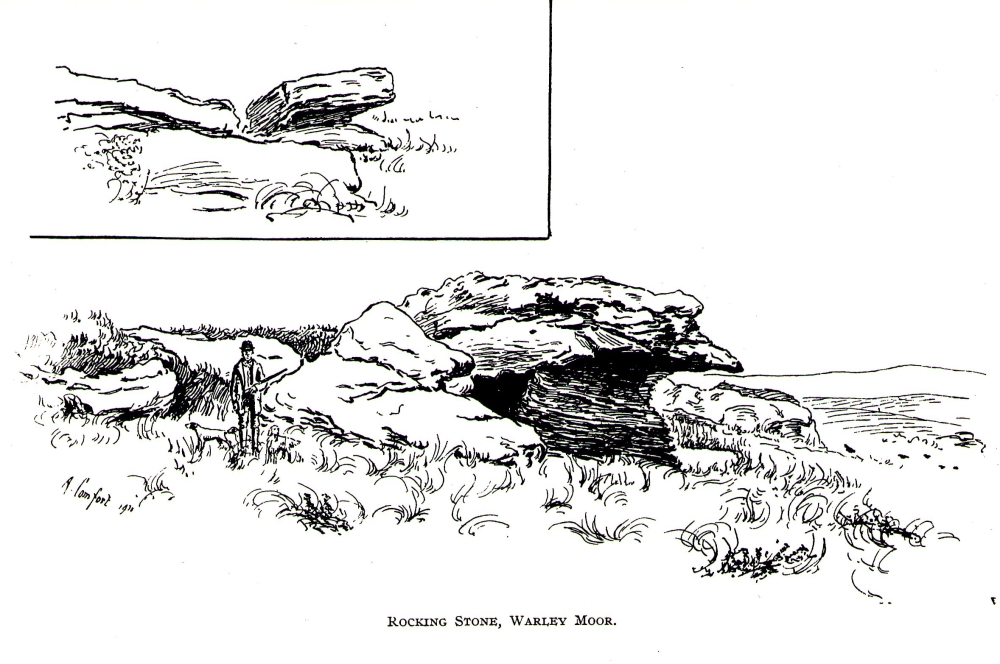

It’s somewhat troublesome to reach, but a beautiful landscape indeed is where, today, only remnants of the Borgie Well exist. A very eroded semi-circle of walling and iron bars protects what was once the waters of the well—which have long since fallen back to Earth. Behind it, right behind it, overhangs the cliff and a small cave: a recess into the Earth with its very own feeling. It has the look and feel of a witch’s or hermit’s den with distinct oracular properties. This geomancy would not have gone unnoticed by our ancestors. In this enclaved silence, the once bubbling waters beneath the cliffs give a feel of ancient genius loci—a memory still there, despite modernity. Whether this crack in the Earth and its pure spring waters was some sort of Delphic Oracle in days gone by, only transpersonal ventures may retrieve… Perhaps…

In the 19th century a path took you into the glen from the north, and a commemorative plaque was erected here by a Dr Muirhead, where now lie ruins. It read:

The Borgie Well here

Ran many a year.Then comes the main verse :_

Wells wane away,

Brief, too, man’s stay,

Our race alone abides.

A s burns purl on

With mirth or moan,

Old Ocean with its tides,

Each longest day

Join hands and say

(Here where once flowed the well)

We hold the grip

Friends don’t let slip

The Bonny Borgie Dell.

1879.At the base was carved an appeal to the local folk:

Boys, guard this well, and guard this stone,

Because, because, both are your own.

The plaque has long since gone; and according to the local historian J.T.T. Brown (1884), the waters went with it due to local mining operations around the same time. But there was an additional rhyme sang of the Borgie Well which thankfully keeps the feel of its memory truly awake (to folk like me anyway!). It is somewhat of a puzzle to interpret. Spoken of from several centuries ago, it thankfully still prevails:

A drink 0′ the Borgie, a taste 0′ the weed,

Sets a’ the Cam’slang folks wrang in the heid.

Meaning simply, if you drink the waters of this well, you’ll get inebriated! It’s the derivation of the word ‘weed’ that is intriguing here. In Grant’s (1975) massive Scottish dialect work we are given several meanings. The most obvious is that the weed in the poem is, literally, a weed as we all know it. But it also means ‘a fever’; also ‘to cut away’ or ‘thin out’; to carry off or remove (especially by death); as well as a shroud or sheet of cloth. These meanings are found echoed, with slight variants, in the english dialect equivalent of Joseph Wright. (1905) Hugh MacDonald told that the Enchanter’s Nightshade (Circaea lutetiana) grew hereby—which, initially, one might think could account for this curious rhyme. But the Enchanter’s Nightshade has nothing to do with the psychoactive Nightshade family, well-known in the shamanistic practices of our forefathers. However, in the old pages of one Folklore Society text, William Black (1883), in repeating the curious rhyme, told us:

“The Borgie well, at Cambuslang, near Glasgow, is credited with making mad those who drink from it; according to the local rhyme —

A drink of the Borgie, a bite of the weed,

Sets a’ the Cam’slang folk wrang in the head.”The weed is the weedy fungi.”

A mushroom no less! In John Bourke’s curious (1891) analysis of early mushroom use, he repeats Mr Black’s derivation. If this ‘weed’ was indeed use of mushrooms that made the local folk “go mad” or “wrang in the head” (and if not – what was it?), it’s an early literary account of magic mushroom intoxication! If this interpretation is correct, the likelihood is that the Borgie Well was a site used for ritual or social use of such intoxicants. Many sites across the world were used by indigenous people for ritual intoxication, and this could be one of the last folk remnants of such usage here. We know that Scotland has its own version of cocaine, used extensively by our ancestors (even the Romans described it) and which was still being used by working Highlanders in the 20th century—but early descriptions of mind-affecting mushrooms are rare indeed!

Mr Black gives no further folklore, nor the source of his information, other than to suggest that the madness incurred by the Well typified the people of Cambuslang! “Weedy fungi” may have been ergot (Claviceps purpurea), but the incidence of the grasses upon which it primarily grows, rye, here seems unlikely—and the folklore would certainly have included the ‘death’ aspects which that fungus brings! Fly agarics (Amanita muscaria) however, may have grown here. Old birches are close by, which produce nice quantities of those beautiful fellas. On the fields above the gorge, where now houses grow, Liberty Caps (Psilocybe semilanceata) may have profused—as they do in the field edges further out of town—but this species has no local cultural history known about from the early period. We must, however, maintain a healthy scepticism about this interpretation—but at the same time we have to take into account the ‘intoxicating’ madness which the combination of the “waters and the weed” elicited.

One final note I have to make before closing this site entry: despite the beautiful location, this small gorge is in a fucking disgraceful state. Some of the people who live in the houses above the gorge should be fucking ashamed of themselves, dumping masses of their household rubbish and tons of broken glass into the glen. If these people are Scottish, WTF are you doing polluting your own landscape like this? This almost forgotten sacred site needs renewing and maintaining as an important part of your ancient heritage. Have you no respect for your own land?!?

References:

- Armitage, Paul, The Ancient and Holy Wells of Glasgow, TNA 2017.

- Black, William George, Folk Medicine: A Chapter in the History of Culture, Folk-lore Society: London 1883.

- Brotchie, T.C.F., “Holy Wells in and Around Glasgow,” in Old Glasgow Club Transactions, volume 4, 1920.

- Brown, J.T.T., Cambuslang, James Maclehose: Glasgow 1884.

- Bourke, John G., Scatalogic Rites of All Nations, W.H. Lowdermilk: Washington 18981.

- Grant, William (ed.), The Scottish National Dictionary – volume 10, SNDA: Edinburgh 1975.

- Hansen, Harold A., The Witches’ Garden, Santa Cruz: Unity 1980.

- MacDonald, Hugh, Rambles round Glasgow, John Cameron: Glasgow 1860.

- MacKinlay, James M., Folklore of Scottish Lochs and Springs, William Hodge: Glasgow 1893.

- Morris, Ruth & Frank, Scottish Healing Wells, Alethea: Sandy 1982.

- Walker, J.R., ‘”Holy Wells” in Scotland”, in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 17, 1883.

- Wilson, James A., A History of Cambuslang, Jackson Wylie 1925.

- Wright, Joseph, The English Dialect Dictionary – volume 6, Henry Frowde: Oxford 1905.

Acknowledgements: Huge thanks again, in various ways, to Nina Harris for getting us here; and Paul Hornby, for reminding me of my literary sources when I needed them! Thanks too to Travis Brodick and his beautiful photo of the Amanita muscaria cluster.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian